Roman slaves. Legal status of slaves in ancient Rome How slaves lived in ancient Rome story

Roman society was never homogeneous. The status of the inhabitants of the empire varied depending on their place of birth and condition. The main division between freemen and slaves did not abolish the thousands of minor gradations within these two main groups. Free people could be called citizens, or they could bear the name of pilgrims - representatives of other cities in Italy, and later - other peoples that were part of the empire. Slaves could be public or private, prisoners of war, bought at the market or born in the house. The latter were especially valued, since, on the one hand, they knew no other life, and on the other, they were perceived by the owners as family members - surnames.

Roman slavery was noticeably different from Greek: it, like everything in the Latin world, bore the imprint of legal.

Slavery in Rome

Before the law, a slave had no rights. All slaves who lived under the master's roof were subject to the death penalty if the owner was killed in the house. However, during the imperial era, punishments were also introduced for owners for cruelty to their slaves. A slave could occupy a privileged position, such as a butler or a favorite concubine. The merits of a slave to his master were often grounds for emancipation. Emancipation by master's will for private slaves or by act of a magistrate for public slaves was widespread. In some cases, a slave who became rich acquired his own slaves. And freedmen, engaged in trade, sometimes acquired an exceptionally high position in Roman society. All this did not cancel the difficult situation of the masses of slaves who worked in the Roman household, but it showed the ways by which a clever, quick-witted or simply devoted slave could gain freedom.

Social life and citizenship in Rome

The social life of Rome was much more complex and intense compared to Greek. The Romans, even in the republican period, gravitated towards the all-embracing state power. During the Republic, Rome was governed by a whole army of elected officials: consuls, praetors, quaestors, censors, tribunes, aediles, prefects... Their functions were clearly defined and did not overlap. Unlike neighboring peoples, and primarily the Hellenes, they willingly shared their citizenship not only with pilgrims, but also with freedmen. At the same time, obtaining citizenship was tantamount to obtaining nationality. Blood didn't matter. The main thing was a common way of life for all citizens and obedience to common laws. Convinced of their own exclusivity, even messianism, the Romans were nevertheless not nationalists in the sense in which, for example, one can call the Athenians nationalists, who even looked at them as second-class citizens. For the Roman, the line between a civilized person and a barbarian lay in the way of life and was defined quite simply. A cultured person lives in a city, wears a toga, owns slaves, and obeys the laws. The barbarian lives in the forest, wears pants made of animal skins, he will be very lucky if he falls into slavery and can serve to strengthen Rome. if he works well and internalizes Roman ideals, the owner will set him free, and lo and behold, he will help him obtain citizenship. So, gaining civil rights- this is literally a remelting in the crucible of another culture.

However, it would be wrong to see in Roman citizenship some kind of analogue of modern citizenship. Citizenship - belonging to the city - for a long time could not become a national institution in Rome. The inhabitants of other Italian cities had their own citizenship, although they lived in the same country as the Romans. An intermediate stage on this path was the provision of dual citizenship, for example, Rome and Capua, Rome and Mediolanum, etc. But this did not solve all the problems. The Romans understood that the stability of their state was directly related to the expansion of the number of citizens. By the beginning of the new era, of the 50 million subjects of Rome, only about a million had the status of citizen. Emperor Caracalla in 212, in the so-called Antonine Constitution, gave Roman citizenship to all free people, regardless of nationality, living in the territory of the empire. Roman citizen usually had three names: personal (Gai), family (Julius) and family or nickname (Caesar). A freed slave received the personal and family name of his master. Thus, the slave and close friend of Cicero - Tyrone, freed in 53 BC. e., became known as his master, Marcus Tullius, and acquired Roman citizenship.

Roman society was characterized by high social mobility. Belonging to one or another class was determined depending on the property qualification. City authorities, in accordance with the assessment of their condition, assigned residents to classes that were not inherited. Thus, a rich artisan could slip into the equestrian class, don a gold ring and a white toga with a thin purple stripe.

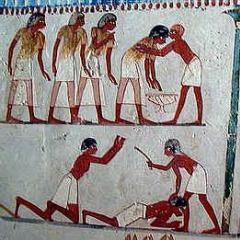

Throughout the history of mankind, many cases have been recorded when laws were applied to certain categories of people that equated them to objects of property. For example, it is known that such powerful states as Ancient Egypt were built precisely on the principles of slavery.

Who is a slave

For thousands of years, the best minds of humanity, regardless of their nationality and religion, fought for the freedom of every individual and argued that all people should be equal in their rights before the law. Unfortunately, it took thousands of years before these requirements were reflected in the legal norms of most countries of the world, and before that, many generations of people experienced for themselves what it means to be equated with inanimate objects and deprived of the opportunity to manage their lives. To the question: “Who is a slave?” You can answer by quoting the UN. In particular, it states that such a definition is suitable for any person who does not have the ability to voluntarily refuse to work. In addition, the word “slave” is also used to refer to an individual who is owned by another person.

How did slavery arise as a mass phenomenon?

No matter how strange it may sound, historians believe that the development of technology served as a prerequisite for the enslavement of people. The fact is that before an individual was able to create with his labor an amount of product greater than what he himself needed to maintain life, slavery was not economically feasible, so those who were captured were simply killed. The situation changed when, thanks to the advent of new tools, farming became more profitable. The first mention of the existence of states where slave labor was used dates back to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. e. Researchers note that we are talking about small kingdoms in Mesopotamia. Numerous references to slaves are found in the Old Testament. In particular, it indicates several reasons why people moved to the lower rung of the social ladder. Thus, according to this Book of Books, slaves are not only prisoners of war, but also those who were unable to pay a debt, married a slave, or thieves who were unable to return what was stolen or compensate for the damage caused. Moreover, the acquisition of such a status by a person meant that his descendants also had practically no legal chance of becoming free.

Egyptian slaves

To date, historians have not yet come to a consensus regarding the status of “unfree” people in the Ancient Kingdom ruled by the pharaohs. In any case, it is known that slaves in Egypt were considered part of society and were treated quite humanely. There were especially many people of forced labor there during the era of the New Kingdom, when even ordinary free Egyptians could have servants who belonged to them by right of ownership. However, as a rule, they were not used as agricultural producers and were allowed to start families. As for the Hellenistic period, slaves in Egypt under the rule of the Ptolemies lived in the same way as their fellow sufferers in other states that formed after the collapse of the empire of Alexander the Great. Thus, it can be stated that until about the 4th century, the economy of the most powerful of the countries located in the north of the African continent was based on the production of agricultural products by free peasants.

Slaves in Ancient Greece

Modern European civilization, and even earlier the ancient Roman one, arose on the basis of the ancient Greek one. And she, in turn, owed all her achievements, including cultural ones, to the slave-owning mode of production. As already mentioned, the status of a free person in the ancient world was most often lost as a result of captivity. And since the Greek city-states constantly waged wars among themselves, the number of slaves grew. In addition, this status was assigned to insolvent debtors and meteks - foreigners who were hiding from paying taxes to the state treasury. Among the occupations that most often included the duties of slaves in Ancient Greece are housekeeping, as well as work in mines, in the navy (rowers) and even service in the army. By the way, in the latter case, soldiers who showed exceptional courage were released, and their owners were compensated for the loss associated with the loss of a slave at the expense of the state. Thus, even those who were born unfree had a chance to change their status.

