Great Northern Expedition (1733–1743). The purpose and objectives of the second Kamchatka expedition The first Kamchatka Bering expedition on the map

Introduction

On April 28, 1732 (280 years ago), a decree was issued on the organization of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, under the leadership of V.I. Bering and A.I. Chirikov, signed by Empress Anna Ioannovna. A targeted study of the heritage of expeditionary research of those years is very relevant today. Information from the 18th century is of great interest, since it refers to a time period characterized by the greatest degree of preservation of the nature of the regions and the traditional culture of the peoples, reflected in documentary sources collected by the expedition members.

The purpose of the abstract: to study the geographical research of the Second Kamchatka Expedition of 1733-1743.

Based on the goal, we have identified the following tasks:

1. get acquainted with the biographies of outstanding participants of the Second Kamchatka Expedition

2. trace the route of the expedition and identify its most important discoveries

3. determine the geographical significance of the expedition

When writing the abstract, we used materials from the library of the Voronezh State Pedagogical University.

Expedition equipment. Participants

The purpose and objectives of the Second Kamchatka Expedition

The Admiralty Board was not entirely satisfied with the results of Bering's first expedition. She agreed that in the place where Bering sailed there was no connection, or, as they said then, similarity between the “Kamchatka land” and America, but the isthmus between Asia and the New World could be located to the north. In addition, the Senate indicated (September 13, 1732) that no astronomical observations had been made and no detailed information had been collected about “the local peoples, customs, fruits of the earth, metals and minerals.” Therefore, according to the opinion of the Senate, it was necessary to explore the North Sea against the mouth of the Kolyma, and from here sail to Kamchatka. It is clear that the Senate was not sure of the existence of a strait between Asia and America (Fig. 1).

Bering himself was aware that his voyage of 1728 did not completely solve the problems assigned to him. Immediately upon returning to St. Petersburg, already in April 1730, he submitted a project for a new expedition. In this project, he proposed to build a ship in Kamchatka and try to explore the coast of America on it, which, according to Bering’s proposals, “is not very far from Kamchatka, for example, 150 or 200 miles.” As an argument in favor of this opinion, Bering cited the following considerations: “by searching out, he invented” (i.e., discovered). Finally, Bering pointed out the need to explore the shores of Siberia from the Ob to the Lena.

On April 17, 1732, a decree was issued to equip a new expedition to Kamchatka under the command of Bering. The Senate, the Admiralty Board and the Academy of Sciences took part in condemning the expedition plan. Astronomer Joseph Delisle was commissioned to draw a map of Kamchatka and surrounding countries. Bering's first expedition did not bring data that would resolve the question of how far America is from Asia.

In 1732, Joseph Delisle compiled a map of “the lands and seas located north of the South Sea” for the leadership of the expedition. This map shows the non-existent “Land that Don Juan de Gama saw” south of Kamchatka and east of the “Land of Ieso.” In confirmation of the reality of this Earth, Delisle refers to the above-predicted data from Bering about the location of the land east of Kamchatka. Meanwhile, Bering's message referred to the Commander Islands, which had not yet been discovered at that time. Be that as it may, Delisle recommended looking for Gama Land "at noon" from Kamchatka, east of the so-called Company Land, found by the Dutch in 1643. Regarding this Land of Gama, Delisle speculates whether it connects with America in the California region. How Delisle imagined the land of Gama can be seen from the map he published in Paris in 1752. Delisle's incorrect map was the cause of many failures of Bering's expedition.

According to Bering's project, the second expedition was supposed to reach Kamchatka by land, through Siberia, like the first. It should be noted, however, that the President of the Admiralty Board, Admiral Nikolai Fedorovich Golovin, made a proposal to carry out an expedition to Kamchatka by sea - around South America, past Cape Horn and Japan; Golovin even undertook to become the head of such an enterprise. But his project was not accepted, and the first Russian circumnavigation was carried out only in 1803-1806 under the command of Krusenstern and Lisyansky, who chose exactly the route to Kamchatka that was suggested by Golovin, past Cape Horn.

According to the instructions of the Senate (decree of December 28, 1732), one of the goals of the expedition was to find out whether there is a connection between Kamchatka land and America, and whether there is a passage through the North Sea, i.e. Is it possible to travel by sea from the mouth of the Kolyma to the mouth of Anadyr and Kamchatka? If it turns out that Siberia is connected to America and it is impossible to pass, then find out whether the Midday or Eastern Sea is far on the other side of the earth, and then, as we said, return to Yakutsk through the Lena.

Another goal set by the Senate was to search the American coasts and find a route to Japan; in addition, it was necessary to describe the Ud River and the shore of the mouth of the Udi River to the Amur. The same decree ordered Bering, in accordance with the plans of Peter I, to reach which city or town of European possessions. The closest European possession at that time was the Spanish colony of Mexico. However, Chirikov, in his thoughts on the decree of December 28, 1732, did not advise sailing to Mexico: it would be more expedient, he wrote, to explore the unknown shores of America north of Mexico, 65 and 50 north latitudes. Partly for this reason, and partly out of fear of complications with Spain, the Admiralty Board, at its meeting on February 16, 1733, considering Bering’s instructions, determined that, in its opinion, there is no reasoning for the importance or need to be in the aforementioned European possessions. for those places are already known and marked on maps, and, moreover, the American coasts to 40 degrees north latitude or higher were examined from some Spanish ships.

Thus, the expedition was given purely geographical tasks - to find out whether there was a strait between Asia and America, and also to map the shores of northwestern America.

Expedition members

Bering was appointed head of the expedition, Chirikov was appointed as his assistant, and Shpanberg was appointed as his second assistant. The latter was intended as the head of a detachment for sailing to Japan; Subsequently, the Englishman Lieutenant Walton and the Dutchman Midshipman Shelting were assigned to him.

Among the navigators who participated in Bering's voyage, we note the names of Sven Waxel and Sofron Khitrov. They both left notes. For the inventory of the northern shores of Siberia, lieutenants Muravyov and Pavlov were identified, subsequently replaced by Malygin and Skuratov; Ovtsin, whose work was continued by Minin, then by Pronchishchev and Lasinius, who were replaced upon death by Khariton and Dmitry Laptev. The following were appointed from the Academy of Sciences: naturalist Johann Gmelin, then professor of history and geography Gerard Miller, later the famous historiographer, and finally professor of astronomy Louis Delisle de la Croyer; His assistants were students A.D. Krasilnikov, later a member of the Academy of Sciences, and Popov. Gmelin and Miller were subsequently replaced by Steller and I. Fisher. The study of Kamchatka was carried out by student Stepan Krasheninnikov, later an academician. Academicians received a salary of 1,260 rubles per year, and in addition, 40 pounds of flour annually. Each academician had 4 ministers. Students were entitled to a salary of 100 rubles per year, and 30 poods of flour. Hired blacksmiths and carpenters were paid 4 kopecks a day.

Gerard Friedrich (or in Russian Fedor Ivanovich) Miller was born in 1705 in Hereford, Germany. As a twenty-year-old youth, he was invited to serve at the St. Petersburg Academy with the rank of student. In 1733 he was assigned to the Bering expedition, in which he arrived, together with Gmelin, for 10 years. In Siberia, Miller worked in archives, making extracts from papers related to the history and geography of the region. In addition, he studied the life of the Buryats, Tungus, Ostyaks, and Voguls. Since the Siberian archives then mostly burned down, the materials collected by Miller represent a priceless treasure. Some of the documents were published in the Collection of State Charters and Treaties (1819 - 1828), Additions to Historical Acts in Monuments of Siberian History, in the 2nd edition of Miller's History of Siberia and in other places.

