Berg is a scientist in biology. Berg, Lev Semyonovich

Source - Wikipedia

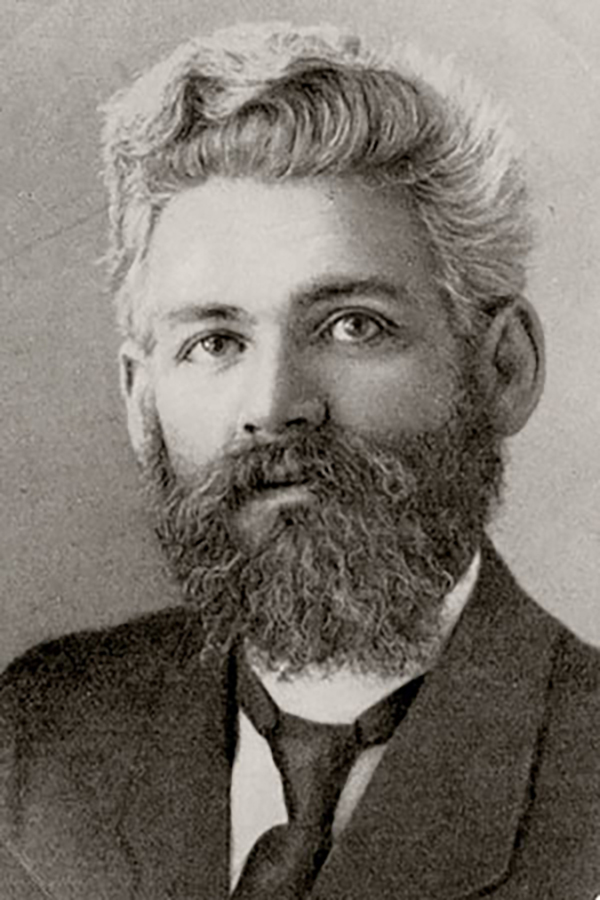

Lev Semyonovich Berg

Date of birth: 14 (26) March 1876

Place of birth: Bendery, Bendery district, Bessarabian province, Russian Empire

Died: December 24, 1950 (age 74)

Place of death: Leningrad

Country: Russian Empire> USSR

Scientific field: ichthyology, evolutionism

Academic title: Academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences

Alma mater: Imperial Moscow University

Notable students: A. G. Isachenko

Physical geographer and biologist, academician, president Geographical Society USSR (since 1940). He developed the theory of landscapes, was the first to carry out zonal physical and geographical zoning of the USSR. In 1922 he put forward the evolutionary concept of nomogenesis.

Awards and prizes

Order of the Red Banner of Labor

Medal "For the Defense of Leningrad"

Medal "For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945 "

Stalin Prize - 1951

Constantine medal

Researcher who described a number of zoological taxa. For attribution, the names of these taxa are accompanied by the designation "Berg".

Lev Semenovich (Simonovich) Berg (March 14 (26), 1876 - December 24, 1950) - Russian and Soviet zoologist and geographer.

Corresponding member (1928) and full member (1946) of the USSR Academy of Sciences, president of the Geographical Society of the USSR (1940-1950), laureate of the Stalin Prize (1951 - posthumously). Author of fundamental works on ichthyology, geography, theory of evolution.

Born in Bendery into a Jewish family. His father, Simon G. Berg, was a notary; mother, Klara Lvovna Bernstein-Kogan, was a housewife. They lived in a house on Moskovskaya Street.

The first wife of L. S. Berg (in 1911-1913) - Paulina Adolfovna Katlovker (March 27, 1881-1943), the younger sister of the famous publisher B. A. Katlovker. Children - geographer Simon Lvovich Berg (October 23, 1912, St. Petersburg - November 17, 1970) and geneticist, writer, doctor of biological sciences Raisa Lvovna Berg (March 27, 1913 - March 1, 2006). In 1922, L. S. Berg remarried a teacher of Petrograd pedagogical institute Maria Mikhailovna Ivanova.

In 1921-1950. Berg occupied a residential service wing of the former palace of Alexei Alexandrovich (Leningrad, Prospect Maklin, 2).

He died on December 24, 1950 in Leningrad. He was buried at Literatorskie mostki at the Volkovskoye cemetery.

Education and scientific career [edit | edit source]

1885-1894 - studied at the second Chisinau gymnasium, which he graduated with a gold medal. In 1894 he was baptized into Lutheranism to obtain the right to higher education within the Russian Empire.

1894-1899 - student of the Natural Sciences Department of the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of the Imperial Moscow University. (His thesis was on fish embryology and was awarded a gold medal)

1899-1902 - superintendent of fisheries in the Aral Sea and Syrdarya.

1903-1904 - superintendent of fisheries in the middle reaches of the Volga.

1905-1913 - Head of the Fish Department of the Zoological Museum of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

1913-1914 - Acting Professor of Ichthyology and Hydrology at the Moscow Agricultural Institute.

1916-1950 - as a professor of geography, he headed the department of geography at Petrograd and then Leningrad University.

1918-1925 - Professor of Geography at the Geographical Institute in Petrograd (Leningrad).

1932-1934 - Head of the Department of Applied Ichthyology at the Institute of Fisheries.

1934-1950 - head of the department in the laboratory of ichthyology of the Zoological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in Leningrad.

1948-1950 - Chairman of the Ichthyological Commission of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Since 1934 - Doctor of Zoology.

Since 1928 - Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Since 1946 - a full member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

Contribution to science

The scientific heritage of Lev Semyonovich Berg is very significant.

As a geographer, having collected extensive materials on the nature of different regions, he made generalizations on the climatic zonality of the globe, a description of the landscape zones of the USSR and neighboring countries, and created the textbook "The Nature of the USSR". Berg, the creator of modern physical geography, is the founder of landscape science, and the landscape division proposed by him, although supplemented, has survived to this day.

Berg is the author of the soil theory of loess formation. His works made a significant contribution to hydrology, lakes, geomorphology, glaciology, desert studies, the study of surface sedimentary rocks, questions of geology, soil science, ethnography, paleoclimatology.

Berg is a classic of world ichthyology. He described the fish fauna of many rivers and lakes, proposed "systems of fish and fish-like living and fossils." He is the author of the major work "Fish fresh water USSR and neighboring countries ”.