Roman slaves

As historical documents that have survived to this day testify, in Ancient Greece, the majority of people deprived of the right to manage their lives were Greeks. Things were completely different in Ancient Rome. After all, this empire was constantly at war with its many neighbors, which is why Roman slaves were predominantly foreigners. Most of them were born free and often tried to escape and return to their homeland. In addition, according to the Laws of the Twelve Tables, which are completely barbaric in the understanding of modern man, a father could sell his children into slavery. Fortunately, the latter provision lasted only until the adoption of the Petelian Law, according to which slaves in Roman law are anyone, but not Romans. In other words, a free man, a plebeian, and even more so a patrician could in no case become a slave. At the same time, not all people in this category had a bad life. For example, domestic slaves were in a rather privileged position and were often perceived by their owners as family members. In addition, they could be released according to the will of the master or for services to his family.

The most famous Roman slave revolts

The desire for freedom lives in every person. Therefore, although the owners believed that their slaves were something between inanimate tools of labor, they often rebelled. These cases of mass disobedience were usually brutally suppressed by the authorities. The most famous event of this kind - recorded in historical documents - is considered to be the slave uprising led by Spartacus. It took place between 74 and 71 AD, and was organized by gladiators. Historians attribute the fact that the rebels managed to keep the Roman Senate at bay for about three years to the fact that at that time the authorities did not have the opportunity to send trained military formations against the slave army, since almost all the legions fought in Spain, Asia Minor and Thrace. Having won several high-profile victories, the army of Spartacus, the backbone of which was made up of Roman slaves trained in the martial arts of that time, was nevertheless defeated, and he himself died in the battle, presumably at the hands of a soldier named Felix.

Revolts in Ancient Egypt

Similar events, but, of course, much less well-known, took place many centuries before the founding of Rome, on the banks of the Nile, at the end of the era. They are described, for example, in the “Teachings to Noferrehu” - a papyrus that is kept in the St. Petersburg Hermitage. True, this document notes that the uprising was raised by poor peasants, and only then slaves, mostly from and the privileges of the rich. This means that the slaves believed that the unjust laws of Egypt, which divided people into free and slave, were to blame for their plight. Like the Spartacus uprising, the Egyptian rebellion was also suppressed, and most of its participants were mercilessly destroyed.

Ancient Roman laws regarding slaves

As you know, modern laws in many countries are based on Roman law. So, according to it, all people were divided into two categories: free citizens (the privileged part of society) and slaves (this is the lowest, so to speak, caste). According to the law, an unfree person was not considered an independent subject of law and did not have legal capacity. In particular, in most situations - from a legal point of view - he acted either as an object of legal relations, or as a “speaking instrument”. Moreover, if a slave married a free woman or a slave married a free man, they could not claim freedom. In addition, for example, all slaves who lived with their master under the same roof had to be executed if their master was killed within the walls of the house. To be fair, it must be said that during the era of the Roman Empire, i.e. after 27 BC, punishments were introduced for masters for cruel treatment of their own slaves.

Laws Regarding Slaves in Ancient Egypt

The attitude towards slaves in the state ruled by the pharaohs was also formalized legally. In particular, there were laws that prohibited the killing of slaves, guaranteed them food, and even required payment for some types of slave labor. It is interesting that in some legal acts slaves were called “dead family members,” which researchers associate with the characteristics of the inhabitants of Ancient Egypt. At the same time, the children of a free man born by a slave could, at the request of their father, receive the status of free and even claim a share of the inheritance on an equal basis with legitimate offspring.

Slavery with the USA: the legal side of this issue

Another state whose economic prosperity at an early stage of development was based on the use of slave labor is the United States. It is known that the first black slaves appeared on the territory of this country in 1619. Negro slaves were imported into the United States until the mid-19th century, and scholars estimate that a total of 645,000 people were transported to this country by slave traders from Africa. Interestingly, most of the laws affecting such “reluctant emigrants” were passed in the last decades before the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment. For example, in 1850, the US Congress passed an act worsening the legal status of slaves. According to it, the population of all states, including those where slavery had already been abolished at the time of its adoption, was ordered to take an active part in the capture of fugitive slaves. Moreover, this law even provided for punishment for those free citizens who helped blacks who ran away from their masters. As you know, despite all the attempts of planters from the Southern States to preserve slavery, it was still prohibited. Although for about a century, various US states had segregation laws that were humiliating for the black population and infringed on their rights.

Slavery in the modern world

Unfortunately, the desire to enjoy the fruits of other people’s labor for free has not been eradicated to this day. Therefore, information is received daily about the identification of more and more cases of trafficking - buying, selling and exploiting people. Moreover, modern slave traders and slave owners sometimes turn out to be much more cruel than, for example, Roman ones. After all, thousands of years ago the legal status of slaves was specified, and they were only partially dependent on the will of their masters. As for the victims of trafficking, very often no one knows about them, and unfortunate people are toys in the hands of their “masters.”

4. Slavery

When Schopenhauer (Parerga, xi, 217) says that there is a wealth of evidence, old and new, to support “the belief that man is superior to the tiger and the hyena in cruelty and ruthlessness,” he could find much of the same evidence in the accounts of the Roman treatment of slaves . The renowned scholar Birt went to great lengths to prove that, on the whole, life for a slave in Rome was not too terrible. But we must conclude that the picture he painted, although correct, still suffers from one-sidedness. We should not make the same mistake, but with the opposite sign, so we are obliged to admit the justice of everything that has been said about the better sides of Roman slavery, which at times may have been quite easy. But now we will show the other side of the life of a slave in Rome.

Of course, it is obvious that no one would torture such valuable property as a slave continuously - and least of all in ancient times, when each person had several slaves, next to whom his whole life passed. It has been established that the first slaves in Rome were prisoners of war. Perhaps, as Mommsen believes, this is where the bonds of sacred duties that bind master and slave originate. Thus, a slave was never allowed to testify against his master. On the other hand, the state always protected the owner from the slaves, sent officials to search for runaway slaves and sentenced all slaves in the house to death if one of them killed the owner. This is dealt with in a famous passage from Tacitus (Annals, xiv, 42), and we must consider it in detail, since it illuminates the true attitude of the law towards slaves, no matter how gently their masters treat them. Here is this passage: “The prefect of the city of Rome, Pedanius Secundus, was killed by his own slave, either because, having agreed to release him for a ransom, Secundus refused him this, or because the murderer, overcome by passion for the boy, did not tolerate a rival in the person of his master. And when, in accordance with the ancient institution, all the slaves who lived under the same roof with him were gathered to be led to execution, the common people came running, standing up for so many innocent people, and it came to street riots and gatherings in front of the Senate, in which there were also resolute opponents of such exorbitant severity, although the majority of senators believed that the existing order could not be changed.”

The famous lawyer Gaius Cassius gave an impassioned speech in defense of the cruel law. Tacitus continues: “No one dared to speak out against Cassius, and in response to him only indistinct voices were heard regretting the fate of so many doomed, most of whom undoubtedly suffered innocently, and among them were old people, children, women; Nevertheless, those who insisted on execution prevailed. But this sentence could not be carried out, since the gathered crowd threatened to take up stones and torches. Then Caesar, having scolded the people in a special decree, set up military barriers along the entire route along which the condemned were to follow to execution.”

The brilliant scholar Star, in his remarkable translation of Tacitus, rightly points out that the behavior of the crowd demanding an end to the brutal execution of 400 innocent people stands in stark contrast to the cowardice and cruelty of the rich and noble senators. It was the fear of millions of slaves suffering under the yoke of the rich that forced them to insist on such a terrifying sentence.

The inexorable law made the situation of slaves in Rome intolerable. A slave was not a person, but a thing that its owner could handle at his discretion. In Gaius's Institutions (i, 8, i) it is said: “Slaves are at the mercy of their masters; among all nations, masters have power over the life and death of slaves.”