Doctor of Historical Sciences V. Pasetsky.

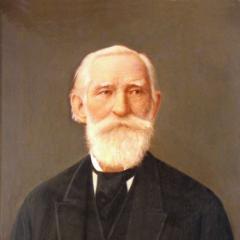

Vitus Ionassen (Ivan Ivanovich) Bering A681-1741) belongs to the number of great navigators and polar explorers of the world. The sea that washes the shores of Kamchatka, Chukotka and Alaska, and the strait that separates Asia from America bears his name.

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Bering stood at the head of the greatest geographical enterprise, the like of which the world did not know until the middle of the 20th century. The First and Second Kamchatka Expeditions, led by him, covered with their research the northern coast of Eurasia, all of Siberia, Kamchatka, the seas and lands of the northern part of the Pacific Ocean, and discovered the northwestern shores of America, unknown to scientists and navigators.

The essay about two Kamchatka expeditions of Vitus Bering, which we are publishing here, was written based on documentary materials stored in the Central State Archives of the Navy. These are decrees and resolutions, personal diaries and scientific notes of expedition members, ship logs. Many of the materials used have not been published before.

Vitus Beriag was born on August 12, 1681 in Denmark, in the city of Horsens. He bore the surname of his mother Anna Bering, who belonged to the famous Danish family. The navigator's father was a church warden. Almost no information has been preserved about Bering’s childhood. It is known that as a young man he took part in a voyage to the shores of the East Indies, where he had gone earlier and where his brother Sven spent many years.

Vitus Bering returned from his first voyage in 1703. The ship on which he sailed arrived in Amsterdam. Here Bering met with the Russian admiral Cornelius Ivanovich Cruys. On behalf of Peter I, Kruys hired experienced sailors for the Russian service. This meeting led Vitus Bering to serve in the Russian navy.

In St. Petersburg, Bering was appointed commander of a small ship. He delivered timber from the banks of the Neva to the island of Kotlin, where, by order of Peter I, a naval fortress was created - Kronstadt. In 1706, Bering was promoted to lieutenant. He had many responsible assignments: he monitored the movements of Swedish ships in the Gulf of Finland, sailed in the Sea of Azov, ferried the Pearl ship from Hamburg to St. Petersburg, and made a voyage from Arkhangelsk to Kronstadt around the Scandinavian Peninsula.

Twenty years passed in labor and battles. And then came a sharp turn in his life.

On December 23, 1724, Peter I gave instructions to the Admiralty Boards to send an expedition to Kamchatka under the command of a worthy naval officer.

The Admiralty Board proposed to put Captain Bering at the head of the expedition, since he “was in the East Indies and knows his way around.” Peter I agreed with Bering's candidacy.

On January 6, 1725, just a few weeks before his death, Peter signed instructions for the First Kamchatka Expedition. Bering was ordered to build two deck ships in Kamchatka or in another suitable place. On these ships it was necessary to go to the shores of the “land that goes north” and which, perhaps (“they don’t know the end of it”), is part of America, that is, to determine whether the land going north really connects with America.

In addition to Bering, naval officers Alexei Chirikov, Martyn Shpanberg, surveyors, navigators, and ship's foremen were appointed to the expedition. A total of 34 people went on the trip.

Petersburg was left in February 1725. The route lay through Vologda, Irkutsk, Yakutsk. This difficult campaign lasted for many weeks and months. Only at the end of 1726 the expedition reached the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk.

Construction of the vessel began immediately. The necessary materials were delivered from Yakutsk throughout the winter. This was associated with many difficulties.

On August 22, 1727, the newly built ship “Fortuna” and the small boat accompanying it left Okhotsk.

A week later, the travelers saw the shores of Kamchatka. Soon a strong leak opened in the Fortuna. They were forced to go to the mouth of the Bolshaya River and unload the ships.

Bering's reports to the Admiralty Board, preserved in the Central State Archives of the Navy, give an idea of the difficulties that travelers encountered in Kamchatka, where they stayed for almost a year before they could set sail again, further to the North.

“...Upon arrival at the Bolsheretsky mouth,” Bering wrote, “materials and provisions were transported to the Bolsheretsky fort by water in small boats. There are 14 courtyards in this fort of Russian housing. And he sent up the Bystraya River in small boats heavy materials and some of the provisions, which were transported by water to the Upper Kamchadal fort, 120 versts. And that same winter, they were transported from the Bolsheretsky fort to the Upper and Lower Kamchadal forts, completely according to local custom, on dogs. And every evening on the way for the night they raked out the snow for themselves, and covered it on top, because of the great blizzards, which in the local language are called blizzards. And if a blizzard catches a clean place, but they don’t have time to make a camp for themselves, then it covers people with snow, which is why “they die.”

On foot and on dog sleds they walked across Kamchatka more than 800 miles to Nizhne-Kamchatsk. The bot “St. Gabriel". On July 13, 1728, the expedition set sail again on it.

On August 11, they entered the strait that separates Asia from America and now bears the name of Bering. The next day, the sailors noticed that the land they were sailing past was left behind. On August 13, the ship, driven by strong winds, crossed the Arctic Circle.

Bering decided that the expedition had completed its task. He saw that the American coast was not connected to Asia, and was convinced that there was no such connection further to the north.

On August 15, the expedition entered the open Arctic Ocean and continued sailing to the north-northeast in fog. Many whales appeared. The vast ocean stretched all around. The land of Chukotka did not extend further to the north, according to Bering. America did not come close to the “Chukchi corner”.

The next day of sailing, too, there were no signs of the coast either in the west, or in the east, or in the north. Having reached 67°18"N latitude, Bering gave the order to return to Kamchatka, so as not to spend the winter on unfamiliar treeless shores “for no reason.” On September 2, “St. Gabriel” returned to the Lower Kamchatka harbor. Here the expedition spent the winter.

As soon as the summer of 1729 arrived, Bering set sail again. He headed east, where, according to Kamchatka residents, on clear days the land could sometimes be seen “across the sea.” During last year’s voyage, the travelers “didn’t happen to see her.” Berig decided to “find out for sure” whether this land really exists. Strong northern winds were blowing. With great difficulty, the navigators covered 200 kilometers, “but only saw no land,” Bering wrote to the Admiralty Board. The sea was enveloped in a “great fog,” and with it a fierce storm began. We set a course for Okhotsk. On the way back, Bering for the first time in the history of navigation went around and described the southern coast of Kamchatka.

On March 1, 1730, Bering, Lieutenant Shpanberg and Chirikov returned to St. Petersburg. The St. Petersburg Gazette published correspondence about the completion of the First Kamchatka Expedition of Vitus Bering. It was reported that Russian sailors on ships built in Okhotsk and Kamchatka ascended to the Polar Sea well north of 67° N. w. and thereby proved (“invented”) that “there is a truly northeastern passage there.” The newspaper further emphasized: “Thus, from Lena, if ice did not interfere in the northern country, it would be possible to travel by water to Kamchatka, and also further to Japan, Hina and the East Indies, and besides, it (Bering.- V.P.) and from the local residents I learned that before 50 and 60 years a certain ship from Lena arrived to Kamchatka.”