Berg's contribution to the history of science is significant. This topic is the subject of his books about the discovery of Kamchatka, V. Bering's expedition, E. Bykhanov's theory of continental drift, the history of Russian discoveries in Antarctica, the activities of the Russian Geographical Society, etc.

Berg is the author of the book "Nomogenesis, or Evolution Based on Regularities" (1922), in which he proclaimed his anti-Darwinian concept of evolution. Such scientists as A. A. Lyubishchev and S. V. Meyen considered themselves to be his followers. Even in our time, that is, a hundred years later, his concept has its adherents. These include, for example, V.V. Ivanov, a Soviet linguist, semioticist, anthropologist, academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences (2000).

Awards, prizes and honorary titles

1909 - Gold medal of P.P.Semenov-Tyan-Shansky for work on the Aral Sea from the Russian Geographical Society (RGO).

1915 - Konstantinovskaya medal from the Russian Geographical Society, was elected an honorary member of MOIP.

1934 - Honored Scientist of the RSFSR.

1936 - Gold Medal of the Asian Society of India for Zoological Research in Asia.

1945 - Order of the Red Banner of Labor and medal "For the Defense of Leningrad"

1946 - Order of the Red Banner of Labor in connection with the 70th birthday anniversary and the medal "For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945."

1951 - Stalin Prize I degree for the work "Fish of fresh waters of the USSR and neighboring countries" (posthumously).

Major works

Only the most basic works are listed here. For a complete bibliography, see the book by V.M.Raspopova.

1918. Bessarabia. Country. People. Household. - Petrograd: Lights, 1918 .-- 244 p. (the book contains 30 photographs and a map)

1905. Fish of Turkestan. Izv. Turk. dep. Russian Geographical Society, v. 4.16 + 261 p.

1908. Aral Sea: Experience of a physical-geographical monograph. Izv. Turk. dep. Russian Geographical Society, v.5. 9.24 + 580 s.

1912. Fish (Marsipobranchii and Pisces). Fauna of Russia and neighboring countries. T. 3, no. 1. SPb. 336 s.

1914. Fish (Marsipobranchii and Pisces). Fauna of Russia and neighboring countries. T. 3, no. 2. Pg. S. 337-704.

1916. Freshwater Fish Russian Empire... M. 28 + 563 p.

1922. Climate and Life. M. 196 p.

1922. Berg LS Nomogenesis, or Evolution Based on Regularities. - Petersburg: State Publishing House, 1922 .-- 306 p.

1929. Berg L.S.Essays on the history of Russian geographical science(up to 1923). - L .: Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, State. a type. them. Eug. Sokolova, 1929 .-- 152, p. - (Proceedings of the Commission on the History of Knowledge / Academy of Sciences of the USSR; 4). - 1,000 copies

1931. Landscape-geographical zones of the USSR. M.-L .: Selkhozgiz. Part 1.401 p.

1940. "The System of Fish and Fish, Living and Fossilized." In the book. Tr. Zool. Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the SSR, vol. 5, no. 2.S. 85-517.

1946. Discovery of Kamchatka and Bering's expedition. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. (M.-L., 1946. preface by the author - from January 1942, circulation 5000, 379 p.)

1946. Essays on the history of Russians geographical discoveries... (M. - L., 1946, 2nd ed. 1949).

1947. Berg LS Lomonosov and the hypothesis of moving continents // News of the All-Union Geographical Society. - M .: Publishing house of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1947. - T. No. 1. - P. 91-92. - 2000 copies.

1977. (posthumously). Works on the theory of evolution, 1922-1930. L. 387 p.

Memory

Named after L. S. Berg: a volcano on the Urup island, a peak in the Pamirs, a cape on the island October revolution(Severnaya Zemlya), glaciers in the Pamirs and Dzhungarskiy Alatau. His name was included in the Latin names of more than 60 animals and plants.

On February 28, 1996, in Bendery, one of the streets of the city's microdistrict - Borisovka - was named after Berg.

Lev Semenovich Berg

Geographer, ichthyologist, climatologist.

“... It was an unusually backward county town,” Berg recalled, “there were no pavements, and by autumn all the streets were covered with a layer of liquid mud, which could only be walked on in special super-deep galoshes, which I have never seen since; apparently they were specially made for the needs of the inhabitants of Bendery. There was no street lighting in the city, and on dark autumn nights you had to wander the streets with a hand lamp. Of the middle educational institutions there was one gymnasium, for some reason female. Obviously, no newspapers were published in the city ”.

Only the gold medal with which Berg graduated from the Chisinau gymnasium allowed him to enter Moscow University.

Lectures by outstanding scientists D. N. Anuchin, A. P. Bogdanov, V. I. Vernadsky, M. A. Menzbir, K. A. Timiryazev helped Berg to define his scientific interests early. Anthropologist and ethnographer D. N. Anuchin and geologist A. P. Pavlov had a particular influence on him.

Berg graduated from the university in 1898.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to get a job in Moscow in any scientific or educational institution. Only the recommendation of Academician Anuchin helped Berg to get a job as supervisor of fisheries in the Aral Sea. Without wasting time, he left for the provincial town of Akmolinsk.

The Aral Sea was then real. The water from the Amu-Darya had not yet been taken along irrigation ditches to the desert, and the skeletons of the ships of the former fish flotilla did not stick out among the dry sands. Berg studied the huge reservoir for several years. He managed to take a new approach to explaining nature The aral sea and painted a fairly convincing picture of the development of the sea, closely related to the history of the Turan lowland and the dry channel of the Uzboy, through which some of the Amu Darya waters once went to the Caspian. In his work “The Question of Climate Change in Historical Era,” Berg refuted the prevailing notions of shrinkage at the time. Central Asia and the progressive change in its climate towards an increase in desert.

In 1909, for his work on the Aral Sea, which Berg presented as a master's thesis, he was immediately awarded a doctorate. Reviews were presented by D. N. Anuchin, V. I. Vernadsky, A. P. Pavlov, M. A. Menzbir, G. A. Kozhevnikov, V. V. Bartold and E. E. Leist time.

