Syntactic features of N.V. Gogol "Dead Souls"

Nikolay Gogol

DEAD SOULS

Poem

VOLUME ONE

Chapter one

At the gates of the hotel in the provincial city of NN, a rather beautiful spring small chaise drove into which bachelors travel: retired lieutenant colonels, staff captains, landowners who have about a hundred souls of peasants - in a word, all those who are called gentlemen of the middle hand. In the chaise sat a gentleman, not handsome, but not bad-looking, neither too fat nor too thin; one cannot say that he is old, but not so that he is too young. His entry did not make any noise in the city and was not accompanied by anything special; only two Russian peasants, standing at the door of the tavern opposite the hotel, made some remarks, which, incidentally, were more related to the carriage than to the one sitting in it. “You see,” one said to the other, “what a wheel! what do you think that wheel will reach, if it happened, to Moscow or not? " - "It will get there," answered the other. "And I think it won't get to Kazan?" “It won't get to Kazan,” another answered. That was the end of the conversation. Moreover, when the chaise drove up to the hotel, a young man in white rosin trousers, very narrow and short, in a tailcoat with attempts at fashion, met from under which one could see the shirt-front, fastened with a Tula pin with a bronze pistol. The young man turned back, looked at the carriage, held his cap with his hand, which almost flew off from the wind, and went his own way.

When the carriage drove into the courtyard, the master was greeted by a tavern servant, or sex, as they are called in Russian taverns, alive and agile to such an extent that it was impossible to even see what his face was. He ran out nimbly, with a napkin in his hand, all long and in a long demicotone frock coat with a back almost at the back of his head, shook his hair and led the gentleman nimbly up the entire wooden gallery to show him the peace sent to him by God. The peace was of a certain kind, for the hotel was also of a certain kind, that is, exactly the same as there are hotels in provincial cities, where for two rubles a day those passing through receive a quiet room with cockroaches looking out like prunes from all corners, and a door to the neighboring a room, always filled with a chest of drawers, where a neighbor settles, a silent and calm person, but extremely curious, interested in knowing about all the details of a passing person. The outer facade of the hotel corresponded to its interior: it was very long, two stories high; the lower one was not chiseled and remained in dark red bricks, darkened even more from the dashing weather changes and already dirty in themselves; the top one was painted with eternal yellow paint; below there were benches with clamps, ropes and steering wheels. In the coal one of these shops, or, better, in the window, there was a knock-down man with a samovar made of red copper and a face as red as a samovar, so that from a distance one might think that there were two samovars on the window, if one samovar was not with with a jet-black beard.

While the visiting gentleman was examining his room, his belongings were brought in: first of all, a suitcase made of white leather, somewhat worn out, showing that it was not the first time on the road. The suitcase was brought in by the coachman Selifan, a short man in a sheepskin coat, and a footman Petrushka, a small man of about thirty, in a spacious second-hand coat, as seen from a master's shoulder, a small, a little stern-looking fellow, with very large lips and a nose. After the suitcase was brought in a small mahogany chest with piece sets of Karelian birch, shoe stocks and fried chicken wrapped in blue paper. When all this had been brought in, the coachman Selifan went to the stable to fiddle around the horses, and the footman Petrushka began to settle down in a small front hall, a very dark kennel, where he had already managed to bring his greatcoat and with it some of his own scent, which was communicated and brought followed by a bag of various servants' toilets. In this kennel he fixed a narrow three-legged bed against the wall, covering it with a small mattress-like, dead and flat as a pancake, and perhaps as oily as a pancake, which he managed to demand from the innkeeper.