The first Kamchatka expedition made a major contribution to the development of geographical ideas about the northeastern coast of Asia, from Kamchatka to the northern shores of Chukotka. Geography, cartography and ethnography have been enriched with new valuable information. The expedition created a series of geographical maps, of which the final map is of particularly outstanding importance. It is based on numerous astronomical observations and for the first time gave a real idea not only of the eastern coast of Russia, but also of the size and extent of Siberia. According to James Cook, who named the Bering Strait between Asia and America, his distant predecessor “mapped the coast very well, determining the coordinates with an accuracy that would have been difficult to expect with his capabilities.” The first map of the expedition, which shows the areas Siberia in the area from Tobolsk to the Pacific Ocean, was reviewed and approved by the Academy of Sciences and was immediately used by Russian scientists and was soon widely distributed in Europe. In 1735, it was published in London, then again in France. And then this map was repeatedly republished as part of various atlases and books... The expedition determined the coordinates of 28 points along the route Tobolsk - Yeniseisk - Ilimsk - Yakutsk - Okhotsk-Kamchatka-Chukotsky Nose - Chukchi Sea, which were then included in the “Catalogue of Cities and Notables”. Siberian places, put on the map, through which the route was, what width and length they were.”

And Bering was already developing a project for the Second Kamchatka Expedition, which later turned into an outstanding geographical enterprise, the like of which the world had not known for a long time.

The main place in the program of the expedition, of which Bering was appointed head, was given to the study of all of Siberia, the Far East, the Arctic, Japan, and northwestern America in geographical, geological, physical, botanical, zoological, and ethnographic terms. Particular importance was attached to the study of the Northern Sea Passage from Arkhangelsk to the Pacific Ocean.

At the beginning of 1733, the main detachments of the expedition left St. Petersburg. More than 500 naval officers, scientists, and sailors were sent from the capital to Siberia.

Bering, together with his wife Anna Matveevna, went to Yakutsk to supervise the transfer of cargo to the port of Okhotsk, where five ships were to be built for sailing the Pacific Ocean. Bering monitored the work of the teams of X. and D. Laptev, D. Ovtsyn, V. Pronchishchev, P. Lassinius, who were engaged in the study of the northern coast of Russia, and the academic team, which included historians G. Miller and A. Fischer, naturalists I. Gmelin, S. Krasheninnikov, G. Steller, astronomer L. Delyakroer.

Archival documents give an idea of the unusually active and versatile organizational work of the navigator, who led from Yakutsk the activities of many detachments and units of the expedition, which conducted research from the Urals to the Pacific Ocean and from the Amur to the northern shores of Siberia.

In 1740, the construction of the packet boats “St. Peter" and "St. Pavel", on which Vitus Bering and Alexey Chirikov undertook the transition to Avachinskaya harbor, on the shore of which the Petropavlovsk port was founded.

152 officers and sailors and two members of the academic detachment went on the voyage on two ships. Bering assigned Professor L. Delyakroer to the ship “St. Pavel,” and took adjunct G. Steller to “St. Peter" to his crew. Thus began the path of a scientist who later gained worldwide fame.

On June 4, 1741, the ships went to sea. They headed southeast, to the shores of the hypothetical Land of Juan de Gama, which appeared on the map of J. N. Delisle and which was ordered to be found and explored along the way to the shores of northwestern America. Severe storms hit the ships, but Bering persistently moved forward, trying to accurately fulfill the Senate's decree. There was often fog. In order not to lose each other, the ships rang a bell or fired cannons. This is how the first week of sailing passed. The ships reached 47° N. sh., where the Land of Juan de Gama was supposed to be, but there were no signs of land. On June 12, travelers crossed the next parallel - no land. Bering ordered to go northeast. He considered his main task to be to reach the northwestern shores of America, which had not yet been discovered or explored by any navigator.

The ships had barely passed the first tens of miles north when they found themselves in dense fog. Packet boat "St. Pavel" under the command of Chirikov disappeared from sight. For several hours you could hear the bell ringing there, letting you know about your location, then the bell could no longer be heard, and deep silence lay over the ocean. Captain-Commander Bering ordered the cannon to be fired. There was no answer.

For three days Bering plowed the sea, as agreed, in those latitudes where the ships were separated, but never met the detachment of Alexei Chirikov.

For about four weeks the packet boat “St. Peter walked along the ocean, meeting only herds of whales along the way. All this time, storms mercilessly battered the lonely ship. Storms followed one after another. The wind tore the sails, damaged the spar, and loosened the fastenings. A leak appeared in some places in the grooves. The fresh water we had taken with us was running out.

“On July 17,” as recorded in the logbook, “from midday at half past one o’clock we saw land with high ridges and a hill covered with snow.”

Bering and his companions were impatient to land on the American coast they had discovered. But strong, variable winds blew. The expedition, fearing rocky reefs, was forced to stay away from the land and follow it to the west. Only on July 20 the excitement decreased and the sailors decided to lower the boat.

Bering sent naturalist Steller to the island. Steller spent 10 hours on the shore of Kayak Island and during this time managed to get acquainted with the abandoned dwellings of the Indians, their household items, weapons and remains of clothing, and described 160 species of local plants.

Late July to August “St. Peter walked now in the labyrinth of islands, now at a small distance from them.

On August 29, the expedition again approached the land and anchored between several islands, which were named Shumaginsky after the sailor Shumagin, who had just died of scurvy. Here the travelers first met the inhabitants of the Aleutian Islands and exchanged gifts with them.

September came, the ocean was stormy. The wooden ship could hardly withstand the onslaught of the hurricane. Many officers began to talk about the need to stay for the winter, especially as the air became increasingly cold.

The travelers decided to hurry to the shores of Kamchatka. More and more alarming entries appear in the logbook, indicating the difficult situation of the seafarers. Yellowed pages, hastily written by the officers on duty, tell how they sailed day after day without seeing land. The sky was overcast with clouds, through which a ray of sunlight did not break through for many days and not a single star was visible. The expedition could not accurately determine its location and did not know at what speed they were moving towards their native Petropavlovsk...

Vitus Bering was seriously ill. The illness was further intensified by dampness and cold. It rained almost continuously. The situation became more and more serious. According to the captain's calculations, the expedition was still far from Kamchatka. He understood that he would reach his native promised land no earlier than the end of October, and this only if the western winds changed to fair eastern ones.

On September 27, a fierce squall hit, and three days later a storm began, which, as noted in the logbook, created “great excitement.” Only four days later the wind decreased somewhat. The respite was short-lived. On October 4, a new hurricane hit, and huge waves again hit the sides of the St. for several days. Petra."

Since the beginning of October, most of the crew had already become so weak from scurvy that they could not take part in the ship's work. Many lost their arms and legs. Food supplies were dwindling catastrophically...

After enduring a severe storm that lasted many days, “St. Peter” again began, despite the headwind from the west, to move forward, and soon the expedition discovered three islands: St. Marcian, St. Stephen and St. Abraham.

The dramatic situation of the expedition worsened every day. Not only was there not enough food, but also fresh water. The officers and sailors who were still standing were exhausted by backbreaking work. According to navigator Sven Waxel, “the ship floated like a piece of dead wood, almost without any control and went at the will of the waves and wind, wherever they wanted to drive it.”

On October 24, the first snow covered the deck, but fortunately it did not last long. The air became more and more chilly. On this day, as noted in the logbook, there were “28 people of various ranks” who were sick.

Bering understood that the most crucial and difficult moment had arrived in the fate of the expedition. Himself, completely weakened by illness, he still went up on deck, visited the officers and sailors, and tried to raise faith in the successful outcome of the journey. Bering promised that as soon as land appeared on the horizon, they would certainly moor to it and stop for the winter. Team "St. Petra trusted her captain, and everyone who could move their legs, straining their last strength, corrected the urgent and necessary ship work.

On November 4, early in the morning, the contours of an unknown land appeared on the horizon. Having approached it, they sent officer Plenisner and naturalist Steller ashore. There they found only thickets of dwarf willow spreading along the ground. Not a single tree grew anywhere. Here and there on the shore lay logs washed up by the sea and covered with snow.

A small river flowed nearby. In the vicinity of the bay, several deep holes were discovered, which, if covered with sails, could be converted into housing for sick sailors and officers.