We should not be surprised, therefore, that few masters felt obliged to care for old and sick slaves. Cato the Elder advises selling “old oxen, spoiled cattle, spoiled sheep, wool, skins, an old cart, scrap iron, a decrepit slave, a sick slave, and generally sell everything that is unnecessary.” Cicero once said that in a moment of danger it is better to lighten the ship by throwing an old slave overboard than a good horse. It is true that the most heinous cruelties towards slaves took place in the later era, when huge numbers of slaves were in the possession of individuals; hence the saying “One hundred slaves - one hundred enemies.” But Plautus, who lived about two centuries before Christ, shows that flogging and constant fear of crucifixion were always present in the life of a slave.

Appian writes about the treatment of slaves in a besieged city (Civil Wars, v, 35). We are talking about Perusia around 38 BC. BC: “Having calculated how much food was left, Lucius forbade giving it to the slaves and ordered to ensure that they did not run away from the city and did not let the enemies know about the difficult situation of the besieged. Slaves wandered in crowds in the city itself and near the city wall, falling to the ground from hunger and eating grass or green leaves; Lucius ordered the dead to be buried in oblong pits, fearing that the burning of the corpses would be noticed by enemies, and if they were left to decompose, stench and disease would begin.”

If slaves in general were treated as human beings, then there would not be those slave rebellions that escalated into real wars. Diodorus, who understood this, writes: “When excessive power degenerates into atrocities and violence, the spirit of conquered peoples comes to extreme despair. Anyone who has been given the lot of a subordinate position in life calmly cedes the right to glory and greatness to his master; but if he does not treat him like a human being, he becomes the enemy of his cruel master.”

These uprisings were replete with examples of incredible cruelty. Let us note a few particularly interesting points. We read from Diodorus describing the revolt in Sicily around 240 BC. e. (xxxiv, 2): “For about sixty years after Carthage lost power over the island, the Sicilians flourished. Then a slave revolt broke out, and this is what caused it: since the Sicilians acquired enormous property and accumulated colossal wealth, they bought many slaves. Slaves were brought in from prison in droves and immediately branded with special marks. The young were assigned to livestock herding, the rest received suitable occupations. Their work was very hard, and they were given almost no clothing or food. The majority found their livelihood through robbery; Murders took place everywhere, gangs of robbers roamed the country. The governors tried to put an end to this, but could not punish these slave-robbers, since their masters were too powerful. They could only watch powerlessly as the country was plundered. The owners were mostly Roman horsemen, and the governors were afraid of them, since they were invested with the power to judge all officials convicted of crimes. The slaves could no longer tolerate their desperate situation and frequent, causeless punishments; At every opportunity, they gathered and talked about rebellion and, finally, having mustered up their resolve, they took action.”

The history of this uprising amazes us with its boundless horror. Diodorus (ibid.) describes the actions of the rebel slaves this way: “They broke into houses and killed everyone. At the same time, they did not spare even infants, but tore them out of the hands of their mothers and smashed them to the ground. Not a single language would dare describe all the monstrous atrocities that were committed against women in front of their husbands.”

Diodorus mentions the Roman landowner Damophilus and his wife Megallis, who were famous for their exceptional cruelty. (A curious and important fact: all the evidence we have is unanimous in speaking about the cruel treatment of slaves by women.) Diodorus writes that “Damophilus treated his slaves with extreme cruelty; his wife Megallis did not lag behind him in punishing the slaves, subjecting them to all sorts of atrocities.” And further: “Since Damophilus was an uneducated and ignorant man, the irresponsible possession of enormous wealth led him from arrogance to cruelty, and as a result he brought destruction on himself and on the country, buying many slaves and treating them brutally: he branded those who were born free, but were captured and enslaved. He chained some and kept them in prison, others he sent to graze cattle, without giving them either normal food or necessary clothing. Not a day passed without him punishing one of the slaves without due reason, so ferocious and merciless was he by nature. His wife Megallis took no less pleasure in inflicting horrific punishments on her maids and slaves who were under her supervision.”

All the hatred of the rebel slaves was first poured out on Damophilus and Megallis. The latter was given to the slaves, and after torture they threw her alive from a cliff; Damophilus was hacked to death with swords and axes. With amazing speed, more and more people went over to the side of the rebels - Diodorus writes about 200 thousand rebels. They won several battles with the Roman regular army, but, being besieged in several cities (where they suffered such terrible hunger pangs that they began to devour each other), they finally surrendered. Prisoners were tortured in the old fashion and then thrown off the cliffs.

Everyone knows about the Spartacus uprising. It was marked by similar horrors. In the end, the last surviving rebels - about 6 thousand people - were captured and died a painful death on crosses placed along the Appian Way.

We have already noted that Roman women became famous for their cruelty to slaves. Let us cite several important passages as proof. Ovid speaks about it this way (Science of Love, iii, 235 ff.):

Hair is another matter. Comb them freely

And spread them over your shoulders in front of everyone.

Just be calm, restrain yourself, if you get angry,

Don't make them endlessly unravel and weave!

Let your servant not be afraid of reprisals from you:

Don’t tear her cheeks with your nails, don’t prick her hands with a needle, -

It’s unpleasant for us to watch a slave, in tears and in pricks,

Curls should curl over the hated face.

He, speaking about the hair of his beloved, writes this in “Love Elegies” (i, 14):

They were obedient, - add, - capable of hundreds of twists,

They never caused you pain.

They did not break off from the pins and comb teeth,

The girl could clean them up without fear...

Often the maid dressed her up in front of me, and never

Snatching the hairpin, she did not prick the slave’s hands.

Juvenal paints an even more repulsive picture (vi, 474 ff.):

It's worth the trouble to study carefully what wives do,

What do they do all day long? If at night her back

The husband turns around, the housekeeper is in trouble, take it off, cloakroom attendant,

Tunic, the porter arrived late, supposedly, that means

Must suffer for someone else's guilt - for a sleepy husband:

The rods are broken on this one, this one is striped to blood

Lash, whip (some people hire executioners for a year).

They beat the slave, and she smears her face and her friend's

Listens or looks at the gold embroidered dress;

They flog - she reads the cross lines on the abacus;

They spank until the mistress screams to the exhausted whippers

A menacing “get out!”, seeing that this massacre was completed.

The wife's household management is no softer than the court of Phalaris.

Since she has a date, she should dress up

Better than ordinary days - and hurries to those waiting in the park

Or, perhaps, rather, at the sanctuary of the bawd - Isis.

The unfortunate Pseka tidies her hair - she herself

She was all disheveled from the dragging, and her shoulders and chest were exposed.

“Why is this curl higher?” And then the belt punishes

This hair is to blame for the criminally incorrect curling.

If a slave dropped a mirror on her mistress’s feet, she would immediately face severe punishment. Galen, in his treatise On the Passions and Their Cure, talks about a master who, in a fit of anger, would bite slaves, punch and kick them, gouge out their eyes, or mutilate them with style. There is evidence that the mother of Emperor Hadrian beat her slaves in anger. Chrysosom mentions a mistress who undressed her maid, tied her to a bed and flogged her so hard that people passing along the street could hear the wretched girl’s screams. The punished girl showed everyone her bloody back when she accompanied her mistress to the bathhouse.

The fact that especially cruel owners fed lamprey slaves in their cages is not fiction, but reality. Seneca writes on this subject (“On Mercy,” i, 18; “On Wrath,” iii, 40): “Although everything is permitted in relation to slaves, the law common to all living beings prohibits acting in a certain way against anyone. Any person should hate Vedius Pollio even more than his slaves hated him, for he fed moray eels with human blood and ordered anyone guilty to be thrown into a reservoir, which was nothing more than a pit with snakes. He deserved thousands of deaths, regardless of whether he fattened moray eels for his table by throwing slaves at them, or kept moray eels only to feed them in this way.”