From 1904 to 1914, Berg was in charge of the fish and reptile department of the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. During these years he completed and published a number of excellent studies on fish in Turkestan and the Amur region.

In 1916, Berg was elected professor at Petrograd University.

The main works of this period are devoted to the origin of the fauna of Lake Baikal, the fish of Russia, the origin of loess, climate changes in the historical era and the division of the Asian territory of Russia into landscape and morphological regions.

Revolutionary events interrupted Berg's field studies for a long time.

The first major works of the scientist, published after the revolution, were "Nomogenesis, or evolution based on laws" and "Theory of Evolution" (1922). Berg wrote both of these books while sitting in an overcoat in an unheated room, heating the freezing ink on the fire of a smokehouse. In these works devoted to the theory of evolution, Berg distinguished three directions:

criticism of the main evolutionary teachings and, first of all, the Darwinian one,

development of one's own hypothesis about the causes of evolution, based on the recognition of some initial expediency and "autonomous orthogenesis" as the main law of evolution, acting centripetally and independently of the external environment, and

generalization of the laws of macroevolution, such as irreversibility, an increase in the level of organization, a long continuation of evolution in the same direction, convergence, etc.

Berg's evolutionary work was prompted by the crisis that Darwinism experienced in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Berg never shared Charles Darwin's view of the causes of evolution. He believed that variability in nature is always adaptive, and organisms do not respond gradually to changes in external conditions, but, on the contrary, abruptly, in leaps and bounds, massively. Thus, Berg attached decisive importance to variability, and not natural selection... Of course, "Nomogenesis" ("set of laws"), developed by Berg, aroused a lot of objections. Berg's assertion that there is no place for accidents in biological evolution, and everything happens naturally, sounded too defiant. But the historically indicated works of Berg turned out to be extremely important, if only because both sharply raised the problem of the direction of evolution and the role of internal factors in phylogeny, polyphilia, convergence and parallelism. The view of the majority of Berg's opponents was well expressed by Professor N. N. Plavilshchikov. “The book“ Nomogenesis ”, - he wrote, - is one of the next attempts to subvert the theory of selection. Of course, nothing worthwhile came of this attempt and could not come out, despite the author's monstrous erudition and the well-known wit of his conclusions: twice two is always four. To deny the theory of selection ... But can there be another explanation of the appropriateness in the structure of organisms? ... "

This, however, can be answered with the words of Herbert Spencer: humanity goes straight, only after exhausting all possible crooked paths.

As a natural scientist, Berg always strove to give his arguments the form of strictly empirical constructions. "To find out the mechanism of the formation of adaptations is the task of the theory of evolution," he wrote. As for living matter, Berg generally believed that it is conceivable only as an organism. “The dreams of those chemists who thought that by producing protein synthesis in a flask, they would receive a 'living substance' are naive. There is no living matter at all, there are living organisms. "

“Darwin's theory aims to explain mechanically the origin of expediency in organisms,” he wrote in his work The Theory of Evolution. - We consider the ability to make expedient reactions to be the main property of the organism. It is not an evolutionary doctrine that has to figure out the origin of expediency, but the discipline that undertakes to argue about the origin of living things. This question, in our opinion, is a metaphysical one. Life, will, soul, absolute truth - all these are transcendental things, knowledge of the essence of which science is not able to give. Where and how life came from, we do not know, but it is carried out on the basis of laws, like everything that happens in nature. Transmutation, whether it takes place in the sphere of dead or living nature, takes place according to the laws of mechanics, physics and chemistry. IN the world is dead matter is dominated by the principle of randomness, that is, large numbers. Here the most probable things come true. But what is the principle underlying the organism, in which the parts are subordinated to the whole, we do not know. Likewise, we do not know why organisms in general increase in their structure, that is, they progress. How this process is happening, we begin to understand, but why- to this science can now answer as little as in 1790, when Kant expressed his famous prophecy. "

Under pressure from criticism of his views on evolution, Berg returned to questions of geography and ichthyology. One after another appeared his books "The Population of Bessarabia" (1923), "The Discovery of Kamchatka and Kamchatka expeditions Bering "(1924)," Foundations of climatology "(1927)," Essays on the history of Russian geographical science "(1929)," Landscape-geographical zones of the USSR "(1931)," Nature of the USSR "(1937)," System of fish-like and fish " (1940), "Climate and Life" (1947), "Essays on Physical Geography" (1949), "Russian Discoveries in Antarctica and Contemporary Interest in It" (1949).

The breadth of Berg's views can be judged by the content of his books.

Essays on physical geography, for example, include sections: "On the alleged separation of the continents", "On the alleged connection between the great glaciations and mountain building", "On the origin of the Ural bauxites", "On the origin of iron ores of the Kryvyi Rih type", "The level of the Caspian Sea for historical time "," Baikal, its nature and its origin organic world". And in the book "Essays on the History of Russian Geographical Discoveries" he concerns not only the history of these discoveries themselves, but also such, it would seem, unusual topic as "Atlantis and the Aegeid", in which he comes to a conclusion unexpected for his contemporaries. “I would place Atlantis not in the area between Asia Minor and Egypt,” he writes, “but in the Aegean Sea, south to Crete. As you know, in our time it is recognized that the subsidence, which gave rise to the Aegean Sea, occurred, geologically speaking, quite recently, in the Quaternary time - perhaps already in the memory of man. "

In 1925, Berg again visited his beloved Aral. These his studies were associated with work at the Institute of Experimental Agronomy, where Berg from 1922 to 1934 headed the Department of Applied Ichthyology.

In 1926, Berg visited Japan as part of a delegation from the USSR Academy of Sciences. He went there specially through Manchuria and Korea in order to get the most complete picture of the nature of these countries. And the following year, Berg represented Soviet science in Rome at the limnological congress.

Unbelievable hard work was the main feature of Berg. During his life, he managed to complete over nine hundred scientific works... He worked constantly, which is probably why he managed so much. In everything he observed a certain system. He was a convinced vegetarian, never smoked, went to work only on foot. His immense erudition allowed Berg to feel at home in any field of science.