The landing has begun. Bering was carried on a stretcher to the dugout prepared for him.

The disembarkation was slow. Hungry, weakened by illness, sailors died on the way from ship to shore or as soon as they set foot on land. So 9 people died, 12 sailors died during the voyage.

On November 28, a strong storm tore the ship from its anchors and threw it ashore. At first, the sailors did not attach serious importance to this, since they believed that they had landed on Kamchatka and that the local residents would help the dogs to get to Petropavlovsk.

The group sent by Bering for reconnaissance climbed to the top of the mountain. From above, they saw that the vast sea spread out around them. They landed not in Kamchatka, but on an uninhabited island lost in the ocean.

“This news,” wrote Svei Vaksel, “impacted on our people like a thunderclap. We clearly understood what a helpless and difficult situation I found myself in, that we were threatened with complete destruction.”

During these difficult days, the illness tormented Bering more and more. He felt that his days were numbered, but continued to take care of his people.

The captain-commander lay alone in a dugout, covered with a tarpaulin on top. Bering suffered from the cold. His strength was leaving him. He could no longer move either his arm or his leg. The sand sliding from the walls of the dugout covered the legs and lower part of the body. When the officers wanted to dig it up, Bering objected, saying that it was warmer. In these last, most difficult days, despite all the misfortunes that befell the expedition, Bering did not lose his courage, he found sincere words to encourage his despondent comrades.

Bering died on December 8, 1741, unaware that the last refuge of the expedition was a few days away from Petropavlovsk.

Bering's companions survived a difficult winter. They ate the meat of sea animals, which were found here in abundance. Under the leadership of officers Sven Vaksel and Sofron Khitrovo, they built a new ship from the wreckage of the packet boat "St. Peter". On August 13, 1742, the travelers said goodbye to the island, which they named after Bering, and safely reached Petropavlovsk. There they learned that the packet boat “St. Pavel,” commanded by Alexey Chirikov, returned to Kamchatka last year, discovering, like Bering, the northwestern shores of America. These lands were soon named Russian America (now Alaska).

Thus ended the Second Kamchatka Expedition, whose activities were crowned with great discoveries and outstanding scientific achievements.

Russian sailors were the first to discover the previously unknown northwestern shores of America, the Aleutian ridge, the Commander Islands and crossed out the myths about the Land of Juan de Gama, which Western European cartographers depicted in the north of the Pacific Ocean.

Russian ships were the first to pave the sea route from Russia to Japan. Geographical science has received accurate information about the Kuril Islands and Japan.

The results of discoveries and research in the North Pacific Ocean are reflected in a whole series of maps. Many of the surviving members of the expedition took part in their creation. A particularly outstanding role in summarizing the materials obtained by Russian sailors belongs to Alexei Chirikov, one of the brilliant and skillful sailors of that time, Bering’s devoted assistant and successor. It fell to Chirikov to complete the affairs of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. He compiled a map of the North Pacific Ocean, which shows with amazing accuracy the path of the ship "St. Pavel,” the northwestern shores of America, the islands of the Aleutian ridge and the eastern shores of Kamchatka, discovered by sailors, which served as the starting base for Russian expeditions.

Officers Dmitry Ovtsyn, Sofron Khitrovo, Alexey Chirikov, Ivan Elagin, Stepan Malygin, Dmitry and Khariton Laptev compiled a “Map of the Russian Empire, the northern and eastern shores adjacent to the Arctic and Eastern oceans with part of the western American shores and islands newly found through sea voyage Japan."

Equally fruitful was the activity of the northern detachments of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, which were often separated into an independent Great Northern Expedition.

As a result of sea and foot voyages of officers, navigators and surveyors operating in the Arctic, the northern coast of Russia from Arkhangelsk to Bolshoy Baranov Kamen, located east of Kolyma, was explored and mapped. Thus, according to M.V. Lomonosov, the passage of the sea from the Arctic Ocean to the Pacific was “undoubtedly proven.”

To study the meteorological conditions of Siberia, observation points were created from the Volga to Kamchatka. The world's first experience of organizing a meteorological network over such a vast area was a brilliant success for Russian scientists and sailors.

On all ships of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, which sailed across the polar seas from Arkhangelsk to Kolyma, across the Pacific Ocean to Japan and northwestern America, visual and, in some cases, instrumental meteorological observations were carried out. They were included in the log books and have survived to this day. Today, these observations are of particular value also because they reflect the characteristics of atmospheric processes during years of extremely increased ice cover in the Arctic seas.

The scientific heritage of Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition is so great that it has not yet been fully mastered. It was and is now widely used by scientists in many countries.

The first Kamchatka expedition 1725-1730. occupies a special place in the history of science. She

was the first major scientific expedition in the history of the Russian Empire, undertaken by government decision. In organizing and conducting the expedition, a large role and credit belongs to the navy. The starting point of the First Kamchatka Expedition was the personal decree of Peter I on the organization of the “First Kamchatka Expedition” under the command of Vitus Bering, December 23, 1724. Peter I personally wrote instructions to Bering.

The sea route from Okhotsk to Kamchatka was discovered by the expedition of K. Sokolov and N. Treski in 1717, but the sea route from the Sea of Okhotsk to the Pacific Ocean had not yet been discovered. It was necessary to walk across the mainland to Okhotsk, and from there to Kamchatka. There, all supplies were delivered from Bolsheretsk to the Nizhnekamchatsky prison. This created great difficulties in the delivery of materials and supplies. It is difficult for us to even imagine the incredible difficulty of the journey across the deserted thousand-mile tundra for travelers who do not yet have organizational skills. It is interesting to see how the journey proceeded and in what form people and animals arrived at their destination. Here, for example, is a report from Okhotsk dated October 28: “Provisions sent from Yakutsk by dry route arrived in Okhotsk on October 25 on 396 horses. On the way, 267 horses disappeared and died due to lack of fodder. During the journey to Okhotsk, people suffered great hunger; due to lack of food, they ate belts,

leather and leather pants and soles. And the horses that arrived ate grass, getting out from under the snow; due to their late arrival in Okhotsk, they did not have time to prepare hay, but it was not possible; everyone was frozen from deep snow and frost. And the rest of the ministers arrived on dog sleds to Okhotsk.” From here the goods were transported to Kamchatka. Here, in the Nizhnekamchatsky fort, under the leadership of Bering, on April 4, 1728, a boat was laid down, which in June of the same year was launched and named “St. Archangel Gabriel.”

On this ship, Bering and his companions sailed through the strait in 1728, which was later named after the leader of the expedition. However, due to dense fog, it was not possible to see the American coast. Therefore, many decided that the expedition was unsuccessful.

Results of the First Kamchatka Expedition

Meanwhile, the expedition determined the extent of Siberia; the first sea vessel on the Pacific Ocean was built - “Saint Gabriel”; 220 geographical objects have been discovered and mapped; the existence of a strait between the continents of Asia and America has been confirmed; the geographical position of the Kamchatka Peninsula has been determined. The map of V. Bering's discoveries became known in Western Europe and was immediately included in the latest geographical atlases. After the expedition of V. Bering, the outlines of the Chukotka Peninsula, as well as the entire coast from Chukotka to Kamchatka, take on a form on maps that is close to their modern images. Thus, the northeastern tip of Asia was mapped, and now there was no doubt about the existence of a strait between the continents. The first printed report about the expedition, published in the St. Petersburg Gazette on March 16, 1730, noted that Bering reached 67 degrees 19 minutes north latitude and confirmed that “there is a truly northeastern passage there, so that from Lena ... by water to Kamchatka and further to Japan, Hina

(China) and the East Indies it would be possible to get there.”