The second passage is more clear: “August... dined with Vedius Pollio. One of the slaves broke the crystal bowl; Vedius ordered to seize him, intending him for a by no means ordinary execution: he ordered him to be thrown to the moray eels, which he kept in his huge pool. Who can doubt that this was done to satisfy the whim of a man pampered by luxury? It was brutal cruelty. The boy escaped from the hands of those holding him and, throwing himself at Caesar’s feet, begged for only one thing: that he be allowed to die any other death, just not to be eaten. Alarmed by hitherto unheard-of cruelty, Caesar ordered the boy to be released and all the crystal bowls to be broken in front of his eyes, filling the pool with fragments. So he used his power for good.”

But the gentle treatment of slaves, to which the humane Seneca calls, has always been an exception, as we see from his own words: “In relation to slaves, everything is permitted.” Unfortunately, the words of Galen (“On the Judgments of Hippocrates and Plato,” vi, extr.), apparently, do not sin at all against the truth: “Such are those who punish their slaves for offenses with burns, cut off and mutilate the legs of fugitives, deprive thieves hands, gluttons - stomachs, gossipers - tongues..." (see Cicero's speech in defense of Cluentius, the episode with the severed tongue (66, 187), "... in short, punishing that part of the criminal's body that served as the weapon of the crime." And Seneca himself advises Lucilius the following (“Letters to Lucilius,” 47): “Love does not coexist with fear. Therefore, in my opinion, you are doing the right thing when, not wanting your slaves to fear you, you punish them with words by beating them.” Columella and Varro speak in the same vein, but the reports of ill-treatment of slaves are much more numerous, and, of course, the suspicion and severity of the masters increased with the increase in the number of slaves, and therefore ever more sophisticated tortures were invented.

As for the number of slaves in Rome, the following figures can be given: Aemilius Paulus, according to some sources, brought 150 thousand captives to Rome, and Marius brought 60 thousand Cimbri and 90 thousand Teutones. Josephus claims that at the end of the 1st century AD. e. There were up to a million slaves in Rome. The Mediterranean became the scene of a vibrant slave trade, and pirates practiced kidnapping coastal inhabitants and selling them into slavery.

Finally, we must not forget that Roman law prohibited the torture of a free person, but always encouraged this cruel method of extracting testimony from slaves. The slave's testimony, given not under torture, was not taken into account at all. Torture necessarily accompanied the interrogation of any person who was not freeborn. It included all types of flogging, as well as monstrous tortures, borrowed by the Middle Ages from Rome and used for centuries in every important investigation. The instruments of torture included fidiculae– ropes for tearing joints, equuleus- goats on which they sat a slave and twisted his limbs from their joints either with a collar or with weights tied to his legs; Hot metal plates were placed on the bare skin of the slaves, and terrible leather whips, equipped with spikes and knuckles, were also used to enhance the effect. To extract a confession, investigators did not hesitate to torture even slaves. Tacitus (Annals, xv, 57) describes the torture of a slave girl from whom they sought testimony about a conspiracy against Nero: “Meanwhile, Nero, remembering that, following the denunciation of Volusius, Proculus was imprisoned by Epicharides, and believing that the female body would not endure pain, orders her to be tormented with painful torture. But neither the whips, nor the fire, nor the bitterness of the executioners, irritated by the fact that they could not cope with the woman, broke her and did not wrest her confession. So, on the first day of interrogation they did not get anything from her. When the next day they dragged her to the dungeon in a stretcher chair to resume the same tortures (mutilated on the rack, she could not stand on her feet), Epicharis, pulling the bandage from her chest and attaching a noose made from it to the back of the chair, stuck her neck through it and, leaning down with all the weight of her body, stopped her already weak breathing.”

Valery Maxim talks about a slave, “almost a child,” who was subjected to terrible torture - he was flogged, burned with metal plates, and his limbs were torn out of their joints. The author cites this case as an example of the loyalty of slaves. From his story, as well as from that of Tacitus, we see how little attention was paid to the sex and age of the tortured, unless they were freeborn. It is very interesting to trace how the Roman state, from the time of the empire, tried to take action against the most flagrant cases of cruelty towards slaves. No doubt this was partly due to changing social conditions; but perhaps the spread of humane ideas, such as we find primarily in Seneca and later in Christian writings, also played a role. Soon after the founding of the empire, a law was passed prohibiting masters from condemning their slaves to fight wild animals and transferring this right to official judges (Digests, xlviii, 8, II, 2). Since the time of Antoninus Pius, a slave who believed that he was being treated too harshly could complain to the municipal judge, and under certain circumstances could be sold to another owner. Claudius decreed that slaves abandoned by their masters due to illness became free. Adrian deprived the owners of the right to kill slaves at their own discretion and sell them to circuses, and Constantine equated the deliberate murder of a slave with the murder of a free person (“Digests”, i, 12, I; Spartan. Adrian, 18; Code of Justinian, ix, 14). A significant formula dates back to the era of Hadrian: patria potestas in pietate debet, non atrocitate consistere(“paternal authority should be expressed in love, not in cruelty”).

We must not forget that the spread of these humane views is due in no small measure to changing economic conditions. Once the Romans lost the ability to carry out further conquests and limited themselves to improving the organization and management of their colossal empire, the most important sources of slaves (importation of prisoners of war and kidnappings) decreased significantly. It is known that the number of slaves peaked at the beginning of the imperial era.

This text is an introductory fragment. From the book History of Slavery in the Ancient World. Greece. Rome by Vallon HenriVOLUME II – SLAVERY IN ROME Chapter One. FREE LABOR AND SLAVERY IN THE FIRST CENTURIES OF ROME The conclusions we have reached from studying the history of social relations in Greece regarding the influence of slavery can be verified and will find confirmation in the history of Rome. Number

From the book Sexual Life in Ancient Rome by Kiefer Otto4. Slavery When Schopenhauer (Parerga, xi, 217) says that there is a wealth of evidence, old and new, in support of “the belief that man is superior to the tiger and the hyena in cruelty and ruthlessness,” he could find a lot of similar evidence in the accounts of conversion Romans with

From the book From Slavery to Slavery [From Ancient Rome to Modern Capitalism] author Katasonov Valentin YurievichChapter VIII. Social Slavery and Spiritual Slavery Just as those who have shackles on their feet cannot walk comfortably, so those who collect money cannot ascend to heaven. St. John Climacus The slavery of wealth is worse than any torment, as all those who have been rewarded know well.

From the book History of Russia from ancient times to the beginning of the 20th century author Froyanov Igor YakovlevichSlavery Along with dependent peasants, slave slaves belonged to privately owned farms. Slaves who received a small plot of land from their master were called stradniks (strada - agricultural work). Their main responsibility was

From the book Vote for Caesar by Jones PeterSlavery Slavery was quite common in the ancient world. Most slaves were acquired in slave markets - men, women and children captured during wars or captured by pirates and then resold. They were just like you and me, with different interests.