“… Science leads to morality,” he wrote in his book “Science, its meaning, content and classification”, “because it, demanding proof everywhere, teaches impartiality and justice. There is nothing more alien to science than blind admiration for authorities. Science honors its spiritual leaders, but does not create idols of them. Each of these provisions can be challenged and, indeed, challenged. The motto of science is tolerance and humanity, for science is alien to fanaticism, admiration for authorities, and, therefore, despotism. The consciousness of the scientist that in his hands is the only one accessible to man objective truth that he possesses knowledge, supported by evidence, that this knowledge, as long as it is not scientifically refuted, is obligatory for everyone, all this makes him value this knowledge extremely highly, and, in the words of the poet, “... for the power, for the livery, do not bend any conscience , no thoughts, no neck. " The high moral value of science lies in the example of selflessness given by a dedicated scientist. Therefore, it is not in vain that the crowd, which strives for wealth, fame and power and for the material benefits associated with all this, looks at the scientist as an eccentric or a maniac. "

Whatever topic Berg worked on, he always tried to expand it broadly and give clear conclusions.

In this respect, the book "Fishes of the Amur River Basin" (1909) is indicative.

It would seem a narrowly zoological summary, giving a description of the fish found in the system of the Amur River. But three small chapters of this work - "The general character of the ichthyological fauna of the Amur basin", "Fish of the Amur from the point of view of zoological geography" and "The origin of the ichthyological fauna of the Amur" - are of enduring interest for geographers and naturalists. TO natural phenomena Berg fits in their complex interrelationships, paints a vivid picture of the origin of the modern landscapes of the Amur basin, attracts not only ichthyological material. Actually, identifying causal links phenomena - the main task and method of his research.

Berg's works on paleoclimatology, paleogeography, biogeography, and especially climate change in the historical period are very significant. They are all written simple language some are popular in the best possible sense of the term. For example, the book "Climate and Life" can be read and understood by anyone who is interested in the issues of climate and life. Berg's books about Russian travelers and researchers have survived a lot of editions. Working in the archives, he sometimes found absolutely remarkable facts that allowed him back in 1929 to boldly assert that “... the Russians within the limits of the USSR alone put on the map and studied an area equal to one-sixth of the land surface, that vast areas were explored in the border with Russia regions of Asia, that all the shores of Europe and Asia from Varanger Fjord to Korea, as well as the coast of a significant part of Alaska, were put on the map by Russian sailors. Let's add that many islands have been discovered and described by our sailors in the Pacific Ocean. "

Berg was widely known for his geographic work.

Mountains of Norway, deserts of Turkestan, Far East, the European part of Russia - everything was reflected in his system of views on the world. He did a tremendous job in the field of regional studies, his profound works on natural zones became the property of not only professional geographers, but also botanists and zoologists. He was one of the first to deal with the issues of scientific geographic regionalization, having done remarkable work on the regionalization of Siberia and Turkestan, Asian Russia and the Caucasus. He owns the major summary "Freshwater Fish of the USSR and Neighboring Countries." Of the 528 species of fish found in the rivers and lakes of our country, 70 species were first discovered and described by Berg. He created a scheme for dividing the whole world, separately Soviet Union and Europe into a number of zoogeographic regions based on the distribution of certain fish species. In search of ways to develop fish, Berg took up the study of fossils. And here he achieved excellent results, having written the outstanding work "System of fish-like and fish, living and fossil" (1940, 1955, Berlin, 1958).

Berg's university textbooks are in excellent living language. He always opposed the abstruse terminology, through which one must wade through, as through a thorny thicket. He even wrote a special article in which he sharply opposed such complicated terminology as, for example, "differential centrifugation of the dermal pulp of infected rabbits" or "anthropodynamic impulses." The latter, by the way, only means - the influence of man. Berg never tired of reminding the words of Lomonosov: "What we love in the style of Latin, French or German, sometimes it is worthy of laughter in Russian."

In 1904, Berg was elected a full member of the Russian Geographical Society, thirty-six years later he became its president. Academician since 1946. In 1951 he was posthumously awarded the State Prize.

Death found the scientist with a book in his hands.

This text is an introductory fragment. From the book of 100 Great Adventurers the author Muromov Igor From the book of 100 great composers the author Samin DmitryAlban Berg (1885-1935) One of the most prominent representatives of expressionism in music, Berg expressed in his work the thoughts, feelings and images characteristic of expressionist artists: dissatisfaction with social life, feelings of powerlessness and loneliness. His hero

From the book Popular History of Music the author Gorbacheva Ekaterina GennadevnaAlban Berg Austrian composer, teacher, representative of the new Viennese school Alban Berg was born in 1885. He was a student and follower of A. Schoenberg, with whom he studied in 1904 - 1910.Berg began his career in the art of music with the piano sonata opus 1 (1908) and

From the book Art Museums of Belgium the author Sedova Tatiana AlekseevnaMuseum Mayer van den Berg The charm of this private collection lies not only in the taste and character of its collector, a passionate art lover, but also in the fact that it is located in an old patrician house of the 15th century with dark oak

From the book Lexicon nonclassics. Artistic and aesthetic culture of the XX century. the author The team of authors TSBBerg Axel Ivanovich Berg Axel Ivanovich [b. 29.10 (10.11) .1893, Orenburg], Soviet radio engineer, engineer-admiral, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences (1946; corresponding member 1943), Hero of Socialist Labor (1963). Member of the CPSU since 1944. In 1914 he graduated from the Marine Corps. As navigator of a submarine

From the book Big Soviet Encyclopedia(BU) of the author TSBBerg Alban Berg Alban (9.2.1885, Vienna, - 24.12.1935, ibid.), Austrian composer. One of the most prominent representatives of expressionism in music. He studied composition under the guidance of A. Schoenberg, who had a significant influence on the formation of the creative principles of B. First

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BU) of the author TSBBerg Fedor Fedorovich Berg Fedor Fedorovich, Russian geodesist. Studied at Dorpat (now Tartu) University. In the 20s. compiled a military statistical description of Turkey. Supervised (1823, 1825) expeditions

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BU) of the author TSBBerg Eizhen Avgustovich Berg Eizhen Avgustovich (1892, Riga, - September 20, 1918), an active participant in the October Revolution of 1917 and Civil War... Member of the Communist Party since 1917. Born into a fisherman's family. During World War I he was a machinist on the battleship Sevastopol. After the February