Of great interest to science were the geographical observations and travel records of the expedition participants: A.I. Chirikova, P.A. Chaplin and others. Their descriptions of coasts, relief,

flora and fauna, observations of lunar eclipses, ocean currents, weather conditions, observations about earthquakes, etc. were the first scientific data on the physical geography of this part of Siberia. The descriptions of the expedition participants also contained information about the economy of Siberia, ethnography, and others.

The first Kamchatka expedition, which began in 1725 with the instructions of Peter I, returned to St. Petersburg on March 1, 1730. V. Bering presented to the Senate and the Admiralty Board a report on the progress and results of the expedition, a petition for promotion in rank and rewarding officers and privates.

Sources:

1. Alekseev A.I. Russian Columbuses. – Magadan: Magadan Book Publishing House, 1966.

2. Alekseev A.I. Brave sons of Russia. – Magadan: Magadan Book Publishing House, 1970.

3. Berg A. S. Discovery of Kamchatka and Bering’s expedition 1725-1742. – M.: Academy Publishing House

Sciences USSR, 1946.

4. Kamchatka XVII-XX centuries: historical and geographical atlas / Ed. ed. N. D. Zhdanov, B. P. Polevoy. – M.: Federal Service of Geodesy and Cartography of Russia, 1997.

5. Pasetsky V. M. Vitus Bering. M., 1982.

6. Polevoy B.P. Russian Columbuses. – In the book: Nord-Ost. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 1980.

7. Russian Pacific epic. Khabarovsk, 1979.

8. Sergeev V.D. Pages of the history of Kamchatka (pre-revolutionary period): educational and methodological manual. – Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky: Far Eastern book publishing house Kamchatka branch, 1992.

Second Kamchatka Expedition

Second Kamchatka Expedition

Russian map of the Far East (1745).

Second Kamchatka Expedition took place as part of the largest expedition in the history of mankind - the First Academic Expedition, in total about 3 thousand people took part. The leader of the First Academic Expedition is Miller. Vitus Bering's detachment was financed by the Russian Admiralty and pursued more military-strategic goals than scientific ones. The goals are to prove the existence of a strait between Asia and America and take the first steps towards the transition to the American continent. Returning to St. Petersburg from the First Kamchatka Expedition, Vitus Bering presented memos in which he expressed confidence in the comparative proximity of America to Kamchatka and in the advisability of establishing trade with the inhabitants of America. Having traveled through the whole of Siberia twice, he was convinced that it was possible to mine iron ore, salt and grow bread here. Bering put forward further plans to explore the northeastern coast of Russian Asia, exploring the sea route to the mouth of the Amur and the Japanese Islands - as well as to the American continent.

On June 4 - the year when Vitus Bering turned 60 years old - “St. Peter" under the command of Bering and "St. Pavel" under the command of Chirikov were the first Europeans to reach the northwestern shores of America. On June 20, in conditions of storm and thick fog, the ships lost each other. After several days of fruitless attempts to connect, the sailors had to continue their journey alone.

March of Saint Peter

"St. Peter" reached the southern coast of Alaska on July 17 in the area of the St. Elijah Ridge. By that time, Bering was already feeling unwell, so he did not even land on the shore to which he had been going for so many years. In the area of Kayak Island, the crew replenished fresh water supplies, and the ship began to move southwest, from time to time noticing individual islands (Montagyu, Kodiak, Tumanny) and groups of islands to the north. Progress against the headwind was very slow, one after another the sailors fell ill with scurvy, and the ship experienced a lack of fresh water.

At the end of August, “St. Peter” for the last time approached one of the islands, where the ship remained for a week and where the first meeting with the local residents - the Aleuts - took place. The first Bering sailor who died of scurvy, Nikita Shumagin, was buried on the island, in whose memory Bering named this island.

On September 6, the ship headed due west across the open sea, along the Aleutian Islands chain. In stormy weather, the ship drifted across the sea like a piece of wood. Bering was already too ill to control the ship. Finally, two months later, on November 4, high mountains covered with snow were noticed from the ship. By this time, the packet boat was practically uncontrollable and was floating “like a piece of dead wood.”

The sailors hoped that they had reached the shores of Kamchatka. In fact, it was only one of the islands of the archipelago, which would later be called the Commander Islands. "St. Peter dropped anchor not far from the shore, but was torn from his anchor by a wave and thrown over the reefs into a deep bay off the coast, where the waves were not so strong. This was the first happy accident in the entire period of navigation. Using it, the team managed to transport the sick, the remains of provisions and equipment to the shore.

Adjacent to the bay was a valley surrounded by low mountains, already covered with snow. A small river with crystal clear water ran through the valley. They had to spend the winter in dugouts covered with tarpaulin. Out of a crew of 75 people, thirty sailors died immediately after the shipwreck and during the winter. Captain-Commander Vitus Bering himself died on December 6. This island would later be named after him. A wooden cross was placed on the commander's grave.

In defiance of death

Image of Kamchatka from Krasheninnikov’s book (1755).

The surviving sailors were led by Vitus Bering's senior mate, Swede Sven Waxel. Having survived winter storms and earthquakes, the team was able to survive until the summer. They were again lucky that on the western shore there was a lot of Kamchatka forest washed up by the waves and fragments of wood that could be used as fuel. In addition, on the island it was possible to hunt arctic foxes, sea otters, sea cows, and, with the arrival of spring, fur seals. Hunting these animals was very easy, because they were not at all afraid of humans.

In the spring, construction began on a small single-masted ship from the remains of the dilapidated St. Peter." And again the team was lucky - despite the fact that all three ship carpenters died of scurvy, and there was no shipbuilding specialist among the naval officers, the team of shipbuilders was headed by Cossack Savva Starodubtsev, a self-taught shipbuilder, who was a simple worker during the construction of expeditionary packet boats in Okhotsk , and was later taken to the team. By the end of the summer, the new “St. Peter" was launched. It had much smaller dimensions: the length along the keel was 11 meters, and the width was less than 4 meters.

The surviving 46 people, in terrible cramped conditions, went to sea in mid-August, four days later they reached the coast of Kamchatka, and nine days later, on August 26, they reached Petropavlovsk.

For his, without exaggeration, feat, Savva Starodubtsev was awarded the title of son of a boyar. New gukor "St. Peter” went to sea for another 12 years, until, and Starodubtsev himself, having mastered the profession of a shipbuilder, built several more ships.

Memory

- In 1995, the Bank of Russia, in the series of commemorative coins “Exploration of the Russian Arctic”, issued a coin “Great Northern Expedition” in denomination of 3 rubles.

- In 2004, the Bank of Russia issued a series of commemorative coins “2nd Kamchatka Expedition” in denominations of 3, 25 and 100 rubles, dedicated to the expedition.