While the servants were managing and busy, the master went to the common room. What these common halls are - every passing traveler knows very well: the same walls, painted with oil paint, darkened at the top from pipe smoke and glazed from below with the backs of different passers-by, and even more native merchants, for merchants on trading days came here on their own -sem to drink their famous pair of tea; the same smoky ceiling; the same smoked chandelier with a lot of hanging pieces of glass that jumped and jingled every time the chandelier ran over the worn oilcloths, waving briskly a tray on which sat the same abyss of tea cups as birds on the seashore; the same pictures on the whole wall, painted with oil paints - in a word, everything is the same as everywhere else; the only difference is that one picture depicts a nymph with such huge breasts that the reader has probably never seen. A similar play of nature, however, happens in various historical paintings, it is not known at what time, from where and by whom they brought them to Russia, sometimes even by our nobles, art lovers, who bought them in Italy on the advice of the couriers who carried them. The gentleman took off his cap and unwound from his neck a woolen, rainbow-colored kerchief, which a married man prepares with his own hands his spouse, supplying decent instructions on how to wrap himself up, and to a single one - I probably cannot say who does, God knows them, I have never worn such kerchiefs ... Unwinding his kerchief, the gentleman ordered dinner to be served for himself. In the meantime, he was served various dishes common in taverns, such as: cabbage soup with a puff pastry, deliberately saved for passing by for several weeks, brains with peas, sausages with cabbage, fried poulard, pickled cucumber and an eternal flaky sweet pie, always ready to serve ; while all this was being served to him, both warmed up and simply cold, he made the servant, or the man, tell all sorts of nonsense - about who kept the tavern and who now, and how much income gives, and whether their owner is a big scoundrel; to which the sexual one, as usual, replied: "Oh, great, sir, a swindler." Both in enlightened Europe and in enlightened Russia there are now a lot of respectable people who, without that, cannot eat in a tavern, so as not to talk to a servant, and sometimes even make fun of him. However, the newcomer did not do all the empty questions; he asked with extreme accuracy who was the governor, who was the chairman of the chamber, who was the prosecutor — in a word, he did not miss a single significant official; but with even greater accuracy, if not even with sympathy, he asked about all the significant landowners: how many peasants have souls, how far they live from the city, what kind of character and how often they come to the city; asked carefully about the state of the region: were there any diseases in their province - general fever, murderous fevers of any kind, smallpox and the like, and everything in such detail and with such accuracy that showed more than one simple curiosity. In his receptions, the master had something solid and was blowing his nose extremely loudly. It is not known how he did it, but only his nose sounded like a trumpet. This, in my opinion, a completely innocent dignity acquired, however, he had a lot of respect from the tavern servant, so that whenever he heard this sound, he shook his hair, straightened up more respectfully and, bending his head down from the height, asked: no need or what? After dinner, the gentleman had a cup of coffee and sat down on the sofa, placing a pillow behind his back, which in Russian taverns, instead of elastic wool, is stuffed with something extremely similar to brick and cobblestone. Then he began to yawn and ordered to be taken to his room, where, lying down, he fell asleep for two hours. Having rested, he wrote on a piece of paper, at the request of the tavern servant, the rank, name and surname to report where to go, to the police. On a piece of paper, going downstairs, I read the following in the warehouses: "Collegiate councilor Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov, landowner, according to his needs." When the man was still sorting the note through the warehouses, Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov himself went to see the city, which, as it seemed, was satisfied, for he found that the city was in no way inferior to other provincial cities: the yellow paint on the stone houses was strong in the eyes and the gray darkened modestly. on wooden. The houses were of one, two and one and a half floors, with a perpetual mezzanine, very beautiful, in the opinion of the provincial architects. In places these houses seemed lost among the wide, like a field, streets and endless wooden fences; in places they huddled together, and here there was noticeable more movement of the people and liveliness. There were signs almost washed away by the rain with pretzels and boots, here and there painted blue trousers and the signature of some Arshavsky tailor; where is the store with caps, caps and the inscription: "Foreigner Vasily Fedorov"; where a billiards table was drawn with two players in tailcoats, in which the guests at our theaters who enter the stage in the last act are dressed. The players were depicted with aiming cues, arms slightly twisted back and slanting legs, having just made an antrash in the air. Under it all was written: "And here is the institution." In some places, just on the street, there were tables with nuts, soap and gingerbreads that looked like soap; where is a tavern with a painted fat fish and a fork stuck in it. Most often, the darkened two-headed state eagles were noticeable, which have now been replaced by a laconic inscription: "Drinking House". The pavement was not good everywhere. He also looked into the city garden, which consisted of slender trees, ill-used, with props below, in the form of triangles, very beautifully painted with green oil paint. However, although these trees were no taller than reeds, it was said about them in the newspapers when describing the illumination that "our city was adorned, thanks to the care of a civilian ruler, with a garden consisting of shady, wide-branching trees that give coolness on a hot day," this "it was very touching to see how the hearts of citizens trembled in excess of gratitude and shed streams of tears in token of gratitude to the mayor." Having asked in detail the security officer, where you can go closer, if necessary, to the cathedral, to public places, to the governor, he went to look at the river flowing in the middle of the city, on the way tore off the poster nailed to the post, so that when he came home, he could read it well, looked intently at a lady of not bad appearance who was walking along the wooden sidewalk, followed by a boy in military livery, with a bundle in his hand, and, once again looking at everything, as if in order to remember well the position of the place, went home straight to his room, supported lightly on the stairs by a tavern servant. After eating tea, he sat down in front of the table, ordered to bring himself a candle, took a poster out of his pocket, brought it to the candle and began to read, squinting his right eye a little. However, there was little remarkable in the poster: the drama of Mr. Kotzebue was given, in which Roll was played by Mr. Poplvin, Koru was the maiden Zyablova, other faces were even less remarkable; however, he read them all, even got to the parterre price and found out that the poster was printed in the printing house of the provincial government, then turned it over to the other side: to find out if there was something there, but, not finding anything, he rubbed his eyes, turned neatly and put it in his little chest, where he used to put everything that came across. The day, it seems, was concluded with a portion of cold veal, a bottle of sour cabbage soup and sound sleep in the whole pumping package, as they say in other parts of the vast Russian state.

The whole next day was devoted to visits; the newcomer went to make visits to all the city dignitaries. He respected the governor, who, as it turned out, like Chichikov, was neither fat nor thin, had Anna around his neck, and it was even said that he was presented to the star; however, he was a great kind-hearted man and sometimes even embroidered on tulle himself. Then he went to the vice-governor, then he was with the prosecutor, with the chairman of the chamber, with the police chief, with the tax farmer, with the head of state factories ... it is a pity that it is somewhat difficult to remember all the mighty of this world; but suffice it to say that the visitor had an extraordinary activity regarding the visits: he even came to pay his respects to the inspector of the medical board and the city architect. And then he sat in the chaise for a long time, thinking about who else to pay the visit to, and there were no more officials in the city. In conversations with these rulers, he very skillfully knew how to flatter everyone. He hinted to the governor, somehow in passing, that you enter his province like into paradise, the roads are velvet everywhere, and that those governments that appoint wise dignitaries are worthy of great praise. He said something very flattering to the police chief about the city booths; and in conversations with the vice-governor and the chairman of the chamber, who were still only state councilors, he even said twice with a mistake: “Your Excellency,” which they liked very much. The consequence of this was that the governor invited him to invite him to a house party that same day, and other officials, too, for their part, some for lunch, some for a boston, some for a cup of tea.

The newcomer seemed to avoid talking a lot about himself; if he spoke, then in some common places, with noticeable modesty, and his conversation in such cases took a somewhat bookish turn: that he was an insignificant worm of this world and was not worthy to be cared for much, that he had experienced a lot in his lifetime, endured in the service for the truth, had many enemies who even attempted on his life, and that now, wanting to calm down, he is looking to finally choose a place to live, and that, having arrived in this city, he considered it an indispensable duty to pay homage to its first dignitaries. Here is everything that the city learned about this new face, who very soon did not fail to show himself at the governor's party. It took more than two hours to prepare for this party, and here the visitor turned out to be such attentiveness to the toilet, which is not even seen everywhere. After a short afternoon nap, he ordered them to wash and rubbed both cheeks with soap for an extremely long time, propping them up from the inside with his tongue; then, taking a towel from the shoulder of the tavern servant, he wiped his full face with it from all sides, starting from behind his ears and snorting twice into the face of the tavern servant. Then he put on a shirt front in front of the mirror, plucked out two hairs that had come out of his nose, and immediately after that he found himself in a lingonberry tailcoat with a spark. Having dressed in this way, he rolled in his own carriage along the endlessly wide streets, illuminated by the skinny illumination of the ocean that flashed here and there. However, the governor's house was so illuminated, even if only for a ball; a carriage with lanterns, in front of the entrance there are two gendarmes, posters shouts in the distance - in a word, everything is as it should be. Entering the hall, Chichikov had to close his eyes for a minute, because the sparkle from candles, lamps and ladies' dresses was terrible. Everything was flooded with light. Black tailcoats flashed and ran apart and in heaps here and there, as flies scamper on white shining refined sugar in the hot July summer, when an old housekeeper chops and divides it into sparkling fragments in front of an open window; children all look, gathered around, following curiously the movements of her rigid hands, raising the hammer, and air squadrons of flies, lifted by light air, fly in boldly, like complete masters, and, taking advantage of the old woman's blindness and the sun that bothers her eyes, sprinkle tidbits where randomly, where in dense heaps Saturated with a rich summer, and already at every step arranging tasty dishes, they flew in not at all to eat, but just to show themselves, to walk back and forth on the sugar heap, rub the back or front legs, or scratch them under your wings, or, stretching out both front legs, rub them over your head, turn around and fly away again, and again fly in with new boring squadrons. Before Chichikov had time to look around, he was already seized by the arm of the governor, who introduced him to the governor at once. The visiting guest did not drop himself even here: he said some kind of compliment, very decent for a middle-aged man who has a rank not too high and not too low. When the established pairs of dancers pressed everyone against the wall, he, with his arms folded back, looked at them for two minutes very attentively. Many ladies were well dressed and in fashion, others dressed in what God sent to the provincial town. The men here, as elsewhere, were of two kinds: one slender, who all curled around the ladies; some of them were of this kind that it was difficult to distinguish them from the Petersburg ones, they also had very deliberately and tastefully combed sideburns or just specious, very clean-shaven ovals of faces, just as casually sat down to the ladies, they also spoke French and they made the ladies laugh just as in Petersburg. Another kind of men were fat or the same as Chichikov, that is, not so that too fat, but not thin either. These, on the contrary, looked sideways and backed away from the ladies and looked only around to see if the governor's servant had placed a green table for whist wherever. Their faces were full and round, some even had warts, some were pockmarked, they did not wear hair on their heads either in crests, or curls, or in the manner of “damn it,” as the French say, - they have hair were either cropped low or slicked, and the facial features were more rounded and strong. They were honorary officials in the city. Alas! the fat ones know how to manage their affairs better in this world than the thin ones. The slender ones serve more on special assignments or are only registered and waggle to and fro; their existence is somehow too easy, airy and completely unreliable. The fat ones never take indirect places, but all the straight ones, and if they sit down somewhere, they will sit down securely and firmly, so that the place will sooner crackle and creep under them, and they will not fly off. They do not like external shine; the tailcoat on them is not so cleverly cut as on the thin ones, but the grace of God is in the caskets. At three years old, a thin one does not have a single soul that is not laid in a pawnshop; at the fat man it was calm, lo and behold - and somewhere at the end of the city a house, bought in the name of his wife, appeared, then at the other end another house, then a village near the city, then a village with all the land. Finally, the fat man, having served God and the sovereign, having earned universal respect, leaves the service, moves over and becomes a landowner, a glorious Russian master, hospitable person, and lives and lives well. And after him, again, thin heirs, according to Russian custom, send all the father's goods to courier. It cannot be hidden that almost this kind of reflections occupied Chichikov at the time when he considered society, and the consequence of this was that he finally joined the fat ones, where he met almost all familiar faces: a prosecutor with very black thick eyebrows and a slightly winking left eye as if he were saying: “Come, brother, to another room, there I’ll tell you something,” - a man, however, serious and silent; the postmaster, a short man, but a wit and a philosopher; the chairman of the chamber, a very reasonable and amiable person - who all greeted him as an old acquaintance, to which Chichikov bowed a little to one side, however, not without pleasantness. He immediately met a very courteous and courteous landowner, Manilov, and a somewhat awkward-looking Sobakevich, who stepped on his foot the first time, saying: "I beg your pardon." There and then a card for whist was stuck into him, which he accepted with the same polite bow. They sat down at the green table and did not get up until dinner. All conversations have completely ceased, as always happens when they finally indulge in a meaningful occupation. Although the postmaster was very articulate, he, taking the cards in his hands, immediately expressed a thinking physiognomy on his face, covered his upper lip with his lower lip and maintained this position throughout the game. Coming out of the figure, he hit the table firmly with his hand, saying, if there was a lady: "Come on, old priest!", If the king: "Come on, Tambov man!" And the chairman would say: “And I have his mustache! And I have her mustache! " Sometimes, when the cards hit the table, the expressions burst out: “Ah! was not, no reason, so with a tambourine! " Or simply exclamations: “worms! worm-hole! pickency! " or: “pickendras! pichurushuh! pichura! " and even simply: "pichuk!" - the names with which they crossed the suits in their society. At the end of the game, they argued, as usual, quite loudly. Our guest also argued, but somehow extremely skillfully, so that everyone saw that he was arguing, and meanwhile he argued pleasantly. He never said: “you went,” but: “you deigned to go,” “I had the honor to cover your deuce,” and the like. In order to even more agree in something with his opponents, he each time brought them all his silver snuffbox with enamel, at the bottom of which they noticed two violets put there for smell. The attention of the visitor was especially taken by the landowners Manilov and Sobakevich, which were mentioned above. He at once inquired about them, and immediately called the chairman and the postmaster aside. Several questions, made by him, showed not only curiosity, but also thoroughness; for first of all he asked how many souls of peasants each of them had and what position their estates were in, and then he asked what the name and patronymic were. In a short time he completely managed to charm them. The landowner Manilov, still not at all an old man, had eyes as sweet as sugar, and who screwed them up every time he laughed, was out of his mind. He shook his hand for a very long time and asked convincingly to do him the honor of his arrival in the village, which, according to him, was only fifteen miles from the city outpost. To which Chichikov, with a very polite bowing of his head and a sincere shake of the hand, replied that he was not only ready to do it with great eagerness, but even considered it a sacred duty. Sobakevich also said somewhat laconically: "And I ask you to come to me," shuffling his foot, wearing a boot of such a gigantic size, for which one can hardly find a suitable leg, especially at the present time, when heroes are beginning to breed in Russia.

The next day Chichikov went to dinner and in the evening to the police chief, where from three in the afternoon they sat down in whist and played until two in the morning. There, by the way, he met the landowner Nozdrev, a man of about thirty, a broken-hearted fellow who, after three or four words, began to say "you" to him. With the police chief and the prosecutor, Nozdryov was also on good terms and treated in a friendly manner; but when they sat down to play the big game, the police chief and the prosecutor examined his bribes extremely carefully and watched almost every card with which he walked. The next day Chichikov spent an evening with the chairman of the chamber, who received his guests in a somewhat oiled robe, including some two ladies. Then he was at an evening with the vice-governor, at a big dinner at the tax farmer's, at a small dinner at the prosecutor's, which, however, was worth a lot; an after-mass snack given by the mayor, which was also worth dinner. In a word, he did not have to stay at home for a single hour, and he came to the hotel only to fall asleep. The newcomer somehow knew how to find himself in everything and showed himself an experienced socialite. Whatever the conversation was about, he always knew how to support him: whether it was about a horse factory, he also talked about a horse factory; whether they talked about good dogs, and here he reported very sensible remarks; whether they interpreted the investigation carried out by the treasury chamber - he showed that he was also not unaware of the judicial tricks; was there any reasoning about the billiard game - and in the billiard game he did not miss; whether they talked about virtue, and about virtue he reasoned very well, even with tears in his eyes; about making hot wine, and in hot wine he knew the good; about customs overseers and officials, and about them he judged as if he himself were both an official and an overseer. But it is remarkable that he knew how to clothe all this with some kind of degree, knew how to behave well. He spoke neither loudly nor softly, but exactly as he should. In short, wherever you turn, he was a very decent person. All officials were pleased with the arrival of the new person. The governor said about him that he was a well-meaning person; the prosecutor - that he is an efficient person; the gendarme colonel said that he was a learned man; the chairman of the chamber - that he is a knowledgeable and respectable person; the police chief - that he is a respectable and kind person; the wife of the police chief - that he is the most amiable and courteous person. Even Sobakevich himself, who rarely spoke of someone with a good side, arrived quite late from the city and already completely undressed and lay down on the bed next to his thin wife, told her: “I, darling, was at the governor’s evening, and at the police’s dined, and met the collegiate adviser Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov: a pleasant man! "To which the wife replied:" Hm! "- and pushed him with her foot.

Such an opinion, very flattering for the guest, was formed about him in the city, and it was held until then, as long as one strange characteristic of the guest and enterprise, or, as they say in the provinces, a passage about which the reader will soon find out, did not lead to complete bewilderment almost the whole city.

Chapter two

For more than a week, the visiting gentleman lived in the city, driving around parties and dinners and thus spending, as they say, a very pleasant time. Finally he decided to postpone his visits out of town and visit the landowners Manilov and Sobakevich, to whom he gave his word. Perhaps, this was prompted by another, more significant reason, a matter more serious, close to his heart ... But the reader will learn about all this gradually and in due time, if only he has the patience to read the proposed story, a very long one, which afterwards has to expand wider and more spacious as we approach the end that crowns the business. The coachman Selifan was ordered early in the morning to put the horses in the famous chaise; Petrushka was ordered to stay at home, to look after the room and the suitcase. It will not be superfluous for the reader to get acquainted with these two serfs of our hero. Although, of course, they are not so noticeable faces, and what are called secondary or even tertiary, although the main moves and springs of the poem are not approved on them and perhaps touch and easily hook them in some places, but the author loves to be extremely detailed in everything and on this side, despite the fact that the person himself is Russian, he wants to be accurate, like a German. This will take, however, not much time and space, because not much needs to be added to what the reader already knows, that is, that Petrushka wore a somewhat wide brown coat from the shoulder of the master and had, as usual, people of his rank, a large nose and lips. ... His character was more silent than talkative; he even had a noble impulse to enlightenment, that is, to read books, the content of which did not bother him: he did not care at all whether the adventures of a hero in love, just a primer or a prayer book, he read everything with equal attention; if he had been given chemotherapy, he would not have given up on it either. He liked not what he was reading about, but more the reading itself, or, better to say, the process of reading itself, that some word always comes out of the letters, which sometimes the devil knows what it means. This reading was performed more in a recumbent position in the hallway, on the bed and on a mattress, which had become as a result of such a circumstance dead and thin, like a flat cake. In addition to the passion for reading, he had two more habits, which made up two of his other characteristic features: to sleep without undressing, as it is, in the same coat, and to always carry with him some kind of his own special air, his own smell, which echoed somewhat living quarters, so that it was enough for him only to attach his bed somewhere, even in a hitherto uninhabited room, and to drag an overcoat and belongings there, and it already seemed that people had lived in this room for ten years. Chichikov, being a very delicate person and even in some cases fastidious, pulling the air towards him on a fresh nose in the morning, only grimaced and shook his head, saying: “You, brother, the devil knows you, are you sweating or something. You should even go to the bathhouse. " To which Petrushka did not answer and tried to get down to business at once; or approached with a whip to the hanging master's tailcoat, or simply tidied up something. What he thought at the time when he was silent - maybe he said to himself: "And you, however, are good, you are not tired of repeating the same thing forty times," God knows, it is difficult to know what the courtyard thinks a serf man while the master gives him instructions. So, here's what can be said for the first time about Petrushka. The coachman Selifan was a completely different person ... But the author is very ashamed to occupy his readers with people of the lower class for so long, knowing from experience how reluctant they are to get acquainted with the lower classes. Such is already a Russian person: a strong passion to conceal himself with someone who at least one rank was his higher, and a nodding acquaintance with a count or a prince for him is better than any close friendship. The author even fears for his hero, who is only a collegiate advisor. Court advisers, perhaps, will get to know him, but those who have already approached the ranks of generals, those, God knows, may even throw one of those contemptuous glances that proudly throw a man at everything that creeps at his feet. , or, even worse, perhaps, will pass by a lethal inattention for the author. But no matter how regrettable one and the other, all, nevertheless, must return to the hero. So, having given the necessary orders in the evening, waking up very early in the morning, washing himself, wiping himself from head to toe with a wet sponge, which was done only on Sundays, and on that day it happened Sunday, shaving in such a way that his cheeks became a real satin in reasoning smoothness and gloss, putting on a lingonberry-colored tailcoat with a spark and then an overcoat on big bears, he came down the stairs, supported by the arm from one side or the other by a tavern servant, and sat down in the chaise. A chaise rode out from under the gates of the hotel into the street with a thunderclap. A priest who was passing by took off his hat, several boys in soiled shirts stretched out their hands, saying: "Master, give it to the orphan!" The coachman, noticing that one of them was a big hunter to stand on the heels, whipped him with a whip, and the chaise went to jump over the stones. It was not without joy that a striped barrier was seen in the distance, which made it known that the pavement, like any other flour, would soon be over; and a few more times hitting his head quite hard on the back, Chichikov finally rushed along the soft ground. No sooner had the city gone back than they had already gone to write, according to our custom, nonsense and game on both sides of the road: bumps, spruce trees, low liquid bushes of young pines, burnt trunks of old ones, wild heather and the like.

1.1.2. How does the portrait presented in the fragment characterize the hero?

1.2.2. How do the natural world and the human world compare in Pushkin's "Tucha"?

Read the fragment of the work below and complete tasks 1.1.1-1.1.2.

At the gates of the hotel of the provincial city of NN, a rather beautiful spring small chaise drove into which bachelors travel: retired lieutenant colonels, staff captains, landowners who have about a hundred souls of peasants, & nbsp - in a word, all those who are called gentlemen of the middle hand. In the chaise sat a gentleman, not handsome, but not bad-looking, neither too fat nor too thin; one cannot say that he is old, but not so that he is too young. His entry did not make any noise in the city and was not accompanied by anything special; only two Russian peasants, standing at the door of the tavern opposite the hotel, made some remarks, which, incidentally, were more related to the carriage than to the one sitting in it. “You see, & nbsp- said one to the other, & nbsp- what a wheel! what do you think that wheel will reach, if it happened, to Moscow or not? " “And in Kazan, I think, will not reach?” & Nbsp- “It will not reach Kazan,” & nbsp- answered another. That was the end of the conversation. Moreover, when the chaise drove up to the hotel, a young man in white rosin trousers, very narrow and short, in a tailcoat with attempts at fashion, met from under which one could see the shirt-front, fastened with a Tula pin with a bronze pistol. The young man turned back, looked at the carriage, held his cap with his hand, which almost flew off from the wind, and went his own way.

When the carriage drove into the courtyard, the master was greeted by a tavern servant, or sex, as they are called in Russian taverns, alive and agile to such an extent that it was impossible to even see what his face was. He ran out nimbly, napkin in hand, all long and in a long demicotone frock coat with a back almost at the back of his head, shook his hair and quickly led the gentleman up the entire wooden gallery to show the peace that God had sent him. The peace was of a certain kind, for the hotel was also of a certain kind, that is, exactly the same as there are hotels in provincial cities, where for two rubles a day those passing through receive a quiet room with cockroaches looking out like prunes from all corners, and a door to the neighboring a room, always filled with a chest of drawers, where a neighbor settles, a silent and calm person, but extremely curious, interested in knowing all the details of a passing person. The outer facade of the hotel corresponded to its interior: it was very long, two stories high; the lower one was not plastered and remained in dark red bricks, darkened even more from the dashing weather changes and already dirty in themselves; the top one was painted with eternal yellow paint; below there were benches with clamps, ropes and steering wheels. In the coal one of these shops, or, better, in the window, there was a knock-down man with a samovar made of red copper and a face as red as a samovar, so that from a distance one might think that there were two samovars on the window, if one samovar was not with with a jet-black beard.

While the visiting gentleman was examining his room, his belongings were brought in: first of all, a suitcase made of white leather, somewhat worn out, showing that it was not the first time on the road. The suitcase was brought in by the coachman Selifan, a short man in a sheepskin coat, and a footman Petrushka, a young man of about thirty, in a spacious second-hand coat, as seen from a master's shoulder, a small man, a little stern in appearance, with very large lips and a nose. After the suitcase was brought in a small mahogany chest with piece sets of Karelian birch, shoe stocks and fried chicken wrapped in blue paper. When all this was brought in, the coachman Selifan went to the stable to fiddle around the horses, and the footman Petrushka began to settle in a small front hall, a very dark kennel, where he had already managed to bring his greatcoat and with it some of his own scent, which was communicated and brought followed by a bag of various servants' toilets. In this kennel he fixed a narrow three-legged bed against the wall, covering it with a small mattress-like, dead and flat as a pancake, and perhaps as oily as a pancake, which he managed to demand from the innkeeper.

N. V. Gogol "Dead Souls"

Read the work below and complete tasks 1.2.1-1.2.2.

A. S. Pushkin

1.1.1. Why does the city that Chichikov comes to has no name?

1.2.1. Describe the mood of the lyric hero of the poem by Alexander Pushkin.

Explanation.

1.1.1. The poem "Dead Souls" is a complex work in which merciless satire and the author's philosophical reflections on the fate of Russia and its people are intertwined. The life of the provincial town is shown in the perception of Chichikov and the author's lyrical digressions. Bribery, embezzlement and robbery of the population are constant and widespread phenomena in the city. Since these phenomena are typical for hundreds of other cities in Russia, the city in "Dead Souls" has no name. The poem presents a typical provincial town.

1.2.1. The cloud in Pushkin's poem is an unwelcome guest for the poet. He rejoices that the storm has passed and that the sky has become azure again. Only this belated cloud reminds of the past bad weather: "You alone bring a dull shadow, You alone sadden a joyous day."

Quite recently, she gave orders in heaven, because she was needed, - the cloud fed the "greedy earth" with rain. But her time has passed: “The time has passed, the Earth has refreshed, and the storm has rushed ...” And the wind drives this already unwanted guest from the enlightened heavens: “And the wind, caressing the leaves of the tree, drives You from the calm heavens”.

Thus, the cloud for the hero Pushkin is the personification of something formidable and unpleasant, terrible, perhaps some kind of misfortune. He understands that her appearance is inevitable, but he waits for her to pass, and everything will work out again. For the hero, the poem is a natural state of calm, serenity, harmony.

Explanation.

1.1.2. “In the chaise sat a gentleman, not handsome, but not bad-looking, neither too fat nor too thin; one cannot say that he is old, but not so that he is too young, "- this is how Gogol characterizes his hero already on the first pages of the poem. The portrait of Chichikov is too vague to form any first impression of him. We can only say with certainty that the person to whom he belongs is secretive, “on his own mind,” that he is driven by secret aspirations and motives.

1.2.2. The cloud in Pushkin's poem is an unwanted guest for the poet, the personification of something formidable and unpleasant, terrible, perhaps some kind of misfortune. He understands that her appearance is inevitable, but he waits for her to pass, and everything will work out again. For the hero, the poem is a natural state of calm, serenity, harmony. That is why he is glad that the thunderstorm has passed and that the sky has become azure again. Quite recently, she gave orders in heaven, because she was needed, - the cloud fed the "greedy earth" with rain. But her time has passed: “The time has passed, the Earth has refreshed, and the storm has rushed ...” And the wind drives this already unwanted guest from the enlightened heavens: “And the wind, caressing the leaves of the tree, drives You from the calm heavens”.

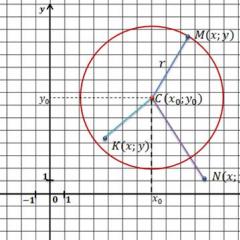

Complicated is called difficult sentence, parts of which are connected by subordinate unions or relative (union) words. The subordinate connection between parts of a complex sentence is expressed in the syntactic dependence of one part on another.

The subordinate relationship is expressed in certain formal indicators - subordinate unions and relative (union) words. Parts of a complex sentence are in semantic and structural interdependence, interconnection. And, although the formal indicator of subordination indicating the need for another part of the sentence is in the subordinate part, the main one, in turn, does not always have sufficient independence, since for one reason or another it requires a subordinate part, i.e. structurally assumes it. The interconnectedness of the parts is manifested in the semantic and structural incompleteness of the main part, in the presence of correlative words in it, as well as in the second part of the double alliance, in special forms predicate.

Separate types clauses include a significant number of varieties differing in their structure, which have their own shades in meaning and the choice of which is determined by the goals of the author. Most often, these differences depend on the use of different conjunctions and relative words, which, in addition to their inherent meanings, sometimes differ in connection with individual styles of language. Explanatory sentences reveal the object of action of the main sentence, they have an immeasurably greater capacity, having ample opportunities for transmitting a wide variety of messages. In the complex structures noted in the poem by N.V. Gogol's "Dead Souls", there are both explanatory-object clauses and other clauses semantic types. Syntactic link in polynomial complex sentences is diverse: sequential subordination and different kinds subordination. Observations show that the relationship of consistent submission is somewhat more common.

Chichikov thanked the hostess, saying that he didn’t need anything so that she didn’t worry about anything, that he didn’t demand anything except bed, and was curious only to know what places he had stopped in and how far was the way to the landowner Sobakevich from here? that the old woman said that she had never heard such a name and that there was no such landowner at all.

All the way he was silent, only whipping with a whip and did not make any instructive speech to the horses, although the forelock horse, of course, would like to hear something instructive, for at this time the reins were always somehow lazily held in the hands of the talkative driver and the whip just for the form I walked over my backs.

Without the girl, it would have been difficult to do this, too, because the roads were spreading in all directions, like caught crayfish when they are poured out of a sack, and Selifan would have had to knock over through no fault of his own.

He sent Selifan to look for the gate, which, no doubt, would have gone on for a long time if in Russia there were no dashing dogs instead of the doorman, who reported him so loudly that he raised his fingers to his ears.

Is it just so great the abyss separating her from her sister, unattainably fenced off by the walls of an aristocratic house with fragrant cast-iron stairs, shining copper, mahogany and carpets, yawning over an unfinished book in anticipation of an ingeniously secular visit, where she will have a field to shine with her mind and express thoughts, thoughts that occupy the city according to the laws of fashion for a whole week, thoughts not about what is happening in her house and her estates, confused and upset due to ignorance of the economic matter, but about what kind of political coup is being prepared in France, what direction it has taken fashionable Catholicism.

Characteristic syntactic feature complex sentence for N.V. Gogol's are complex sentences with a temporary clause in the first place or sentences with different kinds connection with the preposition of the subordinate clause. In the function of such a prepositive subordinate clause, the subordinate clause most often appears, as already mentioned. Such sentences may express relationships of temporal succession or simultaneity. In complex sentences with time-sequence relationships, the conjunction is regularly used when:

Moreover, when the chaise arrived at the hotel, there was a young man in white rosaceous trousers, very narrow and short, in a tailcoat with attempts at fashion, from under which one could see the shirt-front, fastened with a Tula pin with a bronze pistol.

When the crew drove into the yard, the gentleman was greeted by the tavern servant, or sex, as they are called in Russian taverns, lively and agile to such an extent that it was even impossible to see what his face was.

When it was all brought in, the coachman Selifan went to the stable to fiddle around the horses, and the footman Petrushka began to settle in a small front hall, a very dark kennel, where he had already managed to bring his greatcoat and with it some of his own scent, which was conveyed to the bag of different lackey's toilets.

When the established couples of dancers pushed everyone against the wall, he[Chichikov] With his hands folded back, he looked at them for two minutes very attentively.

In complex sentences with relations of simultaneity N.V. Gogol most often uses the union while or an outdated union in modern Russian meanwhile:

While the visiting gentleman looked around his room, his belongings were brought in: first of all, a suitcase made of white leather, somewhat worn out, showing that it was not the first time on the road.

For the time being, the servants were guided and fiddled, the gentleman went to the common room.

In the meantime, he was served various dishes common in taverns, such as: cabbage soup with a puff pastry, deliberately saved for passing by for several weeks, brains with peas, sausages with cabbage, fried poulard, pickled cucumber and an eternal flaky sweet pie, always ready to serve (1); while all this was served to him, both warmed up and simply cold(2) he made the servant, or the sexual one, tell all sorts of nonsense - about who kept the inn before and who now, and whether he gives a lot of income, and whether their owner is a great scoundrel; to which the sexual one, as usual, replied: "Oh, great, sir, a swindler."

When the gentoo was still picking up the note, Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov himself went to see the city, with which he seemed satisfied, for he found that the city was in no way inferior to other provincial cities: the yellow paint on the stone houses was strong in the eyes and the gray on the wooden houses modestly darkened.

The clauses of time only occasionally express a simple indication of the time of the action or event of the main part. This usually happens when, in the subordinate clause, indications are given of the attitude to certain phenomena that serve to determine the time (morning, day; spring, summer; minute, hour, year, century, etc.). In the vast majority of cases, temporary sentences represent the ratio in time of two statements, and subordinate part is not limited to a simple designation of time, but concludes a special message, one way or another related to the message of the main sentence.

An infinitive construction can act as a subordinate part of a complex sentence; such a subordinate clause is especially closely related to main part... If in the subordinate part of the goal is used conditional mood, then it is more semantically independent, independently:

To even more agree on something with their opponents, every time he brought them all his silver snuffbox with enamel, at the bottom of which they noticed two violets put there for smell.

In the poem by N.V. Gogol's "Dead Souls" there are complex sentences with repeating parts that have the same meaning and the same conjunctions. For example, sentences with the same type of clauses. In assignment clauses, the union is often used although; it should also be noted that they are regularly prepositive in a complex sentence:

Although, of course, they are not so noticeable faces, and what are called minor or even tertiary, although the main passages and springs of the poem are not approved on them and only touch and easily hook them in some places- but the author loves to be extremely thorough in everything and from this side, despite the fact that the person himself is Russian, wants to be accurate, like a German.

Although the postmaster was very articulate, but he, taking the cards in his hands, immediately expressed a thinking physiognomy on his face, covered his upper lip with his lower lip and kept this position throughout the game.

Although the time during which they will pass through the vestibule, the front hall and the dining room is somewhat short, but let's try to see if we can somehow use it and say something about the owner of the house.

No matter how sedate and reasonable he was, but here he almost even made a leap like a goat, which, as you know, is made only in the strongest outbursts of joy.

Offensive sentences indicate a condition that is an obstacle to the performance of the action of the main part, or enclosed in a subordinate clause that contradicts the message of the main part; they, firstly, establish an opposition between the messages of the subordinate clause and the main clause (and in this they are similar to adversary sentences), and secondly, they indicate that the obstructing condition or the contradictory message of the subordinate clause is not so significant as to interfere with the implementation of the action of the main part or interfere with the message given in it. Concessive sentences are a kind of contrast to conditional sentences: both indicate conditions, but the first ones are obstructive, and the second ones facilitate the implementation of an action or phenomenon of the main part, while concessive sentences usually indicate real existing conditions, while conditional sentences predominantly on the expected conditions.

Conceivable sentences are on the verge of submission and composition, in them in the main part opposing conjunctions are often used but, however, and.

Indicate the type of complex sentences with several subordinate clauses (I. С homogeneous subordination; II. With heterogeneous subordination; III. With consistent submission. IV. WITH different types subordination of several subordinate clauses Make diagrams and determine the types of clauses.

- 1. Should a hero not be here when there is a place where he can turn around and walk? 2. But when they brought him to the final death throes, it seemed as if his strength began to succumb. 3. When the carriage entered the courtyard, the master was greeted by a tavern servant or sex, as they are called in Russian taverns, alive and agile to such an extent that it was impossible to even see what his face was. 4. Approaching the courtyard, Chichikov noticed on the porch the owner himself, who was standing in a green shalon coat with his hand to his forehead in the form of an umbrella over his eyes in order to get a better look at the approaching carriage. 5. He [Chichikov] sent Selifan to look for the gate, which, no doubt, would have gone on for a long time, if in Russia there were no dashing dogs instead of doormen, who reported him so loudly that he raised his fingers to his ears. 6. Then our Cherevik himself noticed that he was overheated, and in an instant he covered his head with his hands, assuming without a doubt that the angry concubine would not hesitate to grab his hair with her conjugal claws. 7. The guests congratulated both Bulba and both young men and told them that they were doing a good deed and that there was no better science for young man like the Zaporizhzhya Sich. (From the works of Y. Gogol.)

- Although for the first time in his life he had to shoot a man point-blank with a revolver and this might not have shaken him to the depths of his incredible, maddening simplicity, yet he did not experience anything even remotely similar to remorse. 5. As soon as Gavrik ran up Pirogovskaya Street from the direction of the hospital to the entrance of the headquarters, already surrounded on all sides by his detachment, he saw that he was late. 6. Gavrik and Sinichkin approached the car and learned that this was a delegation of the ship committees "Sinop", "Rostislav" and "Almaz", which was delivering an ultimatum to the command of the Central Rada troops with a decisive demand to stop hostilities and withdraw the Haidamak units to their barracks. (From the works of V. Kataev.)