From the book The Greatness of Babylon. History of the ancient civilization of Mesopotamia by Suggs HenrySlavery There were slaves (in the usual sense), but they never constituted the majority of the population, and the work of the entire community never depended on them. In the Early Dynastic period they were not an important social element and consisted mainly of prisoners of war. Such slaves

From the book Colonial Era author Pharmacist HerbertIII. Slavery and capitalism The first region outside Europe that evoked the righteous sighs of pious missionaries, attracted the favorable gaze of greedy merchants and the consecrated swords of gracious sovereigns, was the land mass that was located

From the book Suicide of Ukraine [Chronicle and analysis of the disaster] author Vajra Andrey7. Slavery Currently, Ukraine is the leader in Eastern Europe in terms of the number of people in slavery. Every year, 117 thousand people become victims of the slave trade in the country! Our “Svidomo” rulers are very fond of talking about the fact that a certain Ukrainian people

From the book World History. Volume 2. Bronze Age author Badak Alexander NikolaevichSlavery During the Shang (Yin) period, slaves did not have their own name, but there were several hieroglyphs to designate slaves, which was especially characteristic of the early period of slave society. For example, the hieroglyph “well,” denoting the concept of “slave,” depicted a person

From the book Pandora's Box by Gunin Lev From the book of Varvara. Ancient Germans. Life, Religion, Culture by Todd MalcolmSLAVERY Slavery existed in ancient Germany, but it is difficult for us to determine how widespread it was. Some areas had more slaves than others: for example, the Marcomanni in the 2nd century. and among the Alamanni in IV. These areas were close to the Roman borders:

author Badak Alexander NikolaevichSlavery During the Western Zhou period, slaves constituted a fairly large segment of society. Originally, the hieroglyph “min” meant “slave.” Later, the following words were used to designate: “limin”, “tsin-li”, “miaomin”, “wanming”. In a slave society, slaves

From the book World History. Volume 3 Age of Iron author Badak Alexander NikolaevichSlavery Slavery of the Homeric period differs significantly from slavery of later times. At its core, it was patriarchal in nature, as evidenced by the terms denoting their “household members,” since in Homeric times slaves were actually part of the family

From the book Man in Africa author Turnbull Colin M.Chapter 7. Slavery Obi n'kyere obi ase (No man has the right to reveal the origin of another) Akan proverb Sometimes, in defense of the European slave traders who operated in West Africa, it is said that the Africans themselves were also slave owners. Even if this is so, it

From the book Mission of Russia. National doctrine author Valtsev Sergey VitalievichSlavery Recently, in the center of Moscow, opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a monument to Emperor Alexander II was erected, on which the following words are inscribed: “He abolished serfdom in Russia in 1861 and freed millions of peasants from centuries-old slavery.”

From the book Life and Manners of Tsarist Russia author Anishkin V. G.In Ancient Rome, between the 3rd century. BC e. and II century. n. e. The slave system reached its greatest development. Therefore, the emergence, flourishing and decline of slave society can best be traced by studying the history of Ancient Rome.

Slaves appeared in Rome from time immemorial, when it was a small city, the center of a primitive agricultural people. The Romans then lived in large families - surnames. The family was headed by the “father of the family.” He controlled all the family's property, as well as the labor, fate and very lives of his children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and the few slaves who belonged to the family. Slaves were not yet very different in status from free members of the family, subordinate to its head. Both of them could not have their own property, they were represented before the law by the “father of the family”, they all participated in the cult of the patrons of the family - the Larov gods. At the altar that existed in every house, Larov the slave sought salvation from the wrath of his master.

The difference between free and unfree members of a family appeared only after the death of its head: the free themselves became the full-fledged “fathers” of their families, and slaves, along with other property, passed to the heirs of the deceased head of the family. At that time, slaves were still recognized to some extent as people. They themselves were responsible for crimes committed against strangers, even if done on the orders of the owner. In a subsistence economy, when each family provided for its own economic needs and rarely bought anything from the outside, there was no need to over-exploit the slaves who worked together with the master and his family. However, gradually the situation changed. Continuous victorious wars for land and spoils turned Rome into the center of a huge power.

The influx of material wealth, exposure to the high culture and more refined lifestyle of ancient Greece and the eastern states over time changed the old peasant Rome. Wars and participation in the exploitation of conquered provinces enriched many Romans. They bought land, built new city houses and rural villas for themselves, acquired works of art and luxury goods, and gave their children a good education.

All this required money. They could make money by selling agricultural and handicraft products. The strength of family members for its growing production was no longer enough, and besides, rich people began to despise physical labor. The free poor people preferred to enlist in the army, work on large construction projects undertaken by the state, or live on state benefits, which were paid to poor citizens from military booty and tribute from the provinces. Therefore, slaves became the main labor force in agriculture and crafts, and their number was increasing. It was in these industries that the bulk of Roman slaves were used.

But slaves were needed not only for the production of goods. The Romans' passion for spectacle, especially gladiator fights, grew, and gladiator schools were replenished with slaves. Rich Romans acquired numerous servants, among whom were not only cooks, pastry chefs, barbers, maids, grooms, gardeners, etc., but also artisans, librarians, doctors, teachers, actors, musicians. Politicians needed sufficiently dexterous and educated trusted agents who were entirely dependent on them. Slaves penetrated into all spheres of life, their numbers grew, and their professions multiplied.

The children of slaves became slaves. Provincials who owed money to Roman businessmen fell into slavery. Slaves were bought in the provinces and brought from abroad. They were supplied to special markets by pirates who captured people on ships and in coastal villages. In slave markets, natives of Greece and Asia Minor, trained in crafts and sometimes sciences, were most valued. They paid for them several tens of thousands of sesterces.

But the main number of slaves in the III-I centuries. BC e. Rome received as a result of wars of conquest and punitive expeditions. Captives captured in battle and residents of rebellious provinces were enslaved. Thus, during the reprisal against the rebel Epirus, 150 thousand people were simultaneously sold into slavery. Italics, Gauls, Thracians and Macedonians worked in agriculture. On average, a simple slave cost 500 sesterces, about the same as the cost of 1/8 hectares of land.

In the 3rd century. BC e. a law was passed equating a slave to a domestic animal. The slave was called a “talking instrument.” From now on, his master was responsible for any actions of the slave. The slave was obliged to obey him blindly, even if the master ordered him to commit murder or robbery. The owner could kill him, put him in chains, imprison him in a home prison (ergastul), turn him into a gladiator, or send him to work in the mines. And, of course, only the owner himself determined how many hours a day a slave should work and how he should be maintained. The situation of rural slaves was especially difficult. Famous figure of the 2nd century. BC e. Cato the Censor, who created a guide to farming, reduced the diet of slaves to the necessary minimum. He believed that a slave should work enough during the day to fall asleep dead in the evening: then unwanted thoughts would not come into his head. The slave was forbidden to go beyond the boundaries of the estate, communicate with strangers, or even participate in religious ceremonies. According to the law, a slave could not have a family; his family ties were not recognized. Only as a special favor could the master allow the slave to start some kind of family and raise his children.

The position of slaves in urban crafts was somewhat different. Skilled craftsmen, whose products met the tastes of the discerning buyer, could not be forced to work only under pressure. They were often given some independence and were given the opportunity to raise money for ransom. Urban slaves interacted with free artisans and the working poor on a daily basis, sometimes joining their professional and religious associations - collegiums.

Educated slaves occupied a special place. They were well maintained, often released, and in the last two centuries of the republic, many figures of Roman culture emerged from their number. Thus, the freed slaves were the first Roman playwright and organizer of the Roman theater of Libya, Andronicus, and the famous comedian Terence. The majority of doctors and teachers of grammar (including literary criticism) and oratory were freedmen.

The position of this or that group of slaves also determined its place in the class struggle. Urban slaves usually performed together with the free poor. Rural slaves had no allies, but, as the most oppressed, they were the most active participants in the uprisings of the 2nd-1st centuries. BC e. In these centuries of rapid development of slavery and especially cruel exploitation of slaves, the class struggle was very acute. Slaves fled beyond the borders of the Roman state, killed their masters, during wars they went over to the side of the opponents of Rome, which they hated, and in the 2nd century. BC e. there were rebellions more than once.