Literature and sources

- Vaksel Sven. Second Kamchatka expedition of Vitus Bering / Trans. from hand On him. language Yu. I. Bronstein. Ed. from previous A. I. Andreeva. - M.: Glavsevmorput, 1940. - 176 °C.;

- Magidovich I.P., Magidovich V.I., Essays on the history of geographical discoveries, vol. III. M., 1984

Notes

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

See what the “Second Kamchatka Expedition” is in other dictionaries:

The region in the Russian Far East covers the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Commander Islands. Formed in 1932, it includes the Koryak Autonomous District. district, adm. center - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Pl. 472.3 thousand km² (170.8 thousand excluding Koryak Autonomous Okrug).… … Geographical encyclopedia

Wiktionary has an article “expedition” An expedition is a journey with a specifically defined scientific or military purpose... Wikipedia

In Russian federation. 472.3 thousand km2. Population 396.5 thousand people (1998), urban 80.6%. Formed on October 20, 1932 as part of the Khabarovsk Territory; since 1956 an independent region. Includes Koryak Autonomous Okrug. 4 cities, 8 villages... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

- (“Second Kamchatka Expedition”, “Siberian-Pacific”, “Siberian”) a number of geographical expeditions undertaken by Russian sailors along the Arctic coast of Siberia, to the shores of North America and Japan in the second quarter of the 18th century.... ... Wikipedia

Russian map of the Far East (1745). The expedition of Bering Chirikov's detachment took place as part of the Great Northern Expedition. Vitus Bering's detachment was financed by the Russian Admiralty and pursued more military strategic goals rather than ... Wikipedia

1733 - 1743 - Second Kamchatka expedition of V. Bering... Timeline of World History: Dictionary

This term has other meanings, see Bering. Vitus Bering Vitus Bering Occupation: navigator, officer of the Russian fleet ... Wikipedia

This article is about the navigator. About his uncle, a Danish poet, see Bering, Vitus Pedersen Vitus Jonassen Bering (Danish Vitus Jonassen Bering; also Ivan Ivanovich; (1681 1741) navigator, officer of the Russian fleet, captain commander. By origin... ... Wikipedia

This article is about the navigator. About his uncle, a Danish poet, see Bering, Vitus Pedersen Vitus Jonassen Bering (Danish Vitus Jonassen Bering; also Ivan Ivanovich; (1681 1741) navigator, officer of the Russian fleet, captain commander. By origin... ... Wikipedia

Abstract on the topic:

Second Kamchatka Expedition

Introduction

April 1732 (280 years ago) a decree was issued on the organization of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, under the leadership of V.I. Bering and A.I. Chirikov, signed by Empress Anna Ioannovna. A targeted study of the heritage of expeditionary research of those years is very relevant today. Information from the 18th century is of great interest, since it refers to a time period characterized by the greatest degree of preservation of the nature of the regions and the traditional culture of the peoples, reflected in documentary sources collected by the expedition members.

Purpose of the abstract: to study the geographical research of the Second Kamchatka Expedition of 1733-1743.

Based on the goal, we have identified the following tasks:

.get acquainted with the biographies of outstanding participants of the Second Kamchatka Expedition

.trace the route of the expedition and identify its most important discoveries

.determine the geographical significance of the expedition

When writing the abstract, we used materials from the library of the Voronezh State Pedagogical University.

Chapter 1. Equipment of the expedition. Participants

1 The purpose and objectives of the Second Kamchatka Expedition

The Admiralty Board was not entirely satisfied with the results of Bering's first expedition. She agreed that in the place where Bering sailed there was no connection, or, as they said then, similarity between the “Kamchatka land” and America, but the isthmus between Asia and the New World could be located to the north. In addition, the Senate indicated (September 13, 1732) that no astronomical observations had been made and no detailed information had been collected about “the local peoples, customs, fruits of the earth, metals and minerals.” Therefore, according to the opinion of the Senate, it was necessary to explore the North Sea against the mouth of the Kolyma, and from here sail to Kamchatka. It is clear that the Senate was not sure of the existence of a strait between Asia and America (Fig. 1).

Bering himself was aware that his voyage of 1728 did not completely solve the problems assigned to him. Immediately upon returning to St. Petersburg, already in April 1730, he submitted a project for a new expedition. In this project, he proposed to build a ship in Kamchatka and try to explore the coast of America on it, which, according to Bering’s proposals, “is not very far from Kamchatka, for example, 150 or 200 miles.” As an argument in favor of this opinion, Bering cited the following considerations: “by searching out, he invented” (i.e., discovered). Finally, Bering pointed out the need to explore the shores of Siberia from the Ob to the Lena.

In April 1732, a decree was issued to equip a new expedition to Kamchatka under the command of Bering. The Senate, the Admiralty Board and the Academy of Sciences took part in condemning the expedition plan. Astronomer Joseph Delisle was commissioned to draw a map of Kamchatka and surrounding countries. Bering's first expedition did not bring data that would resolve the question of how far America is from Asia.

In 1732, Joseph Delisle compiled a map of “the lands and seas located north of the South Sea” for the leadership of the expedition. This map shows the non-existent “Land that Don Juan de Gama saw” south of Kamchatka and east of the “Land of Ieso.” In confirmation of the reality of this Earth, Delisle refers to the above-predicted data from Bering about the location of the land east of Kamchatka. Meanwhile, Bering's message referred to the Commander Islands, which had not yet been discovered at that time. Be that as it may, Delisle recommended looking for Gama Land "at noon" from Kamchatka, east of the so-called Company Land, found by the Dutch in 1643. Regarding this Land of Gama, Delisle speculates whether it connects with America in the California region. How Delisle imagined the land of Gama can be seen from the map he published in Paris in 1752. Delisle's incorrect map was the cause of many failures of Bering's expedition.

According to Bering's project, the second expedition was supposed to reach Kamchatka by land, through Siberia, like the first. It should be noted, however, that the President of the Admiralty Board, Admiral Nikolai Fedorovich Golovin, made a proposal to carry out an expedition to Kamchatka by sea - around South America, past Cape Horn and Japan; Golovin even undertook to become the head of such an enterprise. But his project was not accepted, and the first Russian circumnavigation was carried out only in 1803-1806 under the command of Krusenstern and Lisyansky, who chose exactly the route to Kamchatka that was suggested by Golovin, past Cape Horn.

According to the instructions of the Senate (decree of December 28, 1732), one of the goals of the expedition was to find out whether there is a connection between Kamchatka land and America, and whether there is a passage through the North Sea, i.e. Is it possible to travel by sea from the mouth of the Kolyma to the mouth of Anadyr and Kamchatka? If it turns out that Siberia is connected to America and it is impossible to pass, then find out whether the Midday or Eastern Sea is far on the other side of the earth, and then, as we said, return to Yakutsk through the Lena.

Another goal set by the Senate was to search the American coasts and find a route to Japan; in addition, it was necessary to describe the Ud River and the shore of the mouth of the Udi River to the Amur. The same decree ordered Bering, in accordance with the plans of Peter I, to reach which city or town of European possessions. The closest European possession at that time was the Spanish colony of Mexico. However, Chirikov, in his thoughts on the decree of December 28, 1732, did not advise sailing to Mexico: it would be more expedient, he wrote, to explore the unknown shores of America north of Mexico, 65 and 50 north latitudes. Partly for this reason, and partly out of fear of complications with Spain, the Admiralty Board, at its meeting on February 16, 1733, considering Bering’s instructions, determined that, in its opinion, there is no reasoning for the importance or need to be in the aforementioned European possessions. for those places are already known and marked on maps, and, moreover, the American coasts to 40 degrees north latitude or higher were examined from some Spanish ships.

Thus, the expedition was given purely geographical tasks - to find out whether there was a strait between Asia and America, and also to map the shores of northwestern America.

2 Expedition members

Bering was appointed head of the expedition, Chirikov was appointed as his assistant, and Shpanberg was appointed as his second assistant. The latter was intended as the head of a detachment for sailing to Japan; Subsequently, the Englishman Lieutenant Walton and the Dutchman Midshipman Shelting were assigned to him.

