"Iron General" Dokhturov. “Iron General” Dokhturov “Smolensk cured me”

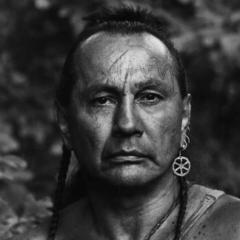

Dokhturov Dmitry Sergeevich

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dokhturov.jpg#/media/File:Dokhturov.jpg

Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov (1759-1816) - Russian military leader, infantry general (1810). During the Patriotic War of 1812, he commanded the 6th Infantry Corps and led the defense of Smolensk from the French. At Borodin he commanded first the center of the Russian army, and then the left wing. From the Tula nobles.

He received his education in the Corps of Pages.

He began his service in 1781 as a lieutenant in the Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment, in 1784 as a captain-lieutenant, in 1788 as a captain.

As part of the guards detachment he participated in the Russian-Swedish war of 1788-1790. In the Battle of Rochensalm he was wounded in the shoulder, but remained in service. Near Vyborg he was wounded a second time. For his distinction he was awarded a golden sword.

In 1795 he was promoted to colonel, on November 2, 1797 to major general, on October 24, 1799 to lieutenant general. On July 22, 1800, he was dismissed and put on trial, but was acquitted and re-entered into service in November. From July 30, 1801, chief of the Olonets Musketeer Regiment, from January 26, 1803, chief of the Moscow Musketeer Regiment and infantry inspector of the Kyiv Inspectorate.

In the campaign of 1805, he took part in the battles of Krems (he was awarded the Order of St. George, 3rd class) and Austerlitz (Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd class). In the campaign of 1806−1807 he distinguished himself at Golymin, Yankov, and was again wounded at Preussisch-Eylau did not leave the battlefield and was awarded a sword with diamonds. He distinguished himself again at Gutstadt and was wounded for the fourth time at Heilsberg, but again remained in service. Under Friedland, he commanded the center and covered the retreat across the Alle River. For this campaign he was awarded the Order of St. Anne 1st class, St. Alexander Nevsky and the Prussian Red Eagle.

On April 19, 1810, he was promoted to general of the infantry and in October led the 6th Infantry Corps.

During Napoleon's invasion in 1812, Dokhturov, stationed in the area of the city of Lida with the 6th Infantry and 3rd Reserve Cavalry Corps, found himself cut off from the main forces of the 1st Army, but with a forced march (60 versts per day) to Oshmyany he was able to break away and reach to connect with them. During the Battle of Smolensk, despite his illness, on the orders of M.B. Barclay de Tolly, he took over the leadership of the city’s defense and for ten hours repelled the fierce attacks of the enemy, leaving the burning Smolensk only around midnight.

In the Battle of Borodino, Dokhturov commanded the center of the Russian army between the Raevsky battery and the village of Gorki, and after Bagration was wounded, the entire left wing. He put the upset troops in order and consolidated his position.

“At the beginning of the battle, he commanded the 6th Corps and held back the enemy’s efforts with his usual firmness; having taken command of the 2nd Army after Prince Bagration, with his orders he overcame all the enemy’s aspirations to attack our left wing, and since his arrival at the place he has not lost a single step of the position he had taken.”

- M.I. Kutuzov. From the description of D.S. Dokhturov in the report presenting a list of generals who distinguished themselves under Borodin.

At the council in Fili on September 1, 1812, he spoke in favor of a new battle near Moscow. In the battle of Tarutino he also commanded the center. In the battle of Maloyaroslavets, Dokhturov held back the strongest pressure of the French for 7 hours (before the approach of Raevsky’s corps), declaring:

“Napoleon wants to break through, but he won’t have time, or he’ll walk over my corpse.”

In total, he held the defense for 36 hours, and forced Napoleon to turn onto the Smolensk road. For this battle he was awarded the Order of St. George, 2nd class.

He distinguished himself in the battle of Dresden and in the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig, led the siege of Magdeburg (late October - mid-November 1813) and Hamburg (January - May 1814). After this he went to Bohemia to treat his wounds. During the 2nd campaign in France (1815) he commanded the right wing of the Russian army.

In January 1816 he retired due to illness. He died in November of the same year. He was buried in the Ascension David Hermitage. Regarding his death, one of his contemporaries wrote:

“For the Obolensky family, yesterday was marked by a sad incident. General Dokhturov, married to the prince’s sister, was present at the wedding, then the next day he had dinner with us and finally yesterday he was at a dinner party at the Obolenskys, playing cards with his mother, then, returning home, he suddenly died at 11 o’clock, while we were all at ball with Apraksina... Imagine that Dokhturov rented a house, and alone, without a family, came to Moscow two weeks ago to set up an apartment, awaiting the arrival of his wife; a bad road detained her in the village. Imagine the grief she will have to learn about! »

General Dokhturov was married to Princess Maria Petrovna Obolenskaya (1771-1852), daughter of Prince Pyotr Alekseevich Obolensky (1742-1822) and Princess Ekaterina Andreevna Vyazemskaya (1741-1811). She was the sister of Princes Vasily and Alexander Obolensky. Born in marriage:

Catherine (1803-1878), maid of honor.

Varvara, died a girl.

Peter (1806-1843), a retired captain, was married to Agafya Alexandrovna Stolypina (1809-1874); their son Dmitry Petrovich Dokhturov is a lieutenant general, a participant in the wars with the highlanders and the Turks.

Sergei (1809-1851), memoirist, owner of the Polivanovo estate near Moscow. He was married to the stepdaughter of Count A.I. Gudovich, Countess Ernestina Manteuffel.

Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov remained in people’s memory as “a knight without fear and reproach.” The fame of the “iron general” was assigned to him: he was wounded four times, but never left the battlefield. He was not distinguished by any special outstanding fighting qualities, but his tenacity, perseverance, and fortitude made him one of the favorite generals among soldiers and officers.

Two golden swords

Future hero of the War of 1812 D.S. Dorokhov received baptism of fire in 1789 - during the war between Russia and Sweden. On August 13, he first participated in the battle on the island of Kutsal-Mulin and received his first wound. A bullet hit him in the shoulder, but three days later he was again in battle during the capture of a Swedish battery, and on August 21 he took part in the landing on the island of Gevanland. Catherine II drew attention to this young officer and, having learned about his bravery, personally presented him with a golden sword with the inscription “For bravery.”

At the end of May 1790, during the capture of the island of Kargesira, the cannonball was torn out of Dorokhov’s hand and crushed the sword granted to him. Catherine II, having learned about what had happened, decided to replace the lost sword with another. Since then, Dokhturov took with him this imperial gift, so valuable to him, on all his military campaigns.

“Here the honor is my wife, and the people entrusted to me are my children.”

In the campaign of 1805, Dokhturov commanded one of the columns of the army led by M.I. Kutuzov. He had to fight with such prominent Napoleon's military leaders as Mortier and Dupont. In the battle of Krems, Dokhturov, despite the dangerous situation, repelled the attacks of Mortier on one side and Dupont on the other. In difficult mountain conditions, without artillery, Dokhturov walked along the slopes of the Bohemian Mountains and attacked the French from the rear. The French army could not withstand the Russian attack and was forced to retreat, and Mortier himself was almost captured. For his contribution to the victory at Krems, Dokhturov, who had previously had no insignia, received the Order of St. George, 3rd degree, and stood on a par with such heroes of the war of 1805 as Miloradovich and Bagration.

In the Battle of Austerlitz, Dokhturov was able to show his persistent character and dedication to the cause. When the Russian troops and their allies were retreating, with his composure he managed to prevent the panic that began among the soldiers and until the very end he led the crossing of the small Litava River. The following conversation is often cited as evidence of his heroism:

Someone close to him advised him to take care of himself. “Remember that you have a wife and children!” - they told him. “Here the honor is my wife, and the people entrusted to me are my children,” he objected.

His courage this time did not go unnoticed. Alexander I awarded Dokhturov the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd degree. A M.I. Kutuzov wrote about this: “I am firmly convinced in my soul that it is awarded to one of the distinguished generals, who especially deserved the attention of His Imperial Majesty, the love and respect of the entire army.”

The troops loved this general, and he invariably remained a friend of the soldiers and officers, saw them as his own family and took care of them as much as he could. The soldiers trusted him, and he knew how to inspire them and strengthen their spirit at the right moment: “Brothers! be sure that on every cannonball, on every flying bullet it is written who will be wounded or killed! You yourself saw that Sidorov hid behind the ranks, but did not escape death - he was killed! Death that overtakes a warrior is a shameful death! It’s nice to die where honor and duty appoint a place!”

“Smolensk cured me”

Portrait of Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov by George Dow

Dokhturov began the War of 1812 as part of Barclay de Tolly's 1st Western Army. On July 17, Barclay de Tolly sent Dokhturov to Smolensk to defend the city. By July 19, Dokhturov arrived in Smolensk, but the difficult road undermined his health, and Dmitry Sergeevich began to develop a fever. He was very weak when Napoleon approached Smolensk. Barclay de Tolly asked Dokhturov whether his health would allow him to take over the defense of Smolensk. “Brothers,” he answered, “if I die, it is better to die on the field of honor than ingloriously on the bed!” His corps was reinforced by the divisions of Neverovsky, Konovnitsyn and the Jaeger Brigade of General Palitsyn.

All Napoleon's attacks were repulsed. But soon a fire started: the city burned. In a few hours, the French and Russians lost several thousand people, several generals died. At midnight Dokhturov received orders to retreat and leave Smolensk. He managed to withdraw his troops from the city in excellent order and in a very organized manner, which was noticed even by the French who entered the city. Many have noticed that Dokhturov’s health has improved significantly. “Yes,” he answered, “Smolensk cured me.”

Borodino: “Stay to the last extreme”

In the Battle of Borodino, Dokhturov, on the orders of Kutuzov, replaced the mortally wounded Bagration as commander of the 2nd Army. F. Glinka, a participant in the Battle of Borodino, recalled: “Into the fire and confusion of the left wing rode a man on a tired horse, in a worn general’s uniform, with stars on his chest, of small stature, but tightly built, with a purely Russian physiognomy. He showed no outbursts of brilliant courage, in the midst of death and horror, surrounded by the family of his adjutants, he rode calmly, like a good landowner between working villagers; with the care of a practical man, he looked for meaning in the bloody confusion of the local battle. It was D.S. Dokhturov."

In the midst of the battle, Dokhturov received a note from Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov: “Stay to the last extreme.” Meanwhile, a horse was killed under him and another was wounded. He calmly drove around the positions, giving instructions, directing fire, encouraging the soldiers. In the evening, when the battle died down, Kutuzov greeted the brave general with the words: “Let me hug you, hero!”

"Napoleon will walk over my corpse"

Dokhturov was one of those who opposed leaving Moscow without a fight: he believed that a general battle should be fought right near Moscow. However, he naturally obeyed Kutuzov’s order. On this occasion he wrote to his wife: “Thank God, I am completely healthy, but I am in despair that they are leaving Moscow. Horrible! We are already on this side of the capital. I am making every effort to convince him to meet the enemy halfway; Bennigsen was of the same opinion, he did what he could to assure that the only way not to give up the capital would be to meet the enemy and fight with him. But this courageous opinion could not influence these cowardly people: we retreated through the city. What a shame for the Russians to leave their homeland without the slightest rifle shot and without a fight. I'm furious, but what can I do? We must submit, because God’s punishment seems to be looming over us. I can’t think otherwise: without losing the battle, we retreated to this place without the slightest resistance. What a disgrace!"

Already during the counter-offensive of the Russian army, Dokhturov heroically showed himself in the battle of Maloyaroslavets. “Napoleon wants to break through,” said Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov, “but he won’t have time or will walk over my corpse.” With the support of Raevsky's corps, Dokhturov fought all day for Maloyaroslavets. The city changed hands eight times, but the French were never able to advance. For his feat at Maloyaroslavets, Dokhturov was awarded the Order of St. George, 2nd degree.

Upon returning to Russia on January 1, 1816, Dokhturov was dismissed from service for health reasons with the right to wear a uniform and a full pension. His colleagues expressed sincere gratitude and regret as they saw him off in retirement. The generals and officers of the 3rd Infantry Corps presented him with a snuff box with a picture of the Battle of Maloyaroslavl and the inscription:

“The Third Corps, which served with honor and glory under your command in the famous year 1812. war, presents you as a sign of gratitude with a snuff box depicting your feat at Maloyaroslavets and asks you to accept it as a monument of gratitude.”

| Tweet |

Chronicle of the day: French troops are preparing to leave Moscow

French troops in Moscow began to prepare to leave the city. At this point, Napoleon’s plan was as follows: to leave a small garrison in Moscow under the command of Mortier, and move the main forces to the Tarutino camp. After defeating or driving back the Russian army, occupy Kaluga with its food warehouses, and then retreat to Yelnya and further to Smolensk. On this day, Napoleon even considered the possibility of occupying Tula and destroying the Tula arms factory. Napoleon shared these considerations with Yu.B. Mare.

Person: Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov

Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov (1756-1816)

Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov was born into a family of small landed nobles in the Tula province with strong military traditions: his father and grandfather were officers of the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment, the oldest regiment of the Russian Guard, formed by Peter I. In 1771, he began his training in the Corps of Pages. And in 1781 he was enlisted in the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment with the rank of lieutenant. In 1784, he was noticed by G. Potemkin and appointed by him company commander. Dokhturov took part in the Russian-Swedish war of 1788-1790. He was wounded twice and for his distinction was awarded a gold sword with the inscription “For bravery.” After the end of the war, Dmitry Sergeevich transferred from the guard to the army. In 1795, with the rank of colonel, he headed the Yelets musketeer regiment, and two years later, for the excellent training of the regiment, he was promoted to major general by Emperor Paul I. Since 1803, with the rank of lieutenant general, he was the chief of the Moscow infantry regiment.

Dokhturov fought against Napoleon in the campaign of 1805. He proved himself brilliantly in the battles of Krems and Austerlitz. For the courage shown in the battle of Austerlitz, Dokhturov received the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd degree.

With the beginning of the Russian-Prussian-French war of 1806-1807. Dokhturov's division operated under Golymin and Yankov. In the battle of Preussisch-Eylau, Dokhturov was wounded, but refused to leave the battlefield, for which he was awarded a golden weapon for the second time. Then he distinguished himself in the battles of Gutstadt and Heilsberg, and was again wounded. In the battle of Friedland, he commanded the center and covered the retreat of Russian-Prussian troops across the Alle River. For this military campaign he was awarded the Order of St. Anne 1st class, St. Alexander Nevsky and the Prussian Order of the Red Eagle. In October 1809, Dokhturov was appointed commander of the 6th Infantry Regiment. And in 1810 he received the rank of general from the infantry.

During the Patriotic War of 1812, Infantry General Dokhturov was the commander of the 6th Corps as part of Barclay de Tolly's 1st Army. He heroically fought with the Napoleonic army near Smolensk and Borodino. During a counterattack by the Russian army, he led his troops into battle at Tarutino, near Maloyaroslavets.

During the campaign of 1813, Dokhturov took part in the battle of Dresden and in the four-day Battle of the Peoples near Leipzig, and then, until the Russians captured Paris, he was in the troops blockading Hamburg.

In 1816, Dokhturov was forced to retire due to illness. He spent the last months of his life in Moscow. On November 14, 1816, Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov passed away. The hero of the war of 1812 was buried in the monastery of David's Hermitages in the Serpukhov district of the Moscow province.

September 29 (October 11), 1812

Battle for Vereya

Person: Rustam Raza

Armenians in the War of 1812

September 28 (October 10), 1812

September 28 (October 10), 1812

Third Western Army advances

Person: Egor Andreevich Agte

South direction. Actions of the Third Western Army

September 27 (October 9), 1812

Russians attack at Likhoseltsi

Person: Nikolai Ivanovich Grech

Magazine "Son of the Fatherland"

September 26 (October 8), 1812

The French are exporting looted valuables

Person: Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky (1783-1852)

Russian bard

September 25 (October 7), 1812

Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov

...And Dokhturov, the storm of enemies,

A reliable leader to victory!

V. A. Zhukovsky

Little is known about the childhood years of the outstanding Russian commander, hero of the Patriotic War of 1812. Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov was born on September 1, 1759 in the family of Sergei Petrovich Dokhturov, captain of the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment. His family was ancient, known in history since the 16th century, but very poor. The Dokhturovs were ordinary middle-class small-scale nobles.

Military traditions were honored in the family. Dmitry's father and grandfather were officers of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the oldest regiment of the Russian Guard, formed by Peter I in 1687 in the village of Preobrazhenskoye. Dmitry Dokhturov spent his childhood on his mother’s estate in the village of Krutoy, Kashira district, Tula province. It was an even, measured life, normal for a very ordinary manor’s estate, not marked by anything particularly remarkable.

Dmitry’s most vivid impressions came from communicating with peasants and yard children. He subtly noticed the peculiarities of the Russian character, the kindness and cordiality of ordinary people. And perhaps it is precisely from these childhood impressions that the constant concern for the Russian soldier that he always showed after becoming a military leader comes from.

Dmitry's parents, however, despite their very modest incomes, sought to give their children a good education at home. Particular attention was paid to the study of foreign languages. At the age of eleven, Dmitry Dokhturov easily spoke French and German, and even Italian, which was not so popular at that time.

The arrangement of Dmitry's future was the main concern of his parents. The financial condition of the family did not allow one to count on an easy and brilliant career. There could only be hope for military service. In addition, from an early age the future commander showed interest in his father’s war stories. In January 1771, Sergei Petrovich took his son to St. Petersburg, where the old Preobrazhensky had to use his connections. He turned to influential colleagues in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, and the boy was introduced to Catherine II.

On February 1, 1771, Dmitry was admitted to the Corps of Pages. Pupils of the Corps of Pages studied French and German, geometry, geography, fortification and history, and also learned the art of dancing, drawing, fencing and horse riding.

Unlike many, Dmitry Dokhturov could only rely on himself in everything, so he was distinguished by his diligence and diligence. In 1777 he became a chamber page, and in the spring of 1781 he left the Corps of Pages with the rank of lieutenant of the guard.

Service in the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment, where Dokhturov was assigned upon graduation, began quite happily. Back in 1774, Catherine II appointed Adjutant General G. A. Potemkin with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel of the Guard as commander of the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Potemkin quickly discerned Dokhturov’s military abilities and appreciated his knowledge and diligence. Dokhturov was promoted to captain and soon began to command a company.

G. A. Potemkin was not only a courtier, but also a prominent military leader. He did not like empty parades and paid considerable attention to the training of troops, which he tried to build in accordance with the requirements of the Rumyantsev-Suvorov military school. He changed the clothes of the troops. At his suggestion, their braids were cut and the soldiers stopped powdering themselves. In a special memo, Potemkin wrote: “Curling, powdering, braiding hair - is this a soldier’s job? They don't have valets. Why farts? Everyone must agree that it is healthier to wash and comb your hair than to burden it with powder, lard, flour, hairpins, and braids. A soldier’s toilet should be such that it’s up and ready.” In addition to limiting punishments for soldiers, prohibiting the use of soldiers for private work of commanders and other minor innovations, Potemkin also made military reforms. He increased the cavalry by 18 percent, forming 10 squadron dragoons and 6 squadron hussars. To strengthen the infantry, he increased the number of grenadiers, formed four-battalion musketeer regiments, and organized jäger battalions. He also introduced the Jaeger battalion into the Preobrazhensky Regiment. It included selected soldiers and the best officers. Among others, Dokhturov was awarded this honor. In 1784, he was appointed commander of a Jaeger company.

Most of the Preobrazhentsy's time was spent in garrison service - guarding the royal court, maintaining city and regimental guards, participating in parades and ceremonies. In addition to direct official duties, guard officers were required to be “indispensable participants in all palace balls, masquerades, kurtags and assemblies, as well as operas that were given in the Highest presence, in a house specially built for this purpose on the Nevsky prospect.” During the reign of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, such holidays occurred almost every day. The historian of the Preobrazhensky Regiment writes about the life of guard officers in somewhat condensed colors: “As for the life of guard officers in St. Petersburg in the age of Catherine, the whole society, in the last years of her reign, was drowning in luxury, and the former cheapness was completely forgotten. Traders and shopkeepers did not know the limits of the prices they set for customers, seeing changes in fashions and styles almost monthly. By this time, from any decent person, and especially from a guard officer, what was required, first of all, was “an elegant appearance and clothes with a hairstyle,” so that the poorest of the Preobrazhents considered it his absolute duty to order several uniforms a year, costing him at least 120 rubles each . Unfortunately, during this period we have to note a certain decline in discipline and laxity in the performance of official duties. Given the complete indifference to such a sad state on the part of the authorities, it is not surprising that this debauchery increased every day. It got to the point that guard officers could often be seen on the street, freely walking around at home, that is, in dressing gowns, and their wives put on a uniform and performed the duties of a husband. The revelry and debauchery of the guards youth began to take on colossal proportions. There was no end to the stories about broken windows, about merchants scared half to death by the guards, etc.”

Dmitry Dokhturov was not satisfied with such service; he longed for real work, worthy of a Russian officer. Thus passed several years of service, which did not bring Dokhturov either rank or fame.

In June 1788, the Swedes began military operations against Russia. However, the Swedish offensive was suspended, and only in the summer of 1789 the Russian army itself intensified its actions. A war at sea was imminent.

Captain Dokhturov, at the head of a company, arrived in Kronstadt in May 1789, where a rowing flotilla of rangers from the guards regiments was being formed. Here, until July, the guards were trained in naval combat. In July, 18 galleys of the rowing flotilla, together with the Baltic Fleet, came out to meet the Swedes.

The Swedes did not want to fight on the open sea and stood in the Rochensalm roadstead. However, this did not stop the Russian squadron, and on August 13, 1789, a fierce battle took place, which lasted 14 hours. The guards showed an example of high courage and bravery. To block the entry of the Russian fleet, the Swedes sank several of their ships. For four hours, under fire from a Swedish frigate and Swedish coastal batteries, the Guards used boats to cut a passage for their ships using axes and hooks. The galleys also followed the small ships. Hand-to-hand combat ensued.

The commander of the Russian squadron, Prince Nassau-Siegen, wrote in a report to the empress: “We could not have achieved such a complete victory over them if we had not managed to open a passage that was captured by the gunboats armed with the Life Guards. The commander of the galley fleet cannot sufficiently praise this corps in general; but those who were on the kaikas and gunboats, according to him, exceed everything that he can say to praise them ... "

Captain Dokhturov also distinguished himself in this battle. The soldiers were amazed at the courage of their seemingly plain-looking, average-sized, always calm commander. But his swiftness and composure during boarding battles were worthy of a seasoned soldier. In the heat of battle, he did not even pay attention to his shoulder wound and participated in the battle to the end. Dokhturov’s actions did not go unnoticed. His reward was a golden sword with the inscription “For bravery,” which, besides him, was awarded to only one officer for this battle, captain Stepan Mitusov.

Dokhturov also distinguished himself in the Swedish campaign of the following 1790 during the landing on the island of Gerland, where he commanded three hundred Preobrazhensky soldiers.

The Swedish fleet, having suffered a series of defeats, retreated to the Vyborg Bay, where it was pinned down by Russian ships.

On June 21, Gustav III tried to escape the trap into which he had led his fleet. The battle lasted two days, and success fluctuated first in one direction and then in the other. This is where the evasive light vessels of the rowing flotilla of the guards were needed. They managed to enter from the rear and ensured the victory of the Russian fleet.

After the end of the Swedish campaign, the guard returned to St. Petersburg, and for Dmitry Dokhturov, ordinary garrison service and the life of a guard officer began again. Such service did not satisfy Dokhturov, who dreamed not of court and high society balls, but only of the benefit of the Fatherland. Dokhturov decides to transfer to serve in the field army. His request was granted, and Dokhturov, with the rank of colonel, became commander of the Yelets musketeer regiment. Later, Dokhturov will say: “I have never been a courtier, I have not sought favors in the main apartments or from the courtiers - I value the love of the troops, which are priceless to me.”

By 1805, when Russia found itself in a state of war with Napoleon, Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov was with the rank of lieutenant general and headed the Moscow Musketeer Regiment, which, as part of the Podolsk Army, was to set out on the Austrian Campaign.

The Russian army at this time was in many ways inferior to Napoleon's army. Of course, there were talented generals, such as Suvorov’s heroes Bagration and Miloradovich, and there were also many soldiers who participated in Suvorov’s Italian and Swiss campaigns. However, Pavlov's innovations caused lasting damage to the army. The training of the army was based on the “Military Regulations on Field Infantry Service” approved by Paul (1796), in which the main attention was paid to drill training, and the main form of combat was stated to be outdated by that time and refuted by the military practice of Rumyantsev and especially Suvorov. tactics. After ascending the throne, Alexander I made some minor changes in the army, but in general the decrees of Paul I remained almost untouched.

In the Podolsk army with a total strength of 50 thousand people there were many experienced soldiers who fought in Suvorov’s troops, but the army’s weapons needed updating. Leading generals came to the conclusion that it was necessary to introduce new battle tactics in the army, taking into account the experience of Suvorov’s campaigns and battles. But there was no time to retrain the soldiers and rebuild the army, and everything was done in a hurry, during the campaign.

The army left Radziwillow, where it was formed, on August 13, 1805, and on September 9 it was led by M. I. Kutuzov. The march to Austria was carried out in two parts. The infantry was ahead, consisting of five detachments, commanded by Major General P. I. Bagration, Major General M. A. Miloradovich, Lieutenant General D. S. Dokhturov, Major General S. Ya. Repninsky and Lieutenant General L. F. Maltits. The infantry was followed by cavalry and artillery.

The hike took place in the most difficult conditions. The roads were washed away by the autumn rains. It was necessary to make daytime stops to give the troops a rest and at least somehow put their clothes and shoes in order. The soldiers cooked their food over fires.

Dokhturov, like other generals, had to devote a lot of time to providing food for his troops, since the army was poorly supplied with provisions. But Dokhturov directed the main forces to train soldiers in loose formation, shooting, and hand-to-hand combat. In this, he received considerable assistance not only from experienced officers, but also from Suvorov veterans who trained newcomers. These lessons will not be in vain, for which the soldiers will subsequently be especially grateful to their commander.

Russian troops were marching to join the allied Austrian army of 46,000 under the command of General Mack. But by the time Kutuzov was already nearby, Makk's troops surrendered without a fight. This happened on October 7, 1805 near the town of Ulm. On the same day, Kutuzov approved the plan for a possible general battle, which he had outlined several days earlier. Already here Kutuzov showed great confidence in Dokhturov. He prescribed: “During the case against the enemy, if all the infantry acts together, then senior lieutenant general Dokhturov will command both flanks.” However, Kutuzov managed to avoid a general battle with many times superior French forces. A systematic retreat began from Braunau to Krems, which lasted about a month. The soldiers were hungry and naked. But no one expected help from the allied army. “We walk at night, we have turned black... officers and soldiers barefoot, without bread. What a misfortune to be in an alliance with such scoundrels, but what to do!..” Dokhturov was indignant in a letter to his wife.

The retreat was carried out along the right bank of the Danube, along a coastal strip 200–300 meters wide, framed on the left by the Danube and on the right by wooded mountains. The rearguard was commanded by Bagration and so successfully that the French were never able to inflict any significant damage on our army.

Napoleon sent Mortier's corps ahead to enter Krems before the Russians and block their path across the Danube. Having learned about the movement of Mortier's corps towards Krems, Kutuzov accelerated the pace, and Russian troops crossed the bridge when Mortier had just approached Krems.

Kutuzov saw that Mortier's corps was in a very disadvantageous position. He sent Dokhturov with his divisions to the rear and flank of Mortier's corps, and Miloradovich was supposed to launch a blow from the front. Dokhturov led his troops through a steep wooded slope, left the brigade of Major General A.P. Urusov in the mountains so that he would block Mortier’s retreat through the mountains, and he himself with the remaining regiments went to the rear of the French. The 6th Jaeger Regiment rushed into a bayonet attack, the French could not stand it and retreated to the village of Loim, where they took up a convenient position. Then Mortier launched a cavalry counterattack against Dokhturov and managed to stop the offensive.

Dokhturov sent the brigade of Major General K. K. Ulanius to bypass the enemy and attack him from the flank at the time when the Moscow regiment began to advance from the front. It was already dark Dokhturov himself led the Moscow regiment into the attack. Ulanius struck at the rear and flank at the same time. Panic arose among the French troops. Some units tried to escape through the mountains, but here Major General Urusov blocked their path. Miloradovich's regiments completed the operation. Marshal Mortier himself barely managed to be one of the few to cross the Danube.

Dokhturov reported on this battle to Kutuzov: “All three battalions of the Moscow Musketeer Regiment, which made up the first line, marched forward with their chests, carrying out my orders to the fullest accuracy... The enemy was overturned by the fearless advance of the line, and two of his cannons were overturned by the grenadier battalion of the Moscow Musketeer Regiment under the command of Major Shamshev taken..." According to Dokhturov, "up to two thousand staff and chief officers and lower ranks were taken." In addition, two French banners were captured. In this battle, Dokhturov managed to show himself not only as an executor of the commander’s will and a fearless warrior, but also as a perspicacious military leader who knew how to think strategically.

Here Napoleon realized that although he had a small army in front of him, it consisted of courageous and fearless soldiers, commanded by talented commanders. Despite Napoleon's efforts to force a general battle on the Russians, Kutuzov still managed to unite with Buxhoeveden's corps and change the balance of forces in his favor.

By this time, Alexander I and the Austrian Emperor Franz had arrived in the army. Alexander I thirsted for the glory of conquering Napoleon, and the allied forces, starting on November 15, began to look for battle. Napoleon withdrew his troops, looking for a position convenient for battle. This position soon became the field of Austerlitz.

On November 19, late at night, a hasty military council of the allied forces took place in Krizhanowice, at which the Austrian Colonel Weyrother familiarized the military leaders with the disposition of the battle. The plan was ineffective in every way. However, it was pointless to discuss the plan adopted by both emperors. Kutuzov was only formally listed as commander-in-chief, but in fact, Alexander I took over the leadership of the battle. One of the most bitter pages in the history of the Russian army was approaching. According to the plan, the battle was to begin with the left flank in order to break through and enter the enemy’s rear from the right flank.

On November 20, 1805, at 7 o’clock in the morning, Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov was the first to lead his column on the offensive. Kutuzov wrote about how it developed in a report to Alexander I: “...The first column, having descended from the mountain and passed the village of Augest at about 8 o'clock in the morning, after a stubborn battle forced the enemy to retreat to the village of Telnits... The first column captured the village of Telnits and the defiles... The retreating The enemy troops, having formed up again and received reinforcements, again rushed towards the first column, but were completely overturned, so that this column, observing in everything the disposition given to it, did not cease to pursue the enemy, who had been defeated three times.”

Dokhturov occupied the village of Sokolnitsy and could have continued the offensive, but according to the plan it was necessary to wait for the front to level off. Further events, due to the fault of Alexander I, developed in such a way that Napoleon broke through the center of the allied forces and began to successfully advance in the direction of the village of Augest. True, even before the French completely broke through the center of the Allied forces, there was an opportunity to somehow change the course of events. To do this, Buxhoeveden needed to turn his columns in time to the flank of Soult’s troops, but Buxhoeveden did not heed either Dokhturov’s advice, or even the order to withdraw the troops back given by Kutuzov. Instead, he blindly followed the original disposition and meter by meter led the troops into encirclement. When the French rushed to the rear of the left flank, Buxhoeveden, seeing the complete hopelessness of the situation, abandoned his troops and shamefully fled from the battlefield. The troops of the left flank were led out of encirclement by Dokhturov.

Dokhturov allocated three regiments against Davout’s corps, and with the rest moved to break through. It was possible to escape only through a narrow dam, which was in the hands of the French. Drawing a golden sword with the inscription “For bravery,” Dokhturov shouted: “Guys, here is Mother Catherine’s sword! Behind me!" This was a call to veterans who remembered the victories of the Russian army under Catherine II, it was a reminder of Suvorov’s campaigns. As at Krems, Dokhturov himself led the Moscow regiment into the attack. The French were crushed, a gap formed in their troops, into which Dokhturov’s regiments rushed. But the troops passed through the dam under French artillery fire, and the losses were significant. The shelves put up for cover were almost completely destroyed. 6,359 people died in Dokhturov’s column, that is, more than half of the entire composition. The total losses of the allied forces in the Battle of Austerlitz were 27 thousand people, of which 21 thousand were Russians. Napoleon lost only 12 thousand.

When the next day Dokhturov’s column caught up with the Russian army, it was already considered dead. The repeated “Hurray!”, which spontaneously swept through the army, was the best praise for the courage of the soldiers and the leadership talent of Dokhturov. The name of Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov passed from mouth to mouth. The commander's talent and courage became known not only to Russia, but also to Europe. After Austerlitz, Kutuzov notes Dokhturov as “one of the most excellent generals, especially deserving of the love and respect of the army.” Dokhturov himself wrote to his wife that he “earned something truly very precious in this campaign - the reputation of an honest man.” Contemporaries invariably noted modesty among the qualities of his character, and in this self-esteem it manifests itself in abundance. Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov believed that honest service to the Fatherland naturally presupposes courage and dedication, and that the main concern of a military leader is his armies. So he did, not thinking of the possibility of doing anything else. After the Austrian campaign of 1805, D.S. Dokhturov stood on a par with such military leaders as Bagration and Miloradovich.

However, talented Russian commanders were not particularly honored by the emperor. Kutuzov was sent as the military governor of Kyiv. In 1806, when Russia was supposed to help Prussia in its fight against Napoleon, the Russian army again needed a commander in chief. The tsar did not want to hear about Kutuzov, shifting the shame of Austerlitz onto him. The names of Tatishchev, Knorring, the French General Moreau, who lived in exile in America, and a number of other minor figures began to appear as candidates. Foreigners especially attracted the attention of Alexander, and just as he entrusted the fate of the Russian army at Austerlitz to a mediocre Austrian colonel, so now he was ready to entrust it to some Moreau. Finally, the choice fell on the elderly Catherine General Count M.F. Kamensky, who lived out his life on his estate in the Oryol province.

Field Marshal Kamensky received unlimited powers and went to the army. The Russian army was supposed to unite with the Prussian army, but this did not happen. Even before they united, Napoleon defeated the Prussians near Jena and Auerstedt, occupied Berlin, and soon his troops were already in Poland.

Lieutenant General Dokhturov's division was located near the village of Golymin, 80 kilometers north of Warsaw, when Dokhturov received two packages with instructions. In one, Kamensky reported that he, the commander-in-chief, had transferred his powers to Buxhoeveden, indicating at the same time that instead of the battle of Pułtusk, as previously planned, it was necessary to withdraw troops to the Russian border. Another package was from the commander of the first corps, Bennigsen, who invited Dokhturov to join him and give Napoleon a general battle. Centralized command of the troops was virtually lost. To enter under the leadership of Buxhoeveden was obvious absurdity.

Dokhturov understood that the elderly Field Marshal Kamensky was unsuitable for the role of commander-in-chief, but the appointment of Buxhoeveden, who shamefully abandoned his soldiers in the swamps of Austerlitz, as commander-in-chief, outraged him to the core. Bennigsen invited Buxhoeveden and Essen I, who commanded the corps, to take part in the general battle, but did not find support from them.

Meanwhile, Napoleon mistook the disorderly and devoid of any logic movements of the Russian troops, which stemmed from Kamensky’s contradictory and sometimes mutually canceling orders, for some special trick that he was unable to understand. Deciding that the main Russian forces were in the area of the village of Golymin, Napoleon moved his main formations there. Here, in fact, were Dokhturov’s division, a division under the command of D. B. Golitsyn, and several cavalry regiments.

On December 14, 1806, they had to withstand the onslaught of the corps of Augereau, Davout, Soult, as well as the guard and cavalry. However, the French achieved nothing. The divisions of Dokhturov and Golitsyn formed into a battalion-by-battalion square and met the cavalry with bayonets. Long flintlock rifles (183 cm with bayonet) made Russian infantry invulnerable. Seeing the failures of his cavalry, Napoleon sends infantry into a bayonet attack. As S. G. Volkonsky testifies in “Notes of the Decembrist,” Dokhturov’s grenadiers were offended: “These runts are unworthy of our bayonets!” - they exclaimed and met the French with rifle butts.

However, in the evening Dokhturov and Golitsyn were forced to retreat. During the retreat, they had to fight at night in a street battle, but Dokhturov and Golitsyn still managed to maintain their battle formation. All this day, troops under the command of Bennigsen also held back the attacks of Marshal Lannes' corps. In fact, five Russian divisions held the entire French army for a whole day.

In January 1807, fighting began again. By January 27, the Russian army occupied a position stretching about 3.5 kilometers along the front northeast of Preussisch-Eylau. Dokhturov's division was located in the center opposite Augereau's corps and Murat's cavalry. On January 27, the French launched a series of attacks, in one of which Dokhturov was wounded in the leg by a cannonball fragment. The Russians successfully repelled the attacks of the French, but were unable to consolidate their success, since the army did not have a reserve, which should have been provided by the army commander Bennigsen. As a result, the battle, which lasted more than 12 hours, came to nothing. On the French side, the losses were 30 thousand killed and wounded, on ours - 26 thousand people. At this point hostilities ceased, and for three months both armies prepared for future battles.

In May 1807, the fighting of the opposing armies intensified. Napoleon had up to 200 thousand people, the Russian army under the command of Bennigsen had about 105 thousand. Bennigsen decided to defeat Ney's corps, which had moved forward to the Gutstadt area.

On May 23, Dokhturov's divisions launched an offensive. On May 24, Dokhturov captured the Lomiten crossing and cut off Ney. Bagration successfully attacked from the front, but many Russian units were late for the battle, and it was not possible to fully implement the plan to defeat Ney. Napoleon connected the main forces, and the Russian troops retreated to Heilsberg, where on May 29 they stood against an enemy twice their size for the whole day.

At Heilsberg, Dokhturov received a fourth wound, but, as always, did not leave the battle.

On June 2, 1807, at Friedland, the French managed to force a battle in a position unfavorable for the Russian army. They managed to break Bagration's defenses and pressed the center and right flank of the Russian troops to the river. Lannes and Mortier's corps acted against Dokhturov's two divisions, which occupied the center of Russian positions. It was possible to save the divisions only by urgently organizing a crossing. But there was not a single bridge here. It was necessary to look for a ford in order to ensure the withdrawal of troops through it as quickly as possible, since they would inevitably have to cross under the fire of French artillery. How important it was to find a good ford is proven by the fact that Dokhturov himself went to look for it. He crossed the Alla River on horseback four times until he found a suitable ford. The troops, one might say, crossed safely, but Dmitry Sergeevich himself was one of the last to leave the shore, despite the persuasion of the officers not to put himself at risk.

In this battle, the Russians lost 15 thousand people. This major defeat of the Russian army was at the same time the only one in 1806–1807, which occurred largely through the fault of the army commander. The defeat made such a strong impression that Alexander I considered it best to enter into negotiations with Napoleon, and on June 27, 1807, the Peace of Tilsit was signed.

For the withdrawal of Russian troops at Friedland, Dokhturov was awarded the Order of Alexander Nevsky.

The actions of Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov could serve as a worthy example to any general. It seems that there was no battle in which Dokhturov did not prove himself an experienced and courageous military leader, and in a number of them he provided invaluable benefits to the Russian army. Dokhturov's exploits were awarded. He received orders for Krems, Austerlitz, Golymin, Friedland. For the battle of Preussisch-Eylau he was awarded a sword with diamonds.

But the fate of Dokhturov as a commander took shape in some special way. There are commanders who distinguished themselves in brilliant victories, in daring marches, in victorious battles. Dokhturov showed himself most clearly where the Russian army was in a difficult situation, sometimes on the verge of extermination, as was the case under Austerlitz and Friedland. Saving armies, however, is worth any victory. It is difficult to overestimate the significance of Dokhturov’s activities for the Austrian campaign and for the French campaign of 1806–1807.

Unfortunately, not all of his contemporaries were able to appreciate the merits of Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov. Thus, A.P. Ermolov, comparing Dokhturov with Bagration, notes: “The coldness and indifference to danger characteristic of this general did not, however, replace Bagration. It was not so often that Dokhturov led his troops to victories, it was not in those wars that surprised the universe with the glory of our weapons that he became famous, it was not on the fields of Italy, not under the banners of the immortal Suvorov that he established himself in martial virtues.” The wars were, of course, not the same, and the glory was not the same, but probably only the armies he saved could weigh his merits. Bagration himself, the complete opposite of Dokhturov in character, however, appreciated the military leadership talent of Dmitry Sergeevich and loved him as a person. The friendship between Bagration and Dokhturov surprised many contemporaries and comrades of the commanders.

Soon after the end of the war with Napoleon, Dokhturov received a long sick leave, due to which he did not have to participate in the Russian-Swedish war of 1808–1809. Dmitry Sergeevich spent more than a year in Moscow with his family, enjoying a quiet family life. Sometimes his comrades visited him, a relative, General A.F. Shcherbatov, visited him, and P.I. Bagration also visited. Having recovered his health, Dokhturov began to think about returning to the army.

In the summer of 1809, Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov took command of the 6th Corps.

At this time, the Russian army was being reorganized, and rearmament was partially taking place. Dokhturov threw himself headlong into this work. The following year, 1810, Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov was awarded the rank of infantry general.

From the very beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812, Dokhturov’s corps, which occupied the left wing of the 1st Army, stood a hundred miles south of Vilna and was actually cut off from the main forces of the army. Army commander Barclay de Tolly ordered the corps to be withdrawn to the Drissa camp, where it was planned to fight a general battle. It was necessary to cover a distance of 500 kilometers in difficult conditions. Dokhturov's corps had a hard time - Nansouty's cavalry corps rushed to its rear. To break away from him, Dokhturov’s regiments, despite the impassability and incessant rain, made 50 kilometers a day. The position of Dokhturov's corps was such that it could well have been destroyed, and Napoleon knew this well. It seems that here for the first time Napoleon tried to explain his failures by the Russian climate. An official report published to Europe at the time gave this description: “For thirty-six hours it rained in torrential rain; the excessive heat turned into piercing cold; from this sudden change several thousand horses died and many cannons got stuck in the mud. This terrible storm, which tired out the men and horses, saved Dokhturov’s corps, which alternately encountered the columns of Bordesoul, Soult, Pajol and Nansouty.”

On June 29, Dokhturov’s corps linked up with Barclay’s army. Dokhturov found the positions of the camp to be very unfortunate. He considered it necessary to leave the camp and move to join Bagration’s army. At the military council, opinions were divided: the emperor adhered to Fuhl's plan, according to which a general battle had to be fought here. However, experienced military leaders did not support the emperor’s opinion, and Alexander considered it best to leave the army.

On July 22, the armies of Barclay and Bagration united near Smolensk. At the military council convened by Barclay, it was discovered that the leaders of both armies had differing opinions about further actions. Bagration, Ermolov, Dokhturov and other generals believed that it was possible to take advantage of the scattered nature of Napoleon’s troops and give battle to individual corps of his army. To concentrate troops, Napoleon needed at least three to four days. But Barclay de Tolly did not show decisiveness, and time was lost.

The military council spoke in favor of an offensive, and Barclay was forced to concede. However, he did not dare to fight a general battle and only pushed Platov’s detachment and Neverovsky’s division forward. Two days later, Napoleon concentrated up to 180 thousand people near Smolensk and decided to bypass the Russian army from the rear, so that the Russians would be forced to accept a general battle. However, during a roundabout march, the French came across Neverovsky’s detachment at Krasny, which held the French army for a whole day, allowing Barclay to pull all his forces to Smolensk. Barclay gave the order to retreat along the Moscow road. The battle near Smolensk was fought by Napoleon's 7th Corps of Raevsky and the 27th Division of Neverovsky. They held Napoleon back all day on the fourth of August. Barclay decided to appoint Dokhturov's corps for the defense of Smolensk. Dokhturov was ill, and Barclay sent to ask Dokhturov whether he was able to act in the defense of Smolensk. To this Dmitry Sergeevich replied: “It is better to die on the field of honor than on the bed.” On August 5, Dokhturov's 6th Infantry Corps and Konovnitsyn's 3rd Infantry Division replaced Raevsky's corps and Neverovsky's division.

The resistance shown by Dokhturov was unprecedented; all French attacks were repulsed. Smolensk was burning, there were ruins everywhere, but the city’s defenders did not think of giving up. Only when it became known that Barclay’s army was out of harm’s way, Dokhturov left Smolensk and retreated to the east, destroying the bridge across the Dnieper behind him.

In the Russian army, the question of a single commander-in-chief arose. Barclay de Tolly, although he was Minister of War, commanded only the 1st Western Army. The disagreements that arose with Bagration exacerbated the general dissatisfaction with Barclay’s actions in the army. The majority of patriotic Russian generals wanted to see a commander-in-chief of Russian origin, who would fight not only as a professional, but also as a patriot. Weyrother's mediocre plan, which resulted in the Austerlitz disaster, the flight of Buxhoeveden, and the defeat at Friedland under the command of Bennigsen were still fresh in memory. True, Barclay de Tolly himself was not a mercenary, he began his service from the lower ranks, and was born in Russia. But nevertheless, Barclay’s entourage somehow turned out to be too many foreigners, so that the thought of treason involuntarily arose in the army. Indignant at Barclay’s actions, Bagration wrote to the Tsar that “the entire main apartment is filled with Germans so that it is impossible for a Russian to live and there is no point in it.”

On August 5, the day when Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov led the defense of Smolensk, the Emergency Committee met in St. Petersburg to discuss the candidacy of the commander-in-chief.

Kutuzov, appointed commander-in-chief, arrived to the troops on August 21, and immediately gave the order to concentrate in the area of the village of Borodino.

According to the disposition, the 6th Infantry Corps of Dokhturov and the 3rd Reserve Cavalry Corps of Kreutz formed the center of the Russian troops. Moreover, one of the two advanced detachments of the center was commanded by the legendary N.V. Vuich, Suvorov’s favorite, hero of Izmail, Preussisch-Eylau and Friedland, and later of Borodin, Maloyaroslavets and Leipzig. Overall command of the right flank and center was exercised by Barclay de Tolly, the left flank was under the command of Bagration.

Bagration's severe wound and the impossibility of his further participation in the battle was a significant loss for the army. Konovnitsyn took over temporary command of the left wing. He managed to organize a defense and delay the French advance at the Semenovsky ravine. However, there were not enough forces for counterattacks, and Konovnitsyn withdrew his troops behind the Semenovsky ravine.

Kutuzov sends the Prince of Württemberg to the left flank, but immediately sends an order to the infantry general D.S. Dokhturov: “Although the Prince of Württemberg went to the left flank, despite the fact that you have command of the entire left wing of our army, and the Prince of Württemberg is subordinate to you. I recommend that you hold out until I receive a command to retreat.”

The French carried out the first attack on the village of Semenovskaya with the forces of Ney’s corps and Friant’s division. But Russian artillery stopped the French. At this time D.S. Dokhturov arrived. In his notes, Fyodor Glinka, a participant in the Battle of Borodino, wrote: “Dokhturov, courageously repelling the dangers and encouraging his soldiers with his example, said: “Moscow is behind us!” Everyone should die, but not a step back!“ Death, which met him at almost every step, increased his zeal. Under him, two horses were killed and one was wounded..."

Kutuzov was not mistaken in appointing Dokhturov to command the left flank, and no matter how hot it was here, the French were unable to break through it. This is a considerable merit of Dmitry Sergeevich Dokhturov, who over many years of service has become accustomed to being in the most difficult areas. It must be said that the Dokhturov school was not in vain for his corps. Under Borodin, many officers and privates of his divisions distinguished themselves. The commander of the 24th Infantry Division, Pyotr Gavrilovich Likhachev, who defended Raevsky’s battery after I.F. Paskevich, became especially famous. Dokhturov knew this general well from his participation in the battles of Rochensalm and Vyborg. “Taking advantage of the fact that the 11th and 23rd infantry divisions were busy repelling cavalry attacks,” writes historian of the Patriotic War of 1812 L. G. Beskrovny, “the French infantry rushed to the battery. The enemy forces were four times greater than those of the 24th Infantry Division defending the battery. The Russians heroically repelled all attacks, but they were overwhelmed by the number of attackers. When almost all the defenders of the battery had already fallen, the division commander, old General Likhachev, wounded, rushed at the French with a sword in his hands. The French captured Likhachev, who was stabbed with bayonets. The battery was captured. Many of its defenders died the death of heroes. The remnants of the 24th division and other infantry units withdrew at about 16 o'clock under the protection of the fire of a battery located at a distance at a height."

In the report presented to Kutuzov, Dokhturov wrote: “I make it my duty to convey that, having arrived at it (Bagration’s army. - VC.), found the heights and redoubts previously occupied by our troops, taken by the enemy, as well as the ditch that separated us from it. Having made it my most important goal to maintain my current position, I made the necessary orders in this case, ordering the detachment commanders to take all measures to reflect the enemy’s desire and not to give up any real places. Everyone did this with excellent prudence, and although the enemy, who had decided to overthrow our left flank, attacked with all his might under terrible artillery fire. But these attempts were completely destroyed by the measures taken and the unparalleled courage of our troops. The guards regiments - Lithuanian, Izmailovskaya and Finland - throughout the battle showed worthy Russian courage and were the first who, with their extraordinary courage, restrained the enemy’s desire, hitting him everywhere with bayonets. The other guards regiments - Preobrazhenskaya and Semenovskaya - also contributed to repelling the enemy with fearlessness. In general, all the troops that day fought with their usual desperate bravery, so that from the time I took command until nightfall, which stopped the battle, all points were almost held, except for some places that were ceded due to the need to withdraw the troops from the terrible grapeshot fire, great damage the one who caused it. But this retreat was a very short distance with due order and with the infliction of damage to the enemy in this case ... "

Late in the evening, Dokhturov arrived at Kutuzov and said: “I saw with my own eyes the retreat of the enemy and I consider the Battle of Borodino completely won.” Victory was certain, especially in strategic terms. However, the losses in the army were great, and, wanting to preserve the army, on August 27, Kutuzov gave the order to move the troops six miles back to Mozhaisk. When the army retreated, Dokhturov led a column consisting of the 2nd Army, as well as the 4th and 6th Corps of the 1st Army.

On September 1st at 5 pm a military council was held in Fili. By this time, a rather unfavorable situation had created for the Russian army. Already on August 30, the French moved in the direction of Ruza and further to Zvenigorod. News was received of a flanking bypass of Moscow by Poniatowski's corps from the south, along the Borovskaya road. The reinforcements that Kutuzov expected to receive from Moscow Governor Rostopchin did not arrive. In addition, Barclay de Tolly and Ermolov, who examined the position chosen by Bennigsen for the battle near Moscow, found it completely unsuitable.

At the council, opinions were divided. Barclay de Tolly proposed to retreat through Moscow to the Vladimir road. Osterman, Raevsky, as well as Colonel Tol spoke in favor of surrendering Moscow without a battle. Bennigsen insisted on fighting, considering the position he had chosen to be impregnable. Konovnitsy, Platov, Uvarov and Ermolov spoke out in favor of battle, but at the same time recognized Bennigsen’s position as unsuitable. It was possible to attack the French on the march, but in this case it was difficult to predict the outcome of events. Dokhturov saw that the position chosen by Bennigsen was very reminiscent of the one that was under Friedland, when, through Bennigsen’s fault, the Russian army was defeated. But as a patriot, for whom the name of Moscow was sacred, Dokhturov could not imagine that the capital could be surrendered without a fight. Dokhturov spoke out in favor of battle.

In his memoirs about the military council in Fili, Ermolov wrote: “General Dokhturov said that it would be good to go towards the enemy, but that in the Battle of Borodino we lost many honest commanders, and placing the attack on the officials who took their places, little known, one cannot be completely sure in success."

The decision made by Kutuzov was unexpected for Dokhturov, and he chewed hard on the upcoming retreat. Bennigsen, in a note he compiled for the emperor, indicates that during the discussion Dokhturov made him “a sign with his hand that his hair stood on end, hearing that the proposal to surrender Moscow would be accepted.” The feelings that possessed Dokhturov can be judged from his letter to his wife: “...I am in despair that they are leaving Moscow! Horrible! We are already on this side of the capital. I am making every effort to convince them to meet the enemy. (...) What a shame for the Russians: to leave their Fatherland, without the slightest shot of a rifle and without a fight. I’m furious, but what can I do?” This confession by Dokhturov testifies to the responsibility Kutuzov took upon himself when deciding to leave Moscow. Few could understand his actions, if even such comrades as Dokhturov considered it impossible to surrender Moscow without a battle.

Having completed the Tarutin maneuver, Kutuzov advanced Dokhturov’s corps towards Moscow. Soon the commander-in-chief received a message from Dorokhov about the attempts of the Ornaro and Brusier divisions to bypass the Russian flank in the Fominsky area. Kutuzov ordered Dokhturov, who, in addition to the 6th Corps, had at his disposal the Meller-Zakomelsky cavalry corps, six Cossack regiments, one Jaeger regiment and artillery, to move to the area of the village of Fominsky. At dawn on October 10, Dokhturov began moving towards the French.

Arriving in Aristovo, Dokhturov received data from Dorokhov, based on which he sent a message to Kutuzov: “Major General Dorokhov was with me this minute... All the forces that Major General Dorokhov saw in the indicated places, he assures, do not exceed eight or nine thousand . He also noticed that near Fominskoye and across the Nara River at this village there are bivouacs and lights and artillery are visible, but due to the very wooded areas, it is impossible to determine the enemy’s forces.” Following Dorokhov, the commander of the partisan detachment A.N. Seslavin arrived at Dokhturov’s headquarters with captured Frenchmen, whom he had already interrogated. Having received new data, Dokhturov immediately drew up a report to the commander-in-chief and sent it with the duty officer D.N. Bolgovsky.

In his report, Dokhturov said: “Captain Seslavin has now delivered the information he learned from the prisoners, uniformly showing that in the village of Bekasovo, six miles from Fominsky, the corps of the 1st Marshal Ney, two guard divisions and Napoleon himself camped for the night. This is the fifth day that these troops have left Moscow and that other troops are marching along the same road... Major General Dorokhov informs that he has received a report that the enemy has broken into Borovsk.”

At night, Bolgovsky delivered a report to Kutuzov. After listening to the officer, Kutuzov said the famous words: “...From this moment, Russia is saved.”

According to information from the prisoners, it was clear that the main forces of the French were moving in the direction of Maloyaroslavets. Dokhturov was able to appreciate the strategic importance of this district town and, without waiting for Kutuzov’s orders, moved his units on a forced march to Maloyaroslavets.

Having received the report, Kutuzov gave the order to Dokhturov to move to Maloyaroslavets as quickly as possible. Dokhturov received the order already on the march. At the same time, Kutuzov moved his main forces from Tarutin towards Maloyaroslavets, sending Platov forward to help Dokhturov.

On the evening of October 11, troops under the command of Dokhturov approached the village of Spassky, five miles from Maloyaroslavets. But the movement of his troops was suspended due to the fact that the peasants, hearing about the approach of the French, destroyed bridges across the Protva River. It was necessary to urgently build a crossing, and only after midnight the troops crossed to the other side. By dawn on October 12, Dokhturov approached Maloyaroslavets, which had been occupied by the French since the evening of October 11.

At 5 o'clock in the morning a fierce battle ensued. By the time Dokhturov approached, the city was occupied by two battalions from the Delzon division of the main corps of the French army under the command of Viceroy Eugene Beauharnais. Dokhturov brought the 33rd and 6th Jaeger regiments into battle, which drove back the French. Delzon abandoned additional units of his division and entered the city. Then Dokhturov sent the 19th Jaeger Regiment, led by Ermolov, who again drove the French out of the city. At the same time, the rest of Dokhturov’s infantry occupied the heights and blocked the road to Kaluga, and Meller-Zakomelsky’s cavalry corps and Dorokhov’s detachment blocked the road to Spasskoye. Dokhturov concentrated his artillery in front of his corps and in infantry combat formations. Delzon brought the entire division into battle, and the battle became fierce.

From the book The Conquest of America by Ermak-Cortez and the Rebellion of the Reformation through the eyes of the “ancient” Greeks author1. Herodotus returns to the story of the murdered Russian Horde prince Dmitry “Antique” False Merdis - this is Dmitry, the son of Elena Voloshanka, or Dmitry the Pretender Herodotus still cannot escape the events of the late 16th - early 17th centuries. As we already said, now it has become

From the book Calif Ivan author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich29. Dmitry Ivanovich, “False Dmitry” 29a. DMITRY IVANOVICH (FALSE DMITRY) “IMPOSTER”, “THIEF” 1605–1610, ruled for 5 years, fig. 192–195. The son of Tsar Ivan V Ivanovich, deprived of power in 1572. He was tonsured a monk, but fled to Poland and began a struggle for power. Eventually seized the throne

From the book How Brezhnev replaced Khrushchev. The secret history of the palace coup author Mlechin Leonid MikhailovichOur Nikita Sergeevich On that September day in 1971, when Khrushchev was taken to the hospital, from where he would never return, on the way Nikita Sergeevich saw corn crops. He said sadly that they had sown it wrong, the harvest could have been greater. The wife, Nina Petrovna, and the attending physician asked

From the book History of Humanity. Russia author Khoroshevsky Andrey YurievichStanislavsky Konstantin Sergeevich Real name - Konstantin Sergeevich Alekseev (born in 1863 - died in 1938) Russian actor, director, teacher, theorist and reformer of modern theater. Founder and first director of the Moscow Art Theater. People's

author Strigin Evgeniy MikhailovichGorbachev Mikhail Sergeevich Biographical information: Gorbachev Mikhail Sergeevich, born March 2, 1931, native of the village of Privolnoye, Krasnogvardeisky district, Stavropol Territory. Higher education, graduated from the Law Faculty of Moscow State University in 1955

From the book From the KGB to the FSB (instructive pages of national history). book 2 (from the Ministry of Bank of the Russian Federation to the Federal Grid Company of the Russian Federation) author Strigin Evgeniy MikhailovichLikhachev Dmitry Sergeevich Biographical information: Dmitry Sergeevich Likhachev was born in 1906. Higher education. Known as a literary critic and public figure. In 1928–1932 he was

From the book Personalities in History. Russia [Collection of articles] author Biographies and memoirs Team of authors --Dmitry Venevitinov Dmitry Zubov At the age of fourteen he translated Virgil and Horace. At sixteen he wrote the first poem that has come down to us. At seventeen he became interested in painting and composing music. At eighteen, after a year of studying, he successfully passed his final exams at

From the book Heroes of 1812 [From Bagration and Barclay to Raevsky and Miloradovich] author Shishov Alexey VasilievichDmitry Dokhturov One of the most famous commanders of the “thunderstorm of the 12th year” D.S. Dokhturov (Doctors) came from hereditary nobles of the Tula province, known in history since the 16th century. He was born in 1759 in the village of Krutoye, Kashira district, Tula province (now

authorMikhail Sergeevich Barabanov Born in 1919. After graduating from the Borisoglebsk Aero Club, he was sent to the Krasnodar Military Aviation School. During the Second World War, he fought in three regiments - the 286th, 45th and 15th IAP. He distinguished himself in the Kerch operation. Fought in Kuban, in

From the book Soviet Aces. Essays on Soviet pilots author Bodrikhin Nikolay GeorgievichKumanichkin Alexander Sergeevich Born on August 26, 1920 in the village of Balanda, now the city of Kalininsk, Saratov region. In 1930 he moved to Moscow with his family. Graduated from 7th grade, FZU school, flying club. In 1938 he was sent to the Borisoglebsk Military Aviation School, from which he graduated

From the book Soviet Aces. Essays on Soviet pilots author Bodrikhin Nikolay GeorgievichMakarov Arkady Sergeevich Born on March 6, 1917 in Samara. Graduated from 7 classes and workers' school. In 1938 he graduated from the Kachin Military Aviation School. At the front, Makarov fought in MiG-3, Yak-1, La-5, La-7 fighters. By September 1943, the flight commander of the 32nd Guards Guard Lieutenant

From the book Soviet Aces. Essays on Soviet pilots author Bodrikhin Nikolay GeorgievichRomanenko Alexander Sergeevich In July 1941, in one of the October battles near Narofominsk, Romanenko won a rare triple victory at that time, shooting down 3 Yu-88s on a donkey! For combat work in the Mozhaisk and Zvenigorod directions he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

From the book Holy Patrons of Rus'. Alexander Nevsky, Dovmont Pskovsky, Dmitry Donskoy, Vladimir Serpukhovskoy author Kopylov N. A.Prince Dmitry Ivanovich and Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich in the struggle for the grand ducal label The successes of their predecessors and the weakening of the Golden Horde opened up the prospects for a new military-political course for the young Moscow prince Dmitry Ivanovich. He is the first of

From the book The First Defense of Sevastopol 1854–1855. "Russian Troy" author Dubrovin Nikolay FedorovichVladimir Sergeevich Kudrin Junior doctor of the 31st naval crew. He was part of the Sevastopol garrison throughout the defense. At first he was at the Naval Hospital, where he was during the first bombing. Having taken up duty on the eve of the bombing, he was

(1761-1816) - General of the Infantry, Chief of the Moscow Infantry Regiment, came from poor nobles (the founder of the Dokhturovs, Kirill Ivanovich, left Constantinople for Moscow under Ivan the Terrible) and was one of the leaders of whom the Russian army is especially proud. Extraordinary courage in connection with the same modesty, straightforwardness, responsiveness and kind heart - made him a knight without fear or reproach and earned him the ardent love of all who knew him... D. was registered for service as a page at the court of His Imperial Majesty in 1771 , in 1777 he was a chamber page, and in 1781 he was promoted to lieutenant of the Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment; in 1788 D. is listed as captain of the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment. The future hero's baptism of fire took place during the Swedish War, during an operation against the Swedish rowing fleet. Already here D. fully revealed his brilliant military qualities and was wounded twice: in 1789 - in the right shoulder and in 1709 - in the leg. Empress Catherine II honored the courage of the young officer with a golden sword with the inscription “for bravery.” In 1795, Dokhturov was transferred with the rank of colonel to the army, to the Yeletsk infantry regiment. In 1797 he was promoted to major general and appointed chief of the Sofia infantry regiment, and in 1799 he was promoted to lieutenant general.

In 1801, Dokhturov was chief of Yeletsky, and in 1803, chief of the Moscow Infantry Regiment, in which he was promoted to infantry general in 1810.

In 1805, D. brilliantly distinguished himself in the battle of Dirnstein (on the left bank of the Danube, a little above Krems), where he commanded a strong column secretly directed to the rear of the French.

The actions of this column had a decisive influence on the success of the battle, and D. earned the Order of St. George 3rd Art. In the same year, in the unfortunate and famous battle of Austerlitz, D. commanded the 1st column on the left wing of the Allies.

This column, and the entire left wing, owed their salvation to his extraordinary courage and stewardship.

When it became clear that the battle was lost, the 1st Column had to retreat under extremely difficult conditions, breaking through the ranks of the enemy.

To cover the only route of retreat between the Sagan and Menitsky lakes, D. ordered the New Ingermanland regiment to occupy the village of Telnits.

The courage of this regiment and the successful actions of the Kienmayer vanguard, which occupied Auezd, helped the retreat of the remnants of our left wing, which lost many killed, wounded, prisoners and guns.

Having made his way through the enemy, D. joined the other troops, who considered him either already dead or captured. They say that when, setting an example for the troops, he drove up to a dam under fire from enemy batteries, the most dangerous point on the battlefield, the adjutants began to ask D. to leave this place, reminding him that he had a wife and children. D. answered this: “Here my wife is an honor, the troops entrusted to me are my children,” and, drawing his golden sword, cried out: “Guys, here is the sword of our mother Catherine! We will die for the Father of the Sovereign and the glory of Russia.

Hooray! God and Alexander are with us." For his feat in the Battle of Austerlitz, Dokhturov received the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd class of the Grand Cross.

During the campaign of 1806-1807, participating in many battles, D. was shell-shocked at Preussisch-Eylau and wounded at Heilsberg, but in both cases did not leave the battlefield until the end of the battle. The reward of his courage and prudent orders was a sword decorated with diamonds, the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky and the Prussian Red Eagle. In the battle of Friedland, D., being in the center of our extremely unfavorable position, courageously repelled the onslaught of the French, led by Emperor Napoleon himself, and then the difficult lot fell on him to cover the transition of our troops, which took place under the energetic onslaught of the enemy, across the river. Hello. Here his incomparable courage, composure and management showed out in full brilliance.

Being already on the other side of the river. Alla, D. noticed that in one of the regiments there was confusion, which, under the given circumstances, threatened to turn into panic.

Then D., without hesitating for a moment, threw himself into the river, swam across it on a horse, put the disordered columns in order and returned back the same way. The 1812 campaign found Infantry General Dokhturov commander of the 6th Corps in Barclay de Tolly's 1st Army. The unexpected start of the war and the march of Napoleon's main forces, which cut the center of the 1st Army, put the 6th Corps, stationed in Lida, in the most difficult situation.

To avoid a separate defeat, the 6th Corps had to make an extremely difficult and long flank march. Guarded by the side and head vanguards, D. headed through Olshany into the gap between Smorgon and Mikhalishki and managed to fight between the French and get in touch with the main forces retreating to the Drissky fortified camp.

The march on July 19 was especially difficult, when the 6th Corps had to make 42 miles to pass Mikhalishki and not be cut off by the French cavalry.