In 138 BC. e. in Sicily, where at that time there were many captive slaves from Syria and Asia Minor, the first great slave war began. The rebels chose Eunus as their king, who took the name Antiochus, usual for Syrian kings. Their second leader was a native of Cilicia, Cleon. The leaders had an elected council. The rebels managed to capture a significant part of Sicily and within six years, until 132 BC. e., successfully repel the onslaught of the Roman legions. Only with great difficulty did the Romans capture the rebel fortresses of Enna and Tauromenium, suppress the uprising and deal with its leaders.

Remains of an ancient Roman mill.

But already in 104 BC. e. A new slave revolt broke out in Sicily. A council and two leaders were again elected - Tryphon and Athenion, who was proclaimed king. They captured a vast territory. Only in 101 BC. e. The rebels were defeated and their capital, Triokalo, was captured. The Sicilian uprisings also caused an echo among the slaves of Italy, who rebelled in several cities.

Agricultural work. Roman mosaic. North Africa. III century n. e.

The struggle of the slaves reached its highest tension in the uprising of Spartacus. In 74 BC. e. 78 gladiators, among whom was the Thracian Spartacus, fled from the gladiator school in Capua; The fugitives managed to capture carts with weapons for the gladiators. They settled on the Vesuvius volcano, where slaves who had fled from the surrounding estates began to flock. Soon their detachment reached 10 thousand people. Spartak, a most talented organizer and commander, was elected leader. When a detachment of three thousand under the command of Clodius marched against the slaves, occupying the approaches to Vesuvius, Spartacus’ warriors wove ropes from vines and unexpectedly descended along them from an impregnable steep slope to Clodius’s rear, from where they dealt him a crushing blow. New victories allowed Spartak to take possession of a large part of southern Italy. In 72 BC. e., already having 200 thousand people, he moved north. Armies under the command of both Roman consuls were sent against the rebels. Spartacus defeated them and reached the city of Mutina in northern Italy.

Interior view of the Roman Colosseum. The service premises for gladiators and cages for wild animals located under the arena are visible.

Some historians believe that Spartacus sought to cross the Alps and lead slaves to lands still free from the Roman yoke. Others believe that he intended, increasing his army even more, to march on Rome. And indeed, although the path to the Alps was open from Mutina, and the Roman government did not yet have the forces to block Spartacus’ path to the north, he turned south again. He planned to go through all of Italy, attracting new rebels, then cross on pirate ships to Sicily and raise numerous slaves there. Meanwhile, the government managed to assemble an army, headed by Crassus, a prominent politician and the richest man in Rome. With cruel punishments, resorting to decimation - the execution of every tenth soldier in units that turned out to be unstable, Crassus restored discipline in his troops. Moving after Spartacus, he pushed the rebels back to the Bruttian Peninsula. They found themselves between the sea and the Roman army. The pirates deceived Spartacus, did not provide ships and thwarted the plan to cross to Sicily. In a heroic outburst, Spartacus managed to break through the fortifications of Crassus into Lucania. Here the last battle with Crassus took place. Spartacus was killed and his army was destroyed. Thousands of rebels were crucified on crosses. Only a few escaped; they continued to fight for several more years and were eventually killed. V.I. Lenin called Spartacus one of the most outstanding heroes of one of the largest slave uprisings. Why couldn't the slaves win? A victorious revolution is possible only when the existing method of production has already become obsolete, when it is replaced by a new, more advanced one. The slave-owning mode of production was then in its prime and was still developing. The slaves did not have any program for the reconstruction of society. Rome was at the height of its military and political power. And although there was a sharp struggle between the Roman poor and the rich nobility (see article “Struggle for land in Ancient Rome”), rural slaves did not find allies among Roman citizens. The uprisings of rural slaves, on whose labor the main branch of the Roman economy was based, frightened not only the rich, but also the poor. Finally, the slaves themselves, placed outside the law, outside the society of citizens, disunited, without any organization, natives of different countries, could not recognize themselves as a single class.

Gladiators. Roman mosaic.

After the death of Spartacus, Rome no longer saw major slave uprisings. But the slaves never stopped their struggle, which took place in different forms. Repression against slaves intensified at the end of the 1st century. BC e., when, after civil wars, the sole ruler of the state in 27 BC. e. became Emperor Augustus. Under him, slaves who escaped during civil wars were executed or returned to their masters; on pain of death, slaves were forbidden to enlist in military units, which was sometimes allowed during civil wars. A law was passed: if a master was killed, all the slaves of the murdered man who were under the same roof or within shouting distance were tortured and executed for not coming to the rescue. “For,” the law said, “a slave must put the life and good of the master above his own.”

The events of the last years of the republic showed that individual masters were no longer powerless to resist the slaves. With the establishment of the empire, the state took upon itself the function of suppressing them. At the same time, fearing the protests of slaves driven to despair, the emperors were forced to increasingly limit the arbitrariness of their masters. Slaves of particularly cruel masters could ask imperial officials to be forcibly sold to more humane owners. The masters were deprived of the right to kill slaves, give them to gladiators and mines, and constantly keep them in ergastuls and shackles. From now on, only the court could impose such punishments.

In the 1st century BC e.-I century n. e. Agriculture and crafts in Italy reached a very high level. However, the heyday of slave production was short-lived. Despite all the efforts of the owners, the productivity of slave labor increased little. Slaves still hated their masters, killed them on occasion, joined bands of robbers, fled beyond the borders of the empire, and went over to its enemies. “Agility and intelligence are in the slave,” wrote the 4th century agronomist. n. e. Palladium, “are always close to disobedience and malicious intent, while stupidity and slowness are always close to good nature and humility.” And another agronomist of the 1st century AD. - Columella, advising not to spare 8,000 sesterces to buy a learned winegrower, notes that such winegrowers, due to their more lively minds and obstinacy, have to be kept in ergastuli at night and driven out to work in stocks. Slaves could not be forced to work with the care dictated by agronomic experience. Agriculture stopped progressing. The same Columella wrote: “The point is not in heavenly wrath, but in our guilt. We hand over agriculture like an executioner to the most worthless of slaves.”

The larger the estate, the more difficult it was to keep track of the slaves, so large farms - latifundia - fell into decline earlier than others. It is not surprising that in the II-III centuries. n. e. Vast expanses of land in the latifundia remained uncultivated and fell into disrepair.

Life forced the slave owners themselves to change the living and working conditions of slaves not only in crafts, but also in agriculture. To interest a slave in the results of his labor, landowners often allocated him his own farm - peculium, which included land, tools of production, and sometimes other slaves. Formally, the master remained the owner of the peculium, but the slave, the owner of the peculium, gave him only part of the product, saving the rest for his family. Even more often, the slave was released free of charge or for a ransom, but with the intention that the freed person would work for the master part of the time. In the II-III centuries. n. e. Most of the land in the latifundia was divided into small plots, leased to slaves, freedmen and freemen. Such tenants were called colones. Large workshops were also split into parts and rented out.

By the end of the Roman Empire, slaves did not disappear, but were pushed into the background by the colonists. At the same time, the colons became increasingly dependent on the landowner, and at the beginning of the 4th century. n. e. they were attached to the ground. And regardless of whether the colon (holder of the plot, planted on the land) was a slave or freeborn, he was sold along with his plot.

Colonies now became the main participants in the class struggle. They raised uprisings that lasted from the 3rd to the 5th centuries. n. e. By weakening the empire, these uprisings made it easier for the peoples neighboring the empire to defeat it.

Colonies were already the predecessors of medieval serfs. With the crisis of the slave-owning mode of production, new feudal relations arose (for more information on this, see the article “Europe at the turn of antiquity and the Middle Ages”). Slavery, which initially contributed to the flourishing of agriculture, crafts, political power and culture of Rome, ultimately, due to irreconcilable contradictions between slaves and slave owners, led to the final decline and death of the Roman state.