Among the navigators who participated in Bering's voyage, we note the names of Sven Waxel and Sofron Khitrov. They both left notes. For the inventory of the northern shores of Siberia, lieutenants Muravyov and Pavlov were identified, subsequently replaced by Malygin and Skuratov; Ovtsin, whose work was continued by Minin, then by Pronchishchev and Lasinius, who were replaced upon death by Khariton and Dmitry Laptev. The following were appointed from the Academy of Sciences: naturalist Johann Gmelin, then professor of history and geography Gerard Miller, later the famous historiographer, and finally professor of astronomy Louis Delisle de la Croyer; His assistants were students A.D. Krasilnikov, later a member of the Academy of Sciences, and Popov. Gmelin and Miller were subsequently replaced by Steller and I. Fisher. The study of Kamchatka was carried out by student Stepan Krasheninnikov, later an academician. Academicians received a salary of 1,260 rubles per year, and in addition, 40 pounds of flour annually. Each academician had 4 ministers. Students were entitled to a salary of 100 rubles per year, and 30 poods of flour. Hired blacksmiths and carpenters were paid 4 kopecks a day.

Gerard Friedrich (or in Russian Fedor Ivanovich) Miller was born in 1705 in Hereford, Germany. As a twenty-year-old youth, he was invited to serve at the St. Petersburg Academy with the rank of student. In 1733 he was assigned to the Bering expedition, in which he arrived, together with Gmelin, for 10 years. In Siberia, Miller worked in archives, making extracts from papers related to the history and geography of the region. In addition, he studied the life of the Buryats, Tungus, Ostyaks, and Voguls. Since the Siberian archives then mostly burned down, the materials collected by Miller represent a priceless treasure. Some of the documents were published in the Collection of State Charters and Treaties (1819 - 1828), Additions to Historical Acts in Monuments of Siberian History, in the 2nd edition of Miller's History of Siberia and in other places.

Chapter 2. Bering's voyage to the shores of America

Seven years have already passed since the expedition left St. Petersburg, and Bering has not yet set sail. The Admiralty Board constantly confronted Bering with the slowness of the matter and in January 1737 even deprived him of his extra salary. The departure of the expedition was hampered by mutual bickering among the commanding officers. (Fig. 2) As a result of quarrels, Chirikov and Bering asked for resignation. At the beginning of 1740, Chirikov made the following offer to Bereng: he would go on a brigantine<<Михаил>> on a voyage to inspect the places lying from Kamchatka between the north and the donkey, against the Chukotka nose, and other western sides of America; by autumn Chirikov hoped to return to Okhotsk. But Bering did not agree to this, saying that such a project goes against the instructions given to him.

In June 1740, in Okhotsk, two packet boats were completed and launched, each 80 feet long, two-masted, lifting 6,000 pounds. Each had 14 small cannons. In the summer we came to Okhotsk de la Croyer and Steller. Only on September 8th the ships could go to sea. The packet boat was commanded by Bering himself. In mid-September the ships arrived in Bolsheretsk. Leaving de la Croyer and Steller here, we went from here to Avachinskaya Bay. Here, back in the summer, navigator Ivan Elagin built five residential buildings, three barracks and three barns. Bering (Fig. 3) arrived here on October 6. Since it was late, we had to spend the winter. On October 6, Bering named the harbor at the wintering site, one of the best in the world, Petropavlovskaya. October 6, 1741 should be considered the founding day of the city of Petropavlovsk. On April 18, 1741, Bering sent to his office a detailed report on the actions of the 2nd Kamchatka Expedition: this report bears the signatures of Bering, Chirikov, Chikhachev, Vaksel, Plautin and Khitrov. The package with the report was received in St. Petersburg almost a year later, after the death of the head of the expedition.

On May 1741, Bering, before his speech, convened a council at which the issue of the plan for the upcoming voyage, which had the goal of finding the shores of America, was to be decided. The manual included the ill-fated map of Delisle, on which the fantastic Land of Gama was plotted, the existence of which had already been refuted by the voyage of Spanberg in 1739. Despite the conviction of all members of the expedition that new lands should be sought east of Kamchatka, it was decided to go from Petropavlovsk to the northwest to a latitude of 46 degrees and, if the sought-after land of Gama was not there, then from here to the east. Subsequently, Bering's satellites attributed all the failures to these incorrectly chosen courses. At the same council, it was decided, when they reached land (obviously America), to go along it north to 65 degrees, and then turn west and see Chukotka land. We expected to return at the end of September.

In June 1741, the packet boats "St. Apostle Peter" under the leadership of Bering and "St. Apostle Paul" under the command of Chirikov set off for the shores of America. Bering tried to find the notorious “land of da Gama,” and Chirikov wanted to prove that America was not very far from the eastern corner of Chukotka. Commander Bering vainly ironed the Pacific Ocean in a vain attempt to find the lost land. She didn’t exist then, and she hasn’t appeared now. Storms tossed the ships... Bering's patience was running out (the patience of the crew, presumably, ended much earlier). And he gave the order to turn northeast... On June 20, in heavy fog, the ships lost each other. Next, they had to complete the task separately.

July Chirikov and his “Holy Apostle Paul” reached a land off the coast of America, now bearing the name of the first ruler of Russian settlements in America - the land of Baranov. Two days later, having sent a boat with a dozen sailors to land under the command of navigator Dementyev and not waiting for their return within a week, he sends a second one with four sailors to search for his comrades. Without waiting for the return of the second boat and not being able to approach the shore, Chirikov gave the order to continue sailing.

"Saint Apostle Paul" visited some of the islands of the Aleutian chain. From the report of A.I. Chirikov (Fig. 4) about the voyage to the shores of America. 1741, December 7: “And in the land where we walked and examined about 400 miles, we saw whales, sea lions, walruses, pigs, birds... a lot of them... On this land there are high mountains everywhere and the shores to the sea are steep. .. and on the mountains near the place where they came to the land, as shown above, the forest was quite large... Our shore turned out to be on the western side, 200 fathoms away... They came to us in 7 small leather trays, each with one person... And in the afternoon... they came to our ship in the same 14 trays, one person at a time."

After visiting the islands of the Aleutian ridge, "St. Apostle Paul" headed for Kamchatka and on October 12, 1741, arrived at Peter and Paul Harbor. The packet boat "St. Apostle Peter" was looking for "St. Apostle Paul" from the very first day of their separation. Bering had no idea that he was located next to a chain of islands that Chirikov had already visited. The arguments of Georg Steller, who observed the sea of gulls in the sea, that there should be land nearby and that it was necessary to turn north had no effect on the captain-commander, who was preoccupied with the disappearance of the ship, and even on the contrary, irritated the experienced 60-year-old Bering. The commander wandered for another two months in the hope of finding “St. Apostle Paul.” But it seemed that failure was following him. "Earth da Gama" was never found, the ship was lost... It was impossible to delay any further - the entire expedition was in jeopardy... And on July 14, naval master Sofron Khitrovo, after a long meeting, made the entry necessary for these cases in the ship's log: " And before we left the harbor, on the designated course south-east-shadow-east, we sailed not only up to 46, but also up to 45 degrees, but we didn’t see any land... For this reason, they decided to change one point, keep closer to the north, that is, to go east-north-east..."

The loss of hopes of finding the “land da Gama” and Chirikov’s ship were not the only reasons that forced the commander to change course - out of 102 barrels of water, only half remained; he had to return to Petropavlovsk no later than the end of September if the coast of America was found. But he was not there... On July 14, the packet boat "St. Peter the Apostle" went to the northern latitudes, and a day later Steller saw the outlines of the earth.

In the morning, with clear weather, all doubts disappeared. But due to weak winds, the packet boat was able to approach the shore only on July 20. This was the American northwest. Several sailors, officer Sofron Khitrovo and naturalist Steller set foot on the long-awaited shore.