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BU) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BU) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BU) of the author TSB From the book The most famous scientists of Russia the author Prashkevich Gennady MartovichLev Semenovich Berg Geographer, ichthyologist, climatologist. Born on March 14, 1876 in the city of Bendery (Bessarabia) into a notary's family. liquid mud, by

From book Big dictionary quotes and catch phrases the author Dushenko Konstantin VasilievichBERG, Nikolai Vasilievich (1823-1884), poet-translator, journalist, historian 213 In Holy Russia, the roosters are crowing, Soon there will be a day in Holy Russia. The authorship is presumably. The couplet is reproduced in the 2nd edition (1892) of VG Korolenko's essay "On the Eclipse". In M. Gorky's version: “On the saint

From the book Berlin. Guide author Bergmann JurgenPRENZLAUER BERG C? Fe Anita Wronski, Knaackstr. 26-28. The pub opens early. Senefelderplatz underground station on line U2. Kommandantur Knaackstra? E / corner Rykestra? E. Hippie Italian restaurant. Senefelderplatz underground station on line U2. Restauration 1900, Husemannstr. 1. Fried pork legs and brisket, as well as vegetarian dishes,

From the book Field Marshals in the History of Russia the author Rubtsov Yuri ViktorovichBERG Lev Semenovich(1876-1950), physicogeographer and biologist, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences (1946). Developed the doctrine of landscapes and developed the ideas of V.V.Dokuchaev about natural areas Oh. He was the first to carry out the zonal physical and geographical division into districts of the USSR. Major works on ichthyology (anatomy, taxonomy and distribution of fish), climatology, lake science, as well as the history of geography. In 1922 he put forward the evolutionary concept of nomogenesis. President of the Geographical Society of the USSR (1940-50). USSR State Prize (1951).

BERG Lev Semenovich(Simonovich), Russian scientist-encyclopedist, zoologist, geographer, evolutionist, historian of science.

Born into a Jewish family, his father was a notary. While studying at the Chisinau gymnasium (1885-94), he was fond of natural science - he collected herbariums, dissected fish, read scientific literature... In 1894 he was baptized and entered Moscow University. As a student, he became known for his experiments in fish farming. Graduate work on pike embryology was Berg's 6th published work. After graduating from the university (1898, gold medal) he worked at the Ministry of Agriculture as an inspector of fisheries in the Aral Sea and the Volga, explored steppe lakes, rivers, deserts.

In 1902-1903 Berg studied hydrology in Bergen (Norway), in 1904-13 he worked at the Zoological Museum of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, in 1913 he moved to Moscow, where he received a professor position at the Moscow Agricultural Institute. In 1916, Berg was invited to the Department of Physical Geography of St. Petersburg University, where he worked until the end of his life.

Berg's first major scientific works were "Fish of Turkestan" (1905) and his master's thesis "The Aral Sea" (1908), for which Berg immediately received a doctorate in geography. In 1909-16, Berg published 5 monographs on fish in Russia, but his main subject was scientific interests becomes geography. He developed a theory of the origin of loess, proposed the first classification of natural zones in the Asian part of Russia. By this time, Berg's scientific style and methods of work had developed, and he was striking with extraordinary productivity (he owns over 800 works). He was distinguished by iron self-discipline, tenacious memory, the ability to work without drafts and in any conditions, clarity and clarity of presentation (the text began with the definition of concepts) and conclusions, excellent literary language.

Berg stood aloof from politics, but he was acutely worried about the horrors of war and revolution, interpreting them as a brief triumph of the principle of struggle over the principle of cooperation. Having no conditions for field work during this period, Berg expanded teaching activities(in 1916-18 - in Moscow and Petrograd in parallel) and wrote ("heating freezing ink on the fire of a smokehouse") 3 works on the theory of evolution (1922). They analyze the basic concepts (evolution, progress, expediency, chance, the emergence of a new one, simplicity of theory, directionality), the role of the struggle for existence as a factor of evolution (both in nature and in society) is rejected, the role of natural selection is sharply limited (it is only protects the norm) and put forward an original theory of evolution - nomogenesis, i.e. evolution based on laws.

The theory had a number of weaknesses, which colleagues (A. A. Lyubishchev, D. N. Sobolev, Yu. A. Filipchenko) immediately noted, but in general the criticism took on an ideological character, especially after the publication of the English edition of Nomogenesis (1926). NI, who defended Berg from persecution, wrote to him (1927): "We will not release you from your post. The ship must be guided, no matter what monsters get in the way." Berg did not write more about the mechanisms of evolution. In 1928 he was elected a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences (in 1946 - an academician) as a geographer.

In geography, Berg is known as the creator of Russian lakes science and landscape theory ("geography is the science of landscapes"). In climatology, Berg classified climates in relation to landscapes, explained desertification by human activity, and glaciation by "factors of a cosmic order." Berg denied continental drift; following VI Vernadsky, he pushed the emergence of life back to the very beginning of geological history.

In zoogeography, Berg offered his own interpretations of the distribution of fish and other aquatic animals, for example, he showed the local origin of the Baikal fauna, and, on the contrary, explained the composition of the Caspian fauna by post-glacial migration along the Volga. In ichthyology, Berg's main works are: "The system of fish-like fish and fish, living today and fossils" (1940) and the classic three-volume "Fish of fresh waters of the USSR and neighboring countries" (1949, State Prize 1951), which have retained their scientific significance to this day, as well as numerous work on breeding and fishing of fish.

Berg's interest in history and ethnography, which arose in his youth ("The Urals on the Syr Darya", 1900), has not been lost over the years. In this area, his work is devoted to the discoveries of Russians in Asia, Antarctica, Alaska (Essays on the History of Russian Geographical Discoveries, 1949), old maps, the life of small peoples (Gagauz, Laz, etc.), biographies of scientists. Thanks to Berg, many forgotten names and facts of Russian priority were restored. As an ethnographer, Berg used his knowledge of languages and zoology in his scientific work (for example, "The names of fish and ethnic relations of the Slavs", 1948).

Geographer, ichthyologist, climatologist.

“... It was an unusually backward county town,” Berg recalled, “there were no pavements, and by autumn all the streets were covered with a layer of liquid mud, which could only be walked on in special super-deep galoshes, which I have never seen since; apparently they were specially made for the needs of the inhabitants of Bendery. There was no street lighting in the city, and on dark autumn nights you had to wander the streets with a hand lamp. From secondary educational institutions there was one gymnasium, for some reason female. Obviously, no newspapers were published in the city ”.

Only the gold medal with which Berg graduated from the Chisinau gymnasium allowed him to enter Moscow University.

Lectures by outstanding scientists D. N. Anuchin, A. P. Bogdanov, V. I. Vernadsky, M. A. Menzbir, K. A. Timiryazev helped Berg to define his scientific interests early. Anthropologist and ethnographer D. N. Anuchin and geologist A. P. Pavlov had a particular influence on him.

Berg graduated from the university in 1898.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to get a job in Moscow in any scientific or educational institution. Only the recommendation of Academician Anuchin helped Berg to get a job as supervisor of fisheries in the Aral Sea. Without wasting time, he left for the provincial town of Akmolinsk.

The Aral Sea was then real. The water from the Amu-Darya had not yet been taken along irrigation ditches to the desert, and the skeletons of the ships of the former fish flotilla did not stick out among the dry sands. Berg studied the huge reservoir for several years. He managed to approach the explanation of the nature of the Aral Sea in a new way and painted a fairly convincing picture of the development of the sea, closely related to the history of the Turan lowland and the dry channel of the Uzboy, through which part of the Amu Darya waters once went to the Caspian. In his work "The Question of Climate Change in a Historical Era," Berg refuted the then widespread notions about the drying up of Central Asia and about the progressive change in its climate towards an increase in desert.

In 1909, for his work on the Aral Sea, which Berg presented as a master's thesis, he was immediately awarded a doctorate. Reviews were presented by D. N. Anuchin, V. I. Vernadsky, A. P. Pavlov, M. A. Menzbir, G. A. Kozhevnikov, V. V. Bartold and E. E. Leist time.

From 1904 to 1914, Berg was in charge of the fish and reptile department of the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. During these years he completed and published a number of excellent studies on fish in Turkestan and the Amur region.

In 1916, Berg was elected professor at Petrograd University.

The main works of this period are devoted to the origin of the fauna of Lake Baikal, the fish of Russia, the origin of loess, climate changes in the historical era and the division of the Asian territory of Russia into landscape and morphological regions.

Revolutionary events interrupted Berg's field studies for a long time.

The first major works of the scientist, published after the revolution, were "Nomogenesis, or evolution based on laws" and "Theory of Evolution" (1922). Berg wrote both of these books while sitting in an overcoat in an unheated room, heating the freezing ink on the fire of a smokehouse. In these works devoted to the theory of evolution, Berg distinguished three directions:

criticism of the main evolutionary teachings and, first of all, the Darwinian one,

development of one's own hypothesis about the causes of evolution, based on the recognition of some initial expediency and "autonomous orthogenesis" as the main law of evolution, acting centripetally and independently of the external environment, and

generalization of the laws of macroevolution, such as irreversibility, an increase in the level of organization, a long continuation of evolution in the same direction, convergence, etc.

Berg's evolutionary work was prompted by the crisis that Darwinism experienced in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Berg never shared Charles Darwin's view of the causes of evolution. He believed that variability in nature is always adaptive, and organisms do not respond gradually to changes in external conditions, but, on the contrary, abruptly, in leaps and bounds, massively. Thus, Berg attached decisive importance to variability, and not to natural selection. Of course, "Nomogenesis" ("set of laws"), developed by Berg, aroused a lot of objections. Berg's assertion that there is no place for accidents in biological evolution, and everything happens naturally, sounded too defiant. But the historically indicated works of Berg turned out to be extremely important, if only because both sharply raised the problem of the direction of evolution and the role of internal factors in phylogeny, polyphilia, convergence and parallelism. The view of the majority of Berg's opponents was well expressed by Professor N. N. Plavilshchikov. “The book“ Nomogenesis ”, - he wrote, - is one of the next attempts to subvert the theory of selection. Of course, nothing worthwhile came of this attempt and could not come out, despite the author's monstrous erudition and the well-known wit of his conclusions: twice two is always four. To deny the theory of selection ... But can there be another explanation of the appropriateness in the structure of organisms? ... "

This, however, can be answered with the words of Herbert Spencer: humanity goes straight, only after exhausting all possible crooked paths.

As a natural scientist, Berg always strove to give his arguments the form of strictly empirical constructions. "To find out the mechanism of the formation of adaptations is the task of the theory of evolution," he wrote. As for living matter, Berg generally believed that it is conceivable only as an organism. “The dreams of those chemists who thought that by producing protein synthesis in a flask, they would receive a 'living substance' are naive. There is no living matter at all, there are living organisms. "

“Darwin's theory aims to explain mechanically the origin of expediency in organisms,” he wrote in his work The Theory of Evolution. - We consider the ability to make expedient reactions to be the main property of the organism. It is not an evolutionary doctrine that has to figure out the origin of expediency, but the discipline that undertakes to argue about the origin of living things. This question, in our opinion, is a metaphysical one. Life, will, soul, absolute truth - all these are transcendental things, knowledge of the essence of which science is not able to give. Where and how life came from, we do not know, but it is carried out on the basis of laws, like everything that happens in nature. Transmutation, whether it takes place in the sphere of dead or living nature, takes place according to the laws of mechanics, physics and chemistry. In the world of dead matter, the principle of randomness prevails, that is, large numbers. Here the most probable things come true. But what is the principle underlying the organism, in which the parts are subordinated to the whole, we do not know. Likewise, we do not know why organisms in general increase in their structure, that is, they progress. How this process is happening, we begin to understand, but why- to this science can now answer as little as in 1790, when Kant expressed his famous prophecy. "

Under pressure from criticism of his views on evolution, Berg returned to questions of geography and ichthyology. One after another appeared his books "The Population of Bessarabia" (1923), "The Discovery of Kamchatka and the Kamchatka Expeditions of Bering" (1924), "Foundations of Climatology" (1927), "Essays on the History of Russian Geographical Science" (1929), "Landscape-Geographical Zones USSR "(1931)," Nature of the USSR "(1937)," System of fish-like and fish "(1940)," Climate and life "(1947)," Essays on physical geography "(1949)," Russian discoveries in Antarctica and modern interest in her ”(1949).

The breadth of Berg's views can be judged by the content of his books.

Essays on physical geography, for example, include sections: "On the alleged separation of the continents", "On the alleged connection between the great glaciations and mountain building", "On the origin of the Ural bauxites", "On the origin of iron ores of the Kryvyi Rih type", "The level of the Caspian Sea for historical time "," Baikal, its nature and the origin of its organic world. " And in the book "Essays on the History of Russian Geographical Discoveries" he touches not only on the history of these discoveries themselves, but also on such a seemingly unusual topic as "Atlantis and the Aegean", in which he comes to a conclusion unexpected for his contemporaries. “I would place Atlantis not in the area between Asia Minor and Egypt,” he writes, “but in the Aegean Sea, south to Crete. As you know, in our time it is recognized that the subsidence, which gave rise to the Aegean Sea, occurred, geologically speaking, quite recently, in the Quaternary time - perhaps already in the memory of man. "

In 1925, Berg again visited his beloved Aral. These his studies were associated with work at the Institute of Experimental Agronomy, where Berg from 1922 to 1934 headed the Department of Applied Ichthyology.

In 1926, Berg visited Japan as part of a delegation from the USSR Academy of Sciences. He went there specially through Manchuria and Korea in order to get the most complete picture of the nature of these countries. And the following year, Berg represented Soviet science in Rome at the limnological congress.

Unbelievable hard work was the main feature of Berg. During his life, he managed to complete over nine hundred scientific works. He worked constantly, which is probably why he managed so much. In everything he observed a certain system. He was a convinced vegetarian, never smoked, went to work only on foot. His immense erudition allowed Berg to feel at home in any field of science.

“… Science leads to morality,” he wrote in his book “Science, its meaning, content and classification”, “because it, demanding proof everywhere, teaches impartiality and justice. There is nothing more alien to science than blind admiration for authorities. Science honors its spiritual leaders, but does not create idols of them. Each of these provisions can be challenged and, indeed, challenged. The motto of science is tolerance and humanity, for science is alien to fanaticism, admiration for authorities, and, therefore, despotism. The consciousness of a scientist that in his hands is the only objective truth accessible to man, that he possesses knowledge, supported by evidence, that this knowledge, as long as it is not scientifically refuted, is obligatory for everyone, all this makes him value this knowledge extremely highly, and, in the words of the poet , "... for the authorities, for the livery, do not bend either conscience, or thoughts, or neck." The high moral value of science lies in the example of selflessness given by a dedicated scientist. Therefore, it is not in vain that the crowd, which strives for wealth, fame and power and for the material benefits associated with all this, looks at the scientist as an eccentric or a maniac. "

Whatever topic Berg worked on, he always tried to expand it broadly and give clear conclusions.

In this respect, the book "Fishes of the Amur River Basin" (1909) is indicative.

It would seem a narrowly zoological summary, giving a description of the fish found in the system of the Amur River. But three small chapters of this work - "The general character of the ichthyological fauna of the Amur basin", "Fish of the Amur from the point of view of zoological geography" and "The origin of the ichthyological fauna of the Amur" - are of enduring interest for geographers and naturalists. Berg approaches natural phenomena in their complex interrelationships, paints a vivid picture of the origin of the modern landscapes of the Amur basin, and attracts not only ichthyological material. Actually, identifying the causal relationships of phenomena is the main task and method of his research.

Berg's works on paleoclimatology, paleogeography, biogeography, and especially climate change in the historical period are very significant. All of them are written in simple language, some are popular in the best sense of the term. For example, the book "Climate and Life" can be read and understood by anyone who is interested in the issues of climate and life. Berg's books about Russian travelers and researchers have survived a lot of editions. Working in the archives, he sometimes found absolutely remarkable facts that allowed him back in 1929 to boldly assert that “... the Russians within the limits of the USSR alone put on the map and studied an area equal to one-sixth of the land surface, that vast areas were explored in the border with Russia regions of Asia, that all the shores of Europe and Asia from Varanger Fjord to Korea, as well as the coast of a significant part of Alaska, were put on the map by Russian sailors. Let's add that many islands have been discovered and described by our sailors in the Pacific Ocean. "

Berg was widely known for his geographic work.

The mountains of Norway, the deserts of Turkestan, the Far East, the European part of Russia - everything is reflected in his system of world views. He did a tremendous job in the field of regional studies, his profound works on natural zones became the property of not only professional geographers, but also botanists and zoologists. He was one of the first to deal with the issues of scientific geographic regionalization, having done remarkable work on the regionalization of Siberia and Turkestan, Asian Russia and the Caucasus. He owns the major summary "Freshwater Fish of the USSR and Neighboring Countries." Of the 528 species of fish found in the rivers and lakes of our country, 70 species were first discovered and described by Berg. He created a scheme for dividing the whole world, separately the Soviet Union and Europe, into a number of zoogeographic regions based on the distribution of certain species of fish. In search of ways to develop fish, Berg took up the study of fossils. And here he achieved excellent results, having written the outstanding work "System of fish-like and fish, living and fossil" (1940, 1955, Berlin, 1958).

Berg's university textbooks are in excellent living language. He always opposed the abstruse terminology, through which one must wade through, as through a thorny thicket. He even wrote a special article in which he sharply opposed such complicated terminology as, for example, "differential centrifugation of the dermal pulp of infected rabbits" or "anthropodynamic impulses." The latter, by the way, only means - the influence of man. Berg never tired of reminding the words of Lomonosov: "What we love in the style of Latin, French or German, sometimes it is worthy of laughter in Russian."

In 1904, Berg was elected a full member of the Russian Geographical Society, thirty-six years later he became its president. Academician since 1946. In 1951 he was posthumously awarded the State Prize.

Death found the scientist with a book in his hands.

G. Prashkevich

The scientific interests of Lev Semenovich Berg were unusually broad. Berg created new geography: it is difficult to name any of the physical and geographical disciplines, critical issues which did not receive a deep and original development in his works.

Lev Semenovich (Simonovich) Berg was born on March 2, 1876 in Bendery, Bessarabian province, into the family of a notary. His father, Simon G. Berg (originally from Odessa), was a notary; mother, Klara Lvovna Bernstein-Kogan, was a housewife. He had younger sisters Maria (April 18, 1878) and Sophia (December 23, 1879). The family lived in a house on Moskovskaya Street.

Already during his studies at the gymnasium (Chisinau, 1885-1894), Lev Semenovich was carried away self-study nature. In 1894, he entered Moscow University, where, in addition to his studies, he performed a series of experiments on fish breeding. The diploma work on pike embryology was the sixth published work of the young scientist. After graduation with a gold medal from the university (1898), Lev Semenovich worked in the Ministry of Agriculture as an inspector of fisheries in the Aral Sea and the Volga, investigated steppe lakes, rivers, deserts.

In 1902-1903, Lev Berg continued his education in Bergen (Norway), and then in 1904-1913 he worked at the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences. Per master's thesis"Aral Sea", prepared in 1908, L.S. Berg was awarded a doctorate.

In 1913, L.S. Berg moved to Moscow, where he received a professor position at the Moscow Agricultural Institute. In 1916, he was invited to the Department of Physical Geography at Petrograd University, where he worked until the end of his life.

In the period 1909-1916. L.C. Berg published 5 monographs on the ichthyology of water bodies in Russia, but the main subject of his scientific interests is physical geography. Lev Semenovich created a theory of the origin of loess, proposed the first classification of natural zones in the Asian part of Russia.

The outstanding Russian encyclopedic scientist owns about 1000 works in different areas earth sciences, such as climatology, biology, zoology, ichthyology, zoogeography, lakes science, evolution theory, landscape studies, geomorphology, cartography, geobotany, paleogeography, paleontology, economical geography, soil science, ethnography, linguistics, history of science. Full list works of L.S. Berg until 1952, inclusive, was published in the book “In memory of academician L.S. Berg ".

In climatology, L.S. Berg classified climates in relation to landscapes, explained desertification by human activity, and glaciation by "factors of a cosmic order." In zoogeography, Berg proposed original mechanisms for the distribution of fish and other aquatic animals. In particular, Lev Semenovich showed the local origin of the fauna of Baikal, and, on the contrary, explained the formation of the diversity of the fauna of the Caspian Sea by the migration of species along the Volga in the postglacial period.

In 1922, in the most difficult conditions of war communism, “heating up the freezing ink on the fire of the smokehouse”, L.S. Berg prepared a number of works on the theory of evolution, in which, in an elegant polemic with the conclusions of Charles Darwin, he put forward the evolutionary concept of nomogenesis (evolution based on laws). Apolitical L.S. Berg, on the basis of colossal empirical material, rejected the role of the struggle for existence as a factor of evolution, both in nature and in human society.

The theory of evolution by L.S. Berga was subjected to both constructive criticism modern scientists (A. A. Lyubishchev, D. N. Sobolev and others), and the brutal ideological pressure from the dogmatic political system, especially after the publication in 1926 of the book "Nomogenesis" in English.

January 14, 1928 L.S. Berg was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in the biological category of the Department of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, and on November 30, 1946 - Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in the Department of Geological and Geographical (specializing in zoology, geography). Historical works of L.S. Berga are devoted to a detailed description of domestic discoveries in Asia, Alaska and Antarctica, the study of ancient maps, the culture and ethnography of small peoples, and the compilation of biographical descriptions of famous scientists. L.S. Berg, on the basis of an analysis of the original documents, consistently defended the priority of Russian researchers in the discovery of Antarctica and pointed out the need for comprehensive studies of the ice continent. Ideas and historical approach L.S. Berga contributed to the development of a national position in the development of Antarctica.

In the period 1940-1950. L.S. Berg was President of the Geographical Society of the USSR.

The first wife of L. S. Berg (in 1911-1913) - Paulina Adolfovna Katlovker (March 27, 1881-1943), the younger sister of the famous publisher B. A. Katlovker. Children - geographer Simon Lvovich Berg (1912, St. Petersburg - November 17, 1970) and geneticist, writer, Doctor of Biological Sciences Raisa Lvovna Berg (March 27, 1913 - March 1, 2006). In 1922 L. S. Berg remarried the teacher of the Petrograd Pedagogical Institute Maria Mikhailovna Ivanova.

Lev Semenovich Berg died on December 24, 1950 in Leningrad and was buried at Literatorskie Mostki of the Volkovsky cemetery. In 1951, L.S. Berg was awarded the USSR State Prize (posthumously) for the classic three-volume book on ichthyology (1949).

In the name of L.S. Berg are named:

- Lev Berg Mountains (67 ° 42 ′ S, 48 ° 55 ′ E 14 miles south of Cape Buromsky, Krylov Peninsula) - mountains on the George V Coast, Victoria Land, East Antarctica. Named 1959

- Cape Berga is a cape in the North of the October Revolution Island of the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Named 1913;

- Cape Berga - a cape on the island of Georg Land, Franz Josef Land archipelago. Named in 1953;

- Berg Peak and Berg Glacier in the Pamirs;

- Berga volcano on Iturup island;

- research vessel “Akademik Berga”.

His name is included in the Latin names of more than 60 animals and plants, for example, a deep-sea stingray is named after him.

The city of Bendery is the birthplace of the Soviet scientist-encyclopedist, physical-geographer and biologist Lev Semenovich Berg. In 1959, the widow of the late scientist, Maria Mikhailovna Ivanova, came to Bender. She found and pointed out to the city authorities the house where Berg was born. At the same time, a memorial plaque appeared on the house, which is located on the street. Moscow.

On February 28, 1996, in Bendery, one of the streets of the city's microdistrict - Borisovka - was named after Berg. On February 22, 2005, the Ministry of Justice of the PMR, in the city of Bender, registered the Public Educational Fund named after M. Academician L. S. Berg. The administration and residents of the city expressed a desire to organize a museum in Berg's house, however, two families live in this house, which, for this, need to be provided with other housing. Therefore, at the moment, the question of creating a museum to them. Berga remains unresolved.