Development of slavery in Rome. Land concentration and formation of latifundia. From the second half of the 2nd century. BC. The period of the highest development of the slave-owning mode of production in Roman society begins. The wars of conquest that the Romans waged for about 120 years in the western and then eastern Mediterranean basin contributed to the influx of huge masses of slaves into the slave markets. Even during the first Punic War, the capture of Agrigentum (262) gave the Romans 25 thousand prisoners, who were sold into slavery. Six years later, the consul Regulus, having defeated the Carthaginians at Cape Ecnome (256), sent 20 thousand slaves to Rome. In the future, these numbers are steadily growing. Fabius Maximus, during the capture of Tarentum in 209, sold 30 thousand inhabitants into slavery. In 167, during the defeat of the cities of Enira by the consul Aemilius Paulus, 150 thousand people were sold into slavery. The end of the III Punic War (146) was marked by the sale into slavery of all the inhabitants of the destroyed Carthage. Even these fragmentary, scattered and, apparently, not always accurate figures given by Roman historians give an idea of the many thousands of slaves who poured into Rome.

The enormous quantitative growth of slaves led to qualitative changes in the socio-economic structure of Roman society: to the predominant importance of slave labor in production, to the transformation of the slave into the main producer of Roman society. These circumstances marked the complete victory and flowering of the slave-owning mode of production in Rome.

But the predominance of slave labor in production inevitably led to the displacement of the small free producer. Since Italy at this time continued to maintain the character of an agrarian country, here this process, first of all, most clearly unfolded in the field of agricultural production, and it consisted of two inextricably linked phenomena: the concentration of land and the formation of large slaveholding estates (so called latifundia) and at the same time the dispossession and pauperization of the peasantry.

Before 2nd century BC In Italian agriculture, small and medium-sized farms predominated, distinguished by their natural character and based mainly on the labor of free producers. As slavery developed in Rome, these farms began to be replaced by farms of a completely different type, based on a system of mass exploitation of slave labor and producing products not only to satisfy their own needs, but also for sale. The Roman historian Appian depicts this process as follows: “The rich, having occupied most of this undivided land and, due to the long-standing seizure, hoping that it would not be taken away from them, began to annex neighboring plots of the poor to their possessions, partly buying them for money, partly taking them away by force, so in the end, instead of small estates, they ended up with huge latifundia in their hands to cultivate the fields and guard the herds, they began to buy slaves..." (10:52)

Such an economy, designed for the development of commodity production and based on the exploitation of slave labor, is an exemplary villa, described by the famous Roman statesman Cato the Elder in his special work “On Agriculture.” Cato describes an estate with a complex economy: an oil grove of 240 yugers (60 hectares), a vineyard of 100 yugers (25 hectares), as well as grain farming and pasture for livestock. The organization of labor on such an estate is based, first of all, on the exploitation of slaves. Cato points out that at least 14 slaves are required to care for a vineyard of 100 jugeras, and 11 slaves for an olive garden of 240 jugeras. Cato gives detailed advice on how to more rationally exploit the labor of slaves, recommending keeping them busy on rainy days, when work is being done in the fields, and even on religious holidays. At the head of the management of the estate is a vilik, chosen from among the most devoted and knowledgeable slaves in agriculture; the vilik’s wife performs the duties of a housekeeper and cook.

Cato is extremely interested in the question of the profitability of individual branches of agriculture. “If they ask me,” he writes, “which estates should be put in first place, I will answer this way: in first place should be put a vineyard that produces wine of good quality and in abundance, in second place - an irrigated vegetable garden, in third - a willow planting ( for weaving baskets), on the fourth - an olive grove, on the fifth - a meadow, on the sixth - a grain field, on the seventh - a forest." From these words it is clear that grain crops, which were predominant in the old type of farms, are now retreating far back in comparison with the more profitable branches of agriculture (horticultural crops and livestock breeding).

Thus, the problem of the marketability of the economy during the time of Cato comes to the fore. It is no coincidence that, when considering the issue of purchasing an estate, Cato immediately gives advice to pay attention not only to the fertility of the soil, but also to the fact that “there is a significant city, sea, navigable river or good road nearby,” meaning the transportation and sale of products. “The owner should strive,” says Cato, “to sell more and buy less.”

Cato describes in his work a medium-sized estate, typical of an average one. Italy. But in the south of Italy, as well as in Sicily and Africa, huge latifundia arose, numbering hundreds and thousands of jugers. They were also based on the exploitation of slave labor on a massive scale and pursued the goal of increasing the profitability of agriculture.

The downside of the process of development of the latifundia, as already mentioned, was the dispossession and ruin of the peasantry. From the above words of Appian it is clear that small and medium-sized peasant farms perished not so much as a result of the economic competition of latifundial estates, but as a result of the seizure of land by large slave owners. The continuous wars of the 3rd-2nd centuries, waged on the territory of Italy, also had a destructive effect on peasant farms. During the war with Hannibal, according to some sources, about 50% of all peasant estates in central and southern Italy were destroyed. Long campaigns in Spain, Africa, and Asia Minor, tearing peasants away from their farms for a long time, also contributed to the decline of small and medium-sized landownership in Italy. (12;102)

Landless peasants partially turned into tenants or hired laborers, agricultural workers. But since they resorted to hiring the latter only during times of need (rest, harvest, grape harvest, etc.), the farm laborers could not count on any secure and constant income. Therefore, huge masses of peasants poured into the city. A minority of them took up productive work, that is, they turned into artisans (bakers, cloth makers, shoemakers, etc.) or construction workers, some took up petty trade.

But the overwhelming majority of these ruined people could not find permanent work. They led the lives of vagabonds and beggars, filling the forum and market squares. They did not disdain anything in search of casual income: selling votes in elections, false testimony in courts, denunciations and theft - and turned into a declassed layer of the population, into the ancient proletariat. They lived at the expense of society, lived on the pitiful handouts that they received from the Roman rich or political adventurers seeking popularity; and then through government distributions; ultimately, they lived off the barbaric exploitation of slave labor.

These are the most significant changes in the Roman economy and social life of the Roman state in the 2nd century. BC. However, the picture of these changes will be far from complete if we do not dwell on the development of trade and money-usury capital in Rome.

Development of trade and money-usury capital. The transformation of Rome into the largest Mediterranean power contributed to the widespread development of foreign trade. If the needs of the Roman population for handicraft items were mainly satisfied by local small industry, then agricultural products were imported from the western provinces, and luxury goods from Greece and the countries of the Hellenistic East. He played an outstanding role in world trade in the 3rd century. BC. Rhodes, after the fall of Corinth, Delos emerged as the largest trading center, which soon attracted not only all Corinthian, but also Rhodian trade. On Delos, where merchants from different countries met, trade and religious associations of Italian merchants, mainly Campanian Greeks, arose (they were “under the patronage” of one or another deity). (14;332)

Roman conquests ensured a continuous influx of valuables and monetary capital into Rome. After the first Punic War, the Roman treasury received 3,200 talents of indemnity (1 talent = 2,400 rubles). The indemnity imposed on the Carthaginians after the Second Punic War was equal to 10,000 talents, and on Antiochus III after the end of the Syrian War, 15,000 talents. The military spoils of the victorious Roman generals were colossal. Plutarch describes the triumphal entry into Rome of the victor at Pydna, Aemilius Paulus. The triumph lasted three days, during which captured works of art, precious weapons, and huge vessels filled with gold and silver coins were continuously carried and transported on chariots. In 189, after the Battle of Magnesia, the Romans captured as war booty 1,230 elephant tusks, 234 gold wreaths, 137,000 pounds of silver (1 Roman pound = 327 g), 224,000 Greek silver coins, 140,000 Macedonian gold coins, a large number products made of gold and silver. Up to the 2nd century. Rome experienced a certain shortage of silver coins, but after all these conquests, especially after the development of the Spanish silver mines, the Roman state was fully able to provide the silver basis for its monetary system.

All these circumstances led to the extremely widespread development of monetary and usurious capital in the Roman state. One of the organizational forms of development of this capital were companies of tax farmers, which farmed out various types of public works in Italy itself, as well as, and mainly, farmed out taxes in the Roman provinces. They were also engaged in credit and usury operations, especially widely in the provinces, where laws and customs supporting the sale into slavery for debts remained in force and where the loan interest was almost unlimited and reached 48-50%. Since representatives of the Roman equestrian class were engaged in trade, taxation and usury operations, they turn into a new layer of the Roman slave-owning nobility, into a trading and monetary aristocracy.

Such significant changes in the economy and social life of Rome confirm the idea that the Riga slave-owning society was moving to a new, higher stage of its development, which K. Marx defined as “... a slave-owning system aimed at the production of surplus value.” This definition reveals the true nature and historical significance of the phenomena discussed above: the victory of the slave-owning mode of production and the transformation of the slave into the main producer, the development of commodity production, the growth of trade and money-usurious capital, as well as the formation of new social strata of the Roman slave-owning society - the ancient lumpenproletariat, with one on the other hand, and the layer of the trading and monetary aristocracy (horsemen), on the other.

Bourgeois falsifiers of history, starting from the “patriarchs of modernization” of the ancient world, Mommsen and Ed. Meyer and up to their modern epigones, persistently talk about the development of capitalism in ancient Rome. Seizing on purely external analogies, they talk about the presence of capitalist forms of economy, about the “banking system,” about the formation of the capitalist class and the proletariat. However, all these statements, which are ultimately an apology for the capitalist system, do not stand up to serious criticism. Modernizers of ancient history ignore the question of the method of production, ignore the basic fact that in the slave-owning mode of production, in which the basis of production relations is the slave owner’s ownership of the means of production, as well as the production worker, i.e., the slave, the latter’s labor power is not sold and not bought, i.e., is not a product. Consequently, the basis of the slave-owning mode of production is a non-economic, natural method of appropriation of labor power, which distinguishes this method of production in principle and quite clearly from the capitalist mode of production. (24;98)

Marx repeatedly emphasized that “events that are strikingly similar, but occurring in different historical circumstances, lead to completely different results.” Thus, speaking about the influence of trade and merchant capital on ancient society, Marx specifically notes that due to the dominance of a certain method of production, it “... constantly results in a slave economy.” J.V. Stalin in his work “Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR” wrote: “They say that commodity production, under all conditions, should and will definitely lead to capitalism. This is not true.” And further: “Commodity production is older than capitalist production. It existed under the slave system and served it, but did not lead to capitalism.”

This is the true essence and historical significance of the changes that occurred in the economy of Roman slave society in the 2nd century. BC.

The crisis of the political forms of the Roman Republic. The profound processes and fundamental changes that occurred in the economic basis of Roman slave society could not but influence the political relationships and forms of government of the ancient Romans. The political superstructure of Roman society no longer corresponds to its economic basis - it becomes conservative and hinders its development. This circumstance should inevitably lead to a crisis of the political superstructure, to a crisis of the old forms and institutions of the Roman slave-owning republic. Moreover, this circumstance should inevitably lead to the replacement of the old political superstructure with new political and legal institutions that correspond to the changed basis and actively contribute to its formalization and strengthening.

The political superstructure of the Roman slave society, i.e. The republican forms of the Roman state arose and took shape at a time when Rome was a typical city-state, resting entirely on a natural economic system. It met the interests and needs of a relatively small community of citizens, built on primitive foundations. Now, when Rome has become a great Mediterranean power, when profound changes have occurred in the economic basis of Roman society and, above all, the slave-owning mode of production has triumphed, the old political forms, the old republican institutions turned out to be unsuitable and no longer meeting the needs and interests of the new social classes.

The provincial system of government developed gradually and largely spontaneously. There were no general legislative provisions relating to the provinces. Each new ruler of a province, upon taking office, usually issued an edict in which he determined what principles he would be guided by in governing the province. As rulers or governors of provinces, the Romans sent first praetors, and then high magistrates, at the end of their term of office in Rome (proconsul, propraetor). The governor was appointed to govern the province, as a rule, for a year and during this period he not only personified the fullness of military, civil and judicial power in his province, but in fact did not bear any responsibility for his activities before the Roman authorities. Residents of the provinces could complain about his abuses only after he handed over his affairs to his successor, but such complaints were rarely successful. Thus, the activities of the governors in the provinces were uncontrolled; the management of the provinces was actually handed over to them “at the mercy of”.

Almost all provincial communities were subject to direct and sometimes indirect taxes (mainly customs duties). The maintenance of provincial governors, their staff, as well as Roman troops stationed in the provinces also fell on the shoulders of the local population. But the activities of Roman publicans and moneylenders were especially devastating for the provincials. Companies of publicans, who took charge of collecting taxes in the provinces, contributed predetermined amounts to the Roman treasury, and then extorted them with huge surpluses from the local population. The predatory activities of publicans and moneylenders ruined entire countries that had once flourished, and reduced the inhabitants of these countries to the status of slaves, sold into slavery for debts. (16;77)

Such was the system that led to the predatory exploitation of the conquered regions, which could no longer meet the interests of the ruling class as a whole, but which was a consequence of the complete unsuitability and obsolescence of the state apparatus of the Roman Republic. Of course, in the Roman slave-owning society, with any change in its political superstructure, the state apparatus could not be replaced by a completely perfect apparatus, i.e., in other words, it was impossible to create a strong centralized empire due to the lack of a single economic base, due to the natural at its core slave farming. As is known, the largest empires of antiquity could only rise to the level of temporary and fragile military-administrative associations. The development of the Roman state was directed toward the creation of such a unification at the time under review, but even to achieve this goal there were no real conditions as long as too large and irreconcilable a gap continued to exist between the renewed economic basis of the Roman slave society and its dilapidated, conservative political superstructure. This gap made inevitable the crisis of the old political forms, that is, the crisis of the Roman Republic.

Class struggle in Roman society in the 2nd century. BC. However, replacing the outdated government system of the Roman Republic with some new one could not happen in a painless and peaceful way. Behind the old, dilapidated political forms there were certain classes, certain social groups with their narrow class interests, but no less fiercely defended by them. The old political superstructure could not be removed easily and peacefully; on the contrary, it steadfastly and actively resisted. Therefore, the crisis of the Roman Republic was accompanied by an extreme aggravation of the class struggle in Rome for several decades.

Roman society until the 2nd century. BC. presented a motley picture of warring classes and estates. Within the free population there was an intense struggle between the class of large slave owners and the class of small producers, represented in Rome primarily by the rural plebs. It was basically a struggle for land. Within the slave-owning class itself there was a struggle between the agricultural nobility (nobility) and the new trading and monetary aristocracy (equestrianism). In this era, the horsemen were already beginning to strive for an independent political role in the state and in this struggle against the politically omnipotent nobility sometimes blocked with the rural, and then with the urban plebs. By this time, the urban plebs were turning into a political and social force that, although it had no independent significance, could, as an ally or an enemy, have a decisive influence on tilting the needle of the political scales in a certain direction. All these complex, often intertwined lines of struggle are reflected in the turbulent political events of the period of crisis and fall of the republic, from the Gracchi movement to the years of civil wars.