“It is easy for anyone to imagine how great the joy of everyone was when we finally saw the shore; congratulations poured in from all sides to the captain, who was most responsible for the honor of the discovery,” wrote Steller, excited by the event. Only Bering did not share the general rejoicing - he was already ill. The burden of responsibility for the expedition, failures at the very beginning of the journey - all this greatly depressed Vitus Bering. Everyone rejoiced at the sheer success, the glimpses of future glory, but it was also necessary to return. Only wise with long experience of navigation, elderly, striving for this goal for 9 years, and finally having received it, Bering realized this: Who knows whether the trade winds will delay us here? The coast is unfamiliar to us; we don’t have enough food to survive the winter.

According to the instructions of the Admiralty Board, it was necessary to search for American shores and islands with extreme diligence and diligence, ... to visit them and truly discover what kind of people are on them, and what the place is called, and whether those shores are truly American. Bering could not be denied diligence, but he probably faced a difficult choice: to carry it through to the end. discoverer's cross and explore the land found with such difficulty or not risk the expedition and immediately go back with the illusory hope of returning here with third expedition ... Later researchers will often reproach Bering for indecisiveness, but extensive life experience, according to the testimony of the same Steller (who had a very strained relationship with the commander from the very beginning of the expedition) proved that Bering was more prudent than all his officers.

Already on July 20, looking at the top of Mount St. Elijah, the captain-commander probably decided to follow another part of the instructions, which said: “If time does not allow you to inspect and describe in one summer, then report in detail on that path , and without waiting for the decree, follow and finally bring it to another summer...” And having made this decision, he was already adamant, ordering to stay just as long as necessary to replenish water supplies. Bering did everything he could for Russia; he had no right to risk people’s lives anymore. I could not spend precious time on cartographic research, searching for European cities and studying the life of the aborigines.

But, probably, the general spirit of the expedition turned out to be so strong that fate was again favorable: the captain-commander was forced to yield to the pressure of the young scientist in his desire to explore the “newly invented land” and allowed Steller to join the group of sailors who were supposed to go ashore to replenish water reserves. Naturalist Steller found himself in time trouble. And you can’t call it anything other than the will of providence - what Bering achieved in 9 years, Steller managed to do in 10 hours. The observations he made, together with the data of the navigators, allowed him to draw an unmistakable conclusion - the shore of America had been found. While the team was preparing water, Steller was doing the job for which he was born into this world - he was researching.

Having come across a well-trodden path, he literally rushed headlong in search of people. The Cossack Foma Lepekhin who was accompanying him tried to hold him back: “They’ll pile on you like a gang, you won’t be able to fight back. Look, how it was cut down (about an alder twig). It must have been with a knife or an ax. Let’s go to our own people. After all, they’ll kill you here, or they’ll take you completely. We’ll be lost.” To which Steller reasonably replied: “Fool. There are people here, we need to find them...” Perseverance was partially rewarded - they came across an aboriginal fireplace and Steller was ready to swear that this was a Kamchadal camp, and if not for the landscape and vegetation he could I would still swear. Another mystery awaited him when he came across a pit similar to those in which the Kamchadals fermented fish: four steps along, three across - two human heights. But... there was no smell of fish rot. With the risk that they would be discovered sooner or later, Steller went down into the pit - it turned out to be an underground barn, in which there were birch bark vessels two cubits high, filled with smoked salmon, in others - pure sweet grass, piles of nettles, bundles of pine bark, ropes. made of sea grass of extraordinary strength, arrows that were longer than Kamchatka ones (well planed and painted black). Regarding them, Lepekhin remarked: “It’s no different than Tatar or Tunguska.” They walked another three miles in the hope of meeting residents, until they saw a stream of smoke. But they never managed to get to this fire - on the way, Steller saw a flock of birds, the breed of which he could not determine. Therefore, he asked Lepekhin to shoot one of them. At the sound of the shot, a human scream was heard from the side where they were shooting. Steller rushed there, but there was no one there, although the grass was crushed, as if someone was standing there. Probably one of the locals accompanied them all the time or, in extreme cases, just came across them and watched the uninvited guests in bewilderment. The shot scared him. This shot brought two more results - the shot bird turned out to be previously unknown to science and its discoverer was he - Georg Steller, and also the sound of this shot came to the sailor sent in search of them - it was time to return ... But in this short time he managed to collect 160 species of local plants, take samples of household utensils, get acquainted with abandoned dwellings. The very next day, on another island of the Aleutian ridge, the expedition came across American Indians.

The return journey, as Bering had expected, was difficult. Fogs and storms made it difficult for ships to move. Water and provisions were running out. Scurvy plagued people. On November 4, the expedition encountered unknown land. On November 7, Bering ordered the landing. Then no one could have imagined that they were several days' journey from Kamchatka. The difficult time of winter has come. On December 8, 1741, the leader of the expedition, Captain-Commander Vitus Jonassen Bering, died. Command passed to Lieutenant Sven Waxel. People were losing strength. Of the 76 people who landed on the island, 45 survived. Everyone who could stand on their feet hunted sea animals and birds and strengthened the crumbling dugouts.

From the report of Lieutenant S. Vaksel from the Admiralty Board on the voyage with V. Bering to the shores of America. 1742, November 15:

“This island, on which my crew and I spent the winter... is about 130 versts long, 10 versts across. There is no housing on it, but there were no signs that people had ever been on it... When we were on On this island we lived in very poor conditions, since our dwellings were in holes dug in the sand and covered with sails. And in collecting firewood we had an extreme burden, for we were forced to look for and collect firewood along the seashore and carry it on our shoulders with straps for 10 and 12 versts.

They were possessed by a severe scurvy disease... And in the spring, as those animals, out of fear, moved far from us, then they ate sea cats, which for a time in the spring sail to that island... they hunted sea cows, which are of a considerable size, for One cow will contain at least 200 pounds of meat."

Among them were Russians, Danes, Swedes, Germans - and they all fought to complete the expedition with dignity. Georg Steller found something to his liking here too - during his stay on the island, which later received the name Bering, he described 220 species of plants, observed fur seals and sea lions. His great merit was the description of the sea cow - an animal from the order of sirens, which was subsequently completely exterminated and remained only in Steller’s description. Having survived a difficult winter, the crew built a small boat from the remains of the St. Apostle Peter, broken by a storm, on which they returned to Peter and Paul Harbor on August 26, 1742. This completed the second Kamchatka expedition.

In 1743, the Senate suspended the work of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. The results of both expeditions were significant: the American coast was discovered, the strait between Asia and America was explored, the Kuril Islands, the coast of America, the Aleutian Islands were studied, and ideas about the Sea of Okhotsk, Kamchatka, and Japan were clarified.

Kamchatka expedition America

Conclusion

The Second Kamchatka Expedition was a grandiose enterprise even on a modern scale. Her work covered all of Siberia, right up to Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands, Japan, and America. The result of the expedition was: discoveries of northwestern America, description of Kamchatka by S.P. Krasheninnikov and G. Steller, works by I.G. Gmelin on the study of Siberia, extremely important materials on the historical geography of Siberia, collected by G.F. Miller, and, finally, a completely exceptional feat in the history of geographical discoveries - the description of the northern coast of Siberia.

List of used literature

1.Berg L.S., History of Russian geographical discoveries / L.S. Berg. - M., 1962. - 266 p.

.Berg L.S., Discovery of Kamchatka and the Bering expedition/ L.S. Berg - M.-L. 1946. pp. 119, 187, 220

.Sokolov A., Northern expedition of 1733-43//p. 190-469 with maps

.Route of the second Kamchatka expedition-

.The main routes of the northern detachments of the Second Kamchatka Expedition - [Appendix 2]

.Bering Vitus (Ivan Ivanovich, 1680 -1741)

.Alexey Ilyich Chirikov-

Tutoring

Need help studying a topic?

Our specialists will advise or provide tutoring services on topics that interest you.

Submit